Japanese tea ceremony

In Japanese the term is Sadō or Chadō, which literaly translated means "tea way" and places the emphasis on the Tao (道).

The English term "Teaism" was coined by Okakura Kakuzō to describe the unique worldview associated with Japanese way of tea as opposed to focusing just on the presentation aspect, which came across to the first western observers as ceremonial in nature.

A chakai is a relatively simple course of hospitality that includes wagashi (confections), thin tea, and perhaps a light meal.

It is found in an entry in the Nihon Kōki having to do with the Buddhist monk Eichū (永忠), who had brought some tea back to Japan on his return from Tang China.

[9] In China, tea had already been known, according to legend, for more than three thousand years (though the earliest archaeological evidence of tea-drinking dates to the 2nd century BCE).

Its original meaning indicated quiet or sober refinement, or subdued taste "characterized by humility, restraint, simplicity, naturalism, profundity, imperfection, and asymmetry" and "emphasizes simple, unadorned objects and architectural space, and celebrates the mellow beauty that time and care impart to materials.

Sen no Rikyū and his work Southern Record, perhaps the best-known – and still revered – historical figure in tea, followed his master Takeno Jōō's concept of ichi-go ichi-e, a philosophy that each meeting should be treasured, for it can never be reproduced.

The principles he set forward – harmony (和, wa), respect (敬, kei), purity (清, sei), and tranquility (寂, jaku) – are still central to tea.

[17] Sen no Rikyū was the leading teamaster of the regent Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who greatly supported him in codifying and spreading the way of tea, also as a means of solidifying his own political power.

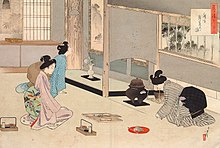

A purpose-built chashitsu typically has a low ceiling, a hearth built into the floor, an alcove for hanging scrolls and placing other decorative objects, and separate entrances for host and guests.

Jin or Byakudan are used in the summer, and during the end of spring or the beginning of autumn, the Chajin puts out Kokukobei or Umegako.

This style of sharing a bowl of koicha first appeared in historical documents in 1586, and is a method considered to have been invented by Sen no Rikyū.

A chakai may involve only the preparation and serving of thin tea (and accompanying confections), representing the more relaxed, finishing portion of a chaji.

[25] The honorary title Senke Jusshoku [ja] is given to the ten artisans that provide the utensils for the events held by the three primary iemoto Schools of Japanese tea known as the san-senke.

The following is a general description of a noon chaji held in the cool weather season at a purpose-built tea house.

The guests arrive a little before the appointed time and enter an interior waiting room, where they store unneeded items such as coats, and put on fresh tabi socks.

When all the guests have arrived and finished their preparations, they proceed to the outdoor waiting bench in the roji, where they remain until summoned by the host.

)[28] The items are treated with extreme care and reverence as they may be priceless, irreplaceable, handmade antiques, and guests often use a special brocaded cloth to handle them.

Every action in chadō – how a kettle is used, how a teacup is examined, how tea is scooped into a cup – is performed in a very specific way, and may be thought of as a procedure or technique.

This procedure originated in the Urasenke school, initially for serving non-Japanese guests who, it was thought, would be more comfortable sitting on chairs.

Except when walking, when moving about on the tatami one places one's closed fists on the mats and uses them to pull oneself forward or push backwards while maintaining a seiza position.

The lines in tatami mats (畳目, tatami-me) are used as one guide for placement, and the joins serve as a demarcation indicating where people should sit.

Calligraphic scrolls may feature well-known sayings, particularly those associated with Buddhism, poems, descriptions of famous places, or words or phrases associated with tea.

[33] Historian and author Haga Kōshirō points out that it is clear from the teachings of Sen no Rikyū recorded in the Nanpō roku that the suitability of any particular scroll for a tea gathering depends not only on the subject of the writing itself but also on the virtue of the writer.

Haga points out that Rikyū preferred to hang bokuseki ("ink traces"), the calligraphy of Zen Buddhist priests, in the tea room.

It evolved from the "free-form" style of ikebana called nageirebana (投げ入れ, "throw-in flowers"), which was used by early tea masters.

Dishes are intricately arranged and garnished, often with real edible leaves and flowers that are to help enhance the flavour of the food.

In Japan, those who wish to study tea ceremony typically join a "circle", a generic term for a group that meets regularly to participate in a given activity.

In some cases, advanced students may be given permission to wear the school's mark in place of the usual family crests on formal kimono.

The first things new students learn are how to correctly open and close sliding doors, how to walk on tatami, how to enter and exit the tea room, how to bow and to whom and when to do so, how to wash, store and care for the various equipment, how to fold the fukusa, how to ritually clean tea equipment, and how to wash and fold chakin.