Teleology in biology

Teleology in biology is the use of the language of goal-directedness in accounts of evolutionary adaptation, which some biologists and philosophers of science find problematic.

Before Darwin, organisms were seen as existing because God had designed and created them; their features such as eyes were taken by natural theology to have been made to enable them to carry out their functions, such as seeing.

Evolutionary biologists often use similar teleological formulations that invoke purpose, but these imply natural selection rather than actual goals, whether conscious or not.

Some biologists and religious thinkers held that evolution itself was somehow goal-directed (orthogenesis), and in vitalist versions, driven by a purposeful life force.

Teleology, from Greek τέλος, telos "end, purpose"[3] and -λογία, logia, "a branch of learning", was coined by the philosopher Christian von Wolff in 1728.

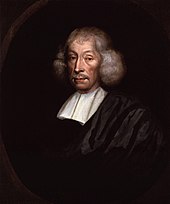

[9][10] The English parson-naturalist John Ray stated that his intention was "to illustrate the glory of God in the knowledge of the works of nature or creation".

[14] The biophysicist Pierre Lecomte du Noüy and the botanist Edmund Ware Sinnott developed vitalist evolutionary philosophies known as telefinalism and telism respectively.

Their views were heavily criticized as non-scientific;[15] the palaeontologist George Gaylord Simpson argued that Du Noüy and Sinnott were promoting religious versions of evolution.

[16] The Jesuit paleontologist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin argued that evolution was aiming for a supposed spiritual "Omega Point" in what he called "directed additivity".

[21] Natural selection, introduced in 1859 as the central mechanism[a] of evolution by Charles Darwin, is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype.

"[25] An adaptation is an observable structure or other feature of an organism (for example, an enzyme) generated by natural selection to serve its current function.

[26][28][29] Apparent teleology is a recurring issue in evolutionary biology,[30] much to the consternation of some writers,[31] and as an explanatory style it remains controversial.

[40] Statements which imply that nature has goals, for example where a species is said to do something "in order to" achieve survival, appear teleological, and therefore invalid to evolutionary biologists.

Ayala extends this type of teleological explanation to non-human animals by noting that "A deer running away from a mountain lion ... has at least the appearance of purposeful behavior.

"[49] Ayala, relying on work done by the philosopher Ernest Nagel, also rejects the idea that teleological arguments are inadmissible because they cannot be causal.

For Pittendrigh, the notion of 'adaptation' in biology, however it is defined, necessarily "connote that aura of design, purpose, or end-directedness, which has, since the time of Aristotle, seemed to characterize the living thing.

The confusion, he says, would be removed if we described these systems "by some other term, like 'teleonomic,' in order to emphasize that the recognition and description of end-directedness does not carry a commitment to Aristotelian teleology as an efficient causal principle.

"[56] Ernst Mayr criticised Pittendrigh's confusion of Aristotle's four causes, arguing that evolution only involved the material and formal but not the efficient cause.