Philosophy of mind

Modern philosophers of mind continue to ask how the subjective qualities and the intentionality of mental states and properties can be explained in naturalistic terms.

[25][26] The problems of physicalist theories of the mind have led some contemporary philosophers to assert that the traditional view of substance dualism should be defended.

[5] One of the earliest known formulations of mind–body dualism was expressed in the eastern Samkhya and Yoga schools of Hindu philosophy (c. 650 BCE), which divided the world into purusha (mind/spirit) and prakriti (material substance).

In Western philosophy, the earliest discussions of dualist ideas are in the writings of Plato who suggested that humans' intelligence (a faculty of the mind or soul) could not be identified with, or explained in terms of, their physical body.

They would almost certainly deny that the mind simply is the brain, or vice versa, finding the idea that there is just one ontological entity at play to be too mechanistic or unintelligible.

[5] Modern philosophers of mind think that these intuitions are misleading, and that critical faculties, along with empirical evidence from the sciences, should be used to examine these assumptions and determine whether there is any real basis to them.

The zombie argument is based on a thought experiment proposed by Todd Moody, and developed by David Chalmers in his book The Conscious Mind.

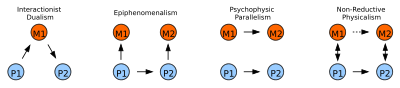

Although Leibniz was an ontological monist who believed that only one type of substance, the monad, exists in the universe, and that everything is reducible to it, he nonetheless maintained that there was an important distinction between "the mental" and "the physical" in terms of causation.

While body and mind are different substances, causes (whether mental or physical) are related to their effects by an act of God's intervention on each specific occasion.

[55] Experiential dualism notes that our subjective experience of merely seeing something in the physical world seems qualitatively different from mental processes like grief that comes from losing a loved one.

Rather, experiential dualism is to be understood as a conceptual framework that gives credence to the qualitative difference between the experience of mental and physical states.

Madhayamaka Buddhism goes further, finding fault with the monist view of physicalist philosophies of mind as well in that these generally posit matter and energy as the fundamental substance of reality.

[56] The way out, therefore, was to eliminate the idea of an interior mental life (and hence an ontologically independent mind) altogether and focus instead on the description of observable behavior.

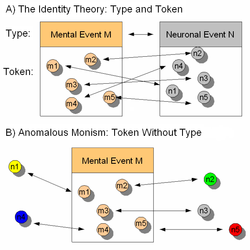

Eliminativists such as Patricia and Paul Churchland argue that while folk psychology treats cognition as fundamentally sentence-like, the non-linguistic vector/matrix model of neural network theory or connectionism will prove to be a much more accurate account of how the brain works.

The Churchlands believe the same eliminative fate awaits the "sentence-cruncher" model of the mind in which thought and behavior are the result of manipulating sentence-like states called "propositional attitudes".

The 20th-century German philosopher Martin Heidegger criticized the ontological assumptions underpinning such a reductive model, and claimed that it was impossible to make sense of experience in these terms.

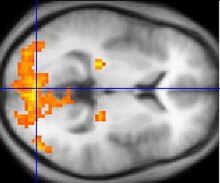

[76] This problem of explaining introspective first-person aspects of mental states and consciousness in general in terms of third-person quantitative neuroscience is called the explanatory gap.

David Chalmers and the early Frank Jackson interpret the gap as ontological in nature; that is, they maintain that qualia can never be explained by science because physicalism is false.

Patricia Churchland argues for a deep integration of neuroscience and philosophy, emphasizing that understanding the mind requires grounding philosophical questions in empirical findings about the brain.

Churchland challenges traditional dualistic and purely conceptual approaches to the mind, advocating for a materialistic framework where mental phenomena are understood as brain processes.

She posits that philosophical theories of mind must be informed by advances in neuroscience, such as the study of neural networks, brain plasticity, and the biochemical basis of cognition and behavior.

Churchland critiques the idea that introspection or purely conceptual analysis can sufficiently explain consciousness, arguing instead that empirical methods can illuminate how subjective experiences arise from neural mechanisms.

The exclusive objective of "weak AI", according to Searle, is the successful simulation of mental states, with no attempt to make computers become conscious or aware, etc.

It includes research on intelligence and behavior, especially focusing on how information is represented, processed, and transformed (in faculties such as perception, language, memory, reasoning, and emotion) within nervous systems (human or other animals) and machines (e.g. computers).

Cognitive science consists of multiple research disciplines, including psychology, artificial intelligence, philosophy, neuroscience, linguistics, anthropology, sociology, and education.

[95] It spans many levels of analysis, from low-level learning and decision mechanisms to high-level logic and planning; from neural circuitry to modular brain organization.

can globally be seen to differ from the analytic school in that they focus less on language and logical analysis alone but also take in other forms of understanding human existence and experience.

With reference specifically to the discussion of the mind, this tends to translate into attempts to grasp the concepts of thought and perceptual experience in some sense that does not merely involve the analysis of linguistic forms.

[102] Existentialism, a school of thought founded upon the work of Søren Kierkegaard, focuses on Human predicament and how people deal with the situation of being alive.

Such an idea is unacceptable to modern philosophers with physicalist orientations and their general skepticism of the concept of "self" as postulated by David Hume, who could never catch himself not doing, thinking or feeling anything.