Temnospondyli

See below Temnospondyli (from Greek τέμνειν, temnein 'to cut' and σπόνδυλος, spondylos 'vertebra') or temnospondyls is a diverse ancient order of small to giant tetrapods—often considered primitive amphibians—that flourished worldwide during the Carboniferous, Permian and Triassic periods, with fossils being found on every continent.

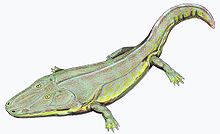

During about 210 million years of evolutionary history, they adapted to a wide range of habitats, including freshwater, terrestrial, and even coastal marine environments.

Although temnospondyls are amphibians, many had characteristics such as scales and large armour-like bony plates (osteoderms) that generally distinguish them from the modern soft-bodied lissamphibians (frogs and toads, newts, salamanders and caecilians).

In 2000, Adam Yates and Anne Warren defined the name Temnospondyli as applying to the clade encompassing all organisms that are more closely related to Eryops than to the “microsaur” Pantylus.

[1] By this definition, if lissamphibians are temnospondyls and Pantylus is a reptiliomorph, the name Temnospondyli is synonymous with Batrachomorpha (a clade containing all organisms that are more closely related to modern amphibians than to mammals and reptiles).

[9] However, there are many other possible hypotheses for the purpose of the ornamentation (e.g., increasing surface area for better adhesion of the skin to the skull),[10] and the function(s) remains largely unresolved due to the absence of this feature in lissamphibians.

[25][26][27][28][29][30] Many taxa, especially those inferred to have been terrestrial, have an opening at the midline near the tip of the snout called the internarial fenestra / fontanelle; this may have housed a mucous gland used in prey capture.

[8][31][58][59][60][61] In some temnospondyls, such as the dvinosaur Erpetosaurus, the capitosaur Mastodonsaurus and the trematosaur Microposaurus, tusks in the lower jaw pierce the palate and emerge through openings in the top of the skull.

In living tetrapods, the main body of the vertebra is a single piece of bone called the centrum, but in temnospondyls, this region was divided into a pleurocentrum and intercentrum.

[65] Additional types that are less common are the plagiosaurid-type in which there is a single enlarged centrum of uncertain homology;[66][67][68][69][70] and the tupilakosaurid-type vertebrae (diplospondyly) in which the pleurocentra and intercentra are the same size and form discs; this occurs in tupilakosaurid dvinosaurs but also at least some brachyopids and several other non-temnospondyls.

[77][78] The function of this sail, like that of the contemporaneous sphenacodontids and edaphosaurids, remains enigmatic, but it is thought to have stiffened the vertebral column in association with the relative terrestriality of this clade.

Most members of the family Dissorophidae also have armor, although it only covers the midline of the back with one or two narrow rows of plates that tightly articulated with the vertebrae,[103][104][105][106] and osteoderms are also known from a few trematopids.

The most extensive records come from fine-grained deposits in the Carboniferous and Permian of Germany; the small-bodied and aquatic dissorophoids and the larger stereospondylomorphs are frequently preserved with outlines of soft tissue around the skeleton.

[117] The holotype specimen of Arenaerpeton supinatus from the Triassic of New South Wales, Australia, displays extensive soft tissue, hinting at the girth of the animal in life.

Owen thought that the name Mastodonsaurus "ought not to be retained, because it recalls unavoidably the idea of the mammalian genus Mastodon, or else a mammilloid form of the tooth... and because the second element of the word, saurus, indicates a false affinity, the remains belonging, not to the Saurian, but to the Batrachian order of Reptiles.

Branchiosauria included only a few forms, such as Branchiosaurus from Europe and Amphibamus from North America, that had poorly developed bones, external gills, and no ribs.

[135] Other animals that would later be classified as temnospondyls were placed in a group called Ganocephala, which was characterized by plate-like skull bones, small limbs, fish-like scales and branchial arches.

[151][152][153][154][155][156] Other quantitative analyses have addressed morphometrics,[157][158][159][160] biomechanics,[161][162] Temnospondyls were also documented from an increasingly broad geographic and stratigraphic range in the 20th and 21st centuries, including the first occurrences from historically undersampled regions such as Antarctica,[163][164] Lesotho,[165] Japan,[166] Namibia,[167] New Zealand,[168] Niger,[169] and Türkiye.

[180] As temnospondyls continued to flourish and diversify in the Late Permian (260.4–251.0 Mya), a major group called Stereospondyli became more dependent on life in the water.

During the Early Triassic (251.0–245.0 Mya) one group of successful long-snouted fish-eaters, the trematosauroids, even adapted to a life in the sea, the only known batrachomorphs to do so with the exception of the modern crab-eating frog.

Large assemblages of Late Triassic metoposaurids with hundreds of individuals preserved together have been found in the southwestern United States, Morocco, India, and western Europe.

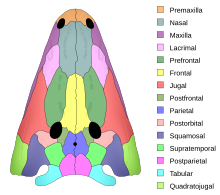

[197] Additional features were given by Godfrey et al. (1987), including the contact between the postparietal and exoccipital at the back of the skull, small projections (uncinate processes) on the ribs, and a pelvic girdle with each side having a single iliac blade.

The following cladogram is modified from Ruta et al. (2007):[150] Edops Cochleosauridae Dendrerpetontidae Trimerorhachis Neldasaurus Dvinosaurus Eobrachyopidae Brachyops Tupilakosauridae Capetus Saharastega Iberospondylus Palatinerpeton Parioxyidae Eryopidae Zatracheidae Trematopidae Dissorophidae Amphibamidae Stegops Eimerisaurus Branchiosauridae 7-14 Lysipterygium Actinodontidae Intasuchidae Melosauridae Archegosauridae Plagiosauridae Peltobatrachidae Lapillopsidae Rhinesuchidae Lydekkerinidae Indobrachyopidae Rhytidosteidae Brachyopidae Chigutisauridae Mastodonsauroidea Benthosuchus Thoosuchidae Almasauridae Metoposauridae Trematosauridae 1 Temnospondyli, 2 Edopoidea, 3 Dvinosauria, 4 Euskelia, 5 Eryopoidea, 6 Dissorophoidea, 7 Limnarchia, 8 Archegosauroidea, 9 Stereospondyli, 10 Rhytidostea, 11 Brachyopoidea, 12 Capitosauria, 13 Trematosauria, 14 Metoposauroidea The most basal group of temnospondyls is the superfamily Edopoidea.

Below is the cladogram from Schoch's analysis:[2] Edopoidea "Dendrerpetontidae" Dvinosauria Zatracheidae Dissorophoidea Eryopidae Sclerocephalus Glanochthon Archegosaurus Australerpeton Rhinesuchidae Lydekkerina Edingerella Benthosuchus Wetlugasaurus Watsonisuchus Capitosauroidea Brachyopoidea + Plagiosauridae Lyrocephaliscus Peltostega Trematosauridae Metoposauridae Modern amphibians (frogs, salamanders and caecilians) are classified in Lissamphibia.

Unlike Gerobatrachus, Doleserpeton was known since 1969, and the presence of pedicellate teeth in its jaws has led some paleontologists to conclude soon after its naming that it was a relative of modern amphibians.

Below is a cladogram modified from Sigurdsen and Bolt (2010) showing the relationships of Gerobatrachus, Doleserpeton and Lissamphibia:[61] Balanerpeton Dendrerpeton Sclerocephalus Eryops Ecolsonia Trematopidae Micromelerpeton Dissorophinae Cacopinae Eoscopus Platyrhinops Gerobatrachus Apateon Plemmyradytes Tersomius Micropholis Pasawioops Georgenthalia Amphibamus Doleserpeton Lissamphibia Chinlestegophis, a putative Triassic stereospondyl considered to be related to metoposauroids such as Rileymillerus, has been noted to share many features with caecilians, a living group of legless burrowing amphibians.

Plagiosuchus has very small teeth and a large area for muscle attachment behind the skull, suggesting that it could suction feed by rapidly opening its mouth.

Several types of dissorophoids, such as branchiosaurids, do not fully metamorphose, but retain features of juveniles such as external gills and small body size in what is known as neoteny.

An entire growth series is exhibited in the wide range of sizes among specimens, but the lack of terrestrially adapted adult forms suggests that these temnospondyls were neotenic.

To maintain a terrestrial lifestyle, a temnospondyl's limb bones would have to thicken with positive allometry, meaning that they would grow at a greater rate than the rest of the body.