Terence

Other traditional information about the life of Terence derives from the Vita Terenti, a biography preserved in Aelius Donatus' commentary, and attributed by him to Suetonius.

[2][3][4] However, it is not likely that Terence's contemporaries would have considered a dramatist important enough to write down his biography for posterity, and the narrative given by Suetonius' sources is often construed as conjecture based on the play texts and didascaliae.

[9] Admission was free to the entire population, seemingly on a first-come-first-served basis, except for the reservation of seats for members of the Senate after 194 BC; descriptions of 2nd Century theatre audiences refer to the presence of women, children, slaves, and the urban poor.

[10][11] In Greek New Comedy, from which the Roman comic tradition derived, actors wore masks which were conventionally associated with stock character types.

[12][13] However, most more recent authorities consider it highly likely that Roman actors of Terence's time did wear masks when performing this kind of play,[14][15][16] and "hard to believe"[17] or even "inconceivable"[18] that they did not.

Terence, shabbily dressed, went to the older poet's house when he was dining, and when Caecilius had heard only a few lines, he invited the young man to join him for the meal.

[40] R. C. Flickinger argues that the reported state of Terence's clothing shows that he had not yet become acquainted with his rich and influential patrons at the time of this meeting, and it was precisely Caecilius' death shortly thereafter, and the consequent loss of his support, which caused a two-year delay in production.

[41] All six of Terence's plays pleased the people; the Eunuchus earned 8,000 nummi, the highest price that had ever been paid for a comedy at Rome, and was acted twice in the same day.

[19] However, Dwora Gilula argues that the term nummus, inscribed on the title page in 161 BC, would refer to a denarius, a coin containing a much larger quantity of silver, so that the price paid for the Eunuchus was really 32,000 sesterces.

[4] It is possible that the fateful voyage to Greece was a speculative explanation of why he wrote so few plays inferred from Terence's complaint in Eunuchus 41–3 about the limited materials at his disposal.

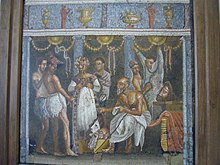

They have the plays in the order An., Eu., Hau., Ad., Hec., Ph.. Manuscript C is the famous Codex Vaticanus Latinus 3868, which has illustrations which seem to be copied from originals dating in style to the mid-third century.

Brothers, manuscript A, although it contains some errors, generally has a better text than Σ, which has a number of changes designed perhaps to make Terence easier to read in schools.

At a relatively early date, Terence's play texts began to circulate as literary works for a reading public, as opposed to scripts for the use of actors.

[77] Cicero (born 106 BC) recalls that when he was a boy, his education in rhetoric included an assignment to recount Simo's narrative from the first scene of the Andria in his own words.

[81] Terence was one of the few canonical classical authors to maintain a continuous presence in medieval literacy, and the large number of surviving manuscripts bears witness to his great popularity.

[82] Adolphus Ward said that Terence led "a charmed life in the darkest ages of learning,"[83] a remark approved by E. K. Chambers,[84] but Paul Theiner takes issue with this, suggesting that it is more appropriate to attribute "a charmed life" to authors who survived the Middle Ages by chance in a few manuscripts found in isolated libraries, whereas the broad and constant popularity of Terence "rendered elfin administrations quite unnecessary.

[86] Scores of Terentian maxims enjoyed such currency in late antiquity that they often lost nominal association with their author, with those who quoted Terence qualifying his words as a common proverb.

[87] Through the Middle Ages, Terence was frequently quoted as an authority on human nature and the mores of men, without regard for which character spoke the line or the original dramatic context, as long as the quotation was sententious in itself when separated from the rest of the play.

In a preface explaining her purpose in writing, Hrotsvit takes up Augustine's critique of the moral influence of the comedies, saying that many Christians attracted by Terence's style find themselves corrupted by his subject matter, and she has undertaken to write works in the same genre so that the literary form once used "to describe the shameless acts of licentious women" might be repurposed to glorify the chastity of holy virgins.

[96][97] Hrotsvit's indebtedness to Terence lies rather in situations and subject matter, transposed to invert the Terentian plot and its values; the place of the Terentian hero who successfully pursues a woman is taken by the girl who triumphs by resisting all advances (or a prostitute who abandons her former life), and a happy ending lies not in the consummation of the young couple's marriage, but in a figurative marriage to Christ.

Beatus Rhenanus writes that Erasmus, gifted in his youth with a tenacious memory, held Terence's comedies as closely as his fingers and toes.

[105] In the De ratione studii (1511), a central text for European curricula, Erasmus wrote, "among Latin authors, who is more useful for learning to speak than Terence?

[114] Chaerea's exultation upon coming out of Thais' house after the rape, declaring himself content to die in that blissful moment, also seems to be echoed in Othello II.1 and The Merry Wives of Windsor III.3.

[121] He recorded in his diary that "The Play is interesting, and many of the Sentiments are fine", and though he found the plot highly improbable, "the Critic can never find Perfection, and the person that is willing to be pleased with what he reads, is happier than he who is always looking for faults.

"[122] In 1816, John Quincy's son George Washington Adams performed in a school production of Andria in the role of the old man Crito, to the relief of the family, who had worried he might be given a less "respectable" part.

[124] Grandfather John, after rereading all six of Terence's comedies, also expressed apprehension about whether they were fit to be taught or exhibited to impressionable youths,[125] who lacked sufficient life experience to recognise certain characters and their deeds as morally repugnant and react appropriately.

[126] Accordingly, Adams undertook a month-long project to go through the plays excerpting approximately 140 passages that he considered illustrative of human nature as it is the same in all ages and countries, adding translations and comments explaining the moral lessons his grandsons should draw from the texts.

"[130] In 1834, when Charles read the works of Terence, copying in his grandfather's comments and making other notes, he responded, "In returning to answer these questions, I must disagree with the sentiment.

Due to his cognomen Afer, Terence has long been identified with Africa and heralded as the first poet of the African diaspora by generations of writers, including Juan Latino, Alexandre Dumas, Langston Hughes and Maya Angelou.

But the gossip, not discouraged by Terence, lived and throve; it crops up in Cicero and Quintilian, and the ascription of the plays to Scipio had the honour to be accepted by Montaigne and rejected by Diderot.