Territorial claims in the Arctic

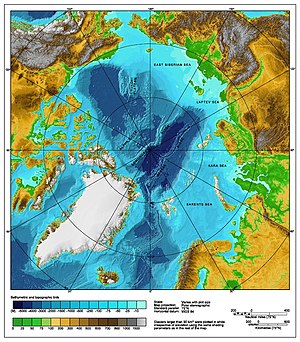

The sovereignty of the five surrounding Arctic countries is governed by three maritime zones as outlined in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea:[2] 1.

In the EEZ, the coastal state has the exclusive rights to explore and exploit natural resources found in the water column and on or under the seabed.

234 of the convention (also known as “the Canadian Clause”[4]) allows states to unilaterally apply special measures to protect the local environment and prevent vessel-source pollution[5] when the territory in their EEZ is covered with ice for most of the year.

[7] Norway, Russia, Canada, and Denmark launched projects to provide a basis for seabed claims on extended continental shelves beyond their exclusive economic zones.

[11] In the context of the Cold War, Canada sent Inuit families to the far north in the High Arctic relocation, partly to establish territoriality.

[15] Until 1999, the geographic North Pole (a non-dimensional dot) and the major part of the Arctic Ocean had been generally considered to comprise international space, including both the waters and the sea bottom.

"[22][23] In response, Sergey Lavrov, the Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs, stated "[w]hen pioneers reach a point hitherto unexplored by anybody, it is customary to leave flags there.

Such was the case on the Moon, by the way... [W]e from the outset said that this expedition was part of the big work being carried out under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, within the international authority where Russia's claim to submerged ridges which we believe to be an extension of our shelf is being considered.

"[24] On 25 September 2007, Prime Minister Stephen Harper said he was assured by Russian President Vladimir Putin that neither offence nor "violation of international understanding or any Canadian sovereignty" was intended.

[25][26] Harper promised to defend Canada's claimed sovereignty by building and operating up to eight Arctic patrol ships, a new army training centre in Resolute Bay, and the refurbishing of an existing deepwater port at a former mining site in Nanisivik.

[33][34] On 14 December 2014 Denmark claimed an area of 895,000 km2 (346,000 sq mi) extending from Greenland past the North Pole to the limits of the Russian Exclusive Economic Zone.

On November 27, 2006, Norway made an official submission into the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf in accordance with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (article 76, paragraph 8).

On December 20, 2001, Russia made an official submission into the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf in accordance with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (article 76, paragraph 8).

In the document it is proposed to establish the outer limits of the continental shelf of Russia beyond the 200-nautical-mile (370 km) Exclusive Economic Zone, but within the Russian Arctic sector.

[42] On August 2, 2007, a Russian expedition called Arktika 2007, composed of six explorers led by Artur Chilingarov, employing MIR submersibles, for the first time in history descended to the seabed at the North Pole.

The expedition aimed to establish that the eastern section of seabed passing close to the Pole, known as the Lomonosov and Mendeleyev Ridges, is in fact an extension of Russia's landmass.

Vladimir Putin made a speech on a nuclear icebreaker on 3 May 2007, urging greater efforts to secure Russia's "strategic, economic, scientific and defense interests" in the Arctic.

[46]Viktor Posyolov, an official with Russia's Agency for Management of Mineral Resources: With a high degree of likelihood, Russia will be able to increase its continental shelf by 1.2 million square kilometers [460,000 square miles] with potential hydrocarbon reserves of not less than 9,000 to 10,000 billion tonnes of conventional fuel beyond the 200-mile (320 km) [322 kilometer] economic zone in the Arctic Ocean[47]On August 4, 2015, Russia submitted additional data in support of its bid, containing new arguments based on "ample scientific data collected in years of Arctic research", for territories in the Arctic to the United Nations.

After the expedition "Arktika 2007" Russian researchers collected new data reinforcing Russia's claim to part of the sea bottom beyond its uncontested 200-mile Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) within its Arctic sector, the North Pole area included.

[52] In August 2007, an American Coast Guard icebreaker, the USCGC Healy, headed to the Arctic Ocean to map the sea floor off Alaska.

Larry Mayer, director of the Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping at the University of New Hampshire, stated the trip had been planned for months, having nothing to do with the Russians planting their flag.

[53] However, much research commentary since 2008 has thrown cold water on narratives that the Arctic will experience a rush for resources that could lead to conflict between states.

The potential value of the North Pole and the surrounding area resides not so much in shipping itself but in the possibility that lucrative petroleum and natural gas reserves exist below the seafloor.

[55][56] Further exploration for petroleum reserves elsewhere in the Arctic may now become more feasible, and the passage may become a regular channel of international shipping and commerce if Canada is not able to enforce its claim to it.

In 1973, Canada and Denmark negotiated the geographic coordinates of the continental shelf, and settled on a delimitation treaty that was ratified by the United Nations on December 17, 1973, and has been in force since March 13, 1974.

In July 2005, former Canadian defence minister Bill Graham made an unannounced stop on Hans Island during a trip to the Arctic; this launched yet another diplomatic quarrel between the governments, and a truce was called that September.

[63] There is an ongoing dispute involving a wedge-shaped slice on the International Boundary in the Beaufort Sea, between the Canadian territory of Yukon and the American state of Alaska.

[64] On August 20, 2009 United States Secretary of Commerce Gary Locke announced a moratorium on fishing the Beaufort Sea north of Alaska, including the disputed waters.

[66][67] Randy Boswell, of Canada.com wrote that the disputed area covered a 21,436 square kilometres (8,276 sq mi) section of the Beaufort Sea (smaller than Israel, larger than El Salvador).

[73] Consequently, the Northwest Passage remains a significant geopolitical issue, as its potential opening could shorten the cargo sea route between Europe and the Far East by at least 4,000 nautical miles.