Text comics

However, within the illustrations themselves no text is used: no speech balloons, no onomatopoeias, no written indications to explain where the action takes place or how much time has passed.

In the late 17th century and early 19th century picture narratives were popular in Western Europe, such as Les Grandes Misères de la guerre (1633) by Jacques Callot, History of the Hellish Popish Plot (1682) by Francis Barlow, the cartoons of William Hogarth, Thomas Rowlandson and George Cruikshank.

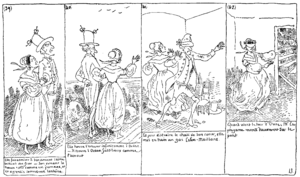

The earliest examples of text comics are the Swiss comics series Histoire de Mr. Vieux Bois (1827) by Rodolphe Töpffer, the French comics Les Travaux d'Hercule (1847), Trois artistes incompris et mécontents (1851), Les Dés-agréments d'un voyage d'agrément (1851) and L'Histoire de la Sainte Russie (1854) by Gustave Doré, the German Max und Moritz (1866) by Wilhelm Busch and the British Ally Sloper (1867) by Charles Henry Ross and Émilie de Tessier.

In the United States of America the speech balloon made its entry in comics with 1895's The Yellow Kid by Richard F. Outcault.

[1] As speech balloons asked for less text to read and had the advantage of linking the dialogues directly to the characters who were speaking or thinking, they allowed readers to connect better with the stories.

It even happened with the European Tintin in the Land of the Soviets (1929) by Hergé, which was republished in the French magazine Coeurs Vaillants, but with captions.

Translations of popular American comics such as Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck, Popeye throughout the 1930s and especially after the liberation of Europe in 1945 further encouraged the speech balloon format.