Thai language

These languages are written with slightly different scripts, but are linguistically similar and effectively form a dialect continuum.

[11][12] Ethnic minorities today are predominantly bilingual, speaking Thai alongside their native language or dialect.

[13] The Thai writing system has an eight-century history and many of these changes, especially in consonants and tones, are evidenced in the modern orthography.

According to a Chinese source, during the Ming dynasty, Yingya Shenglan (1405–1433), Ma Huan reported on the language of the Xiānluó (暹羅) or Ayutthaya Kingdom,[e] saying that it somewhat resembled the local patois as pronounced in Guangdong[14]: 107 Ayutthaya, the old capital of Thailand from 1351 - 1767 A.D., was from the beginning a bilingual society, speaking Thai and Khmer.

Bilingualism must have been strengthened and maintained for some time by the great number of Khmer-speaking captives the Thais took from Angkor Thom after their victories in 1369, 1388 and 1431.

An investigation of the Ayutthaya Rajasap reveals that three languages, Thai, Khmer and Khmero-Indic were at work closely both in formulaic expressions and in normal discourse.

The maximal four-way occurred in labials (/p pʰ b ʔb/) and denti-alveolars (/t tʰ d ʔd/); the three-way distinction among velars (/k kʰ ɡ/) and palatals (/tɕ tɕʰ dʑ/), with the glottalized member of each set apparently missing.

The major change between old and modern Thai was due to voicing distinction losses and the concomitant tone split.

The above consonant mergers and tone splits account for the complex relationship between spelling and sound in modern Thai.

[g] หม ม หน น, ณ หญ ญ หง ง ป ผ พ, ภ บ ฏ, ต ฐ, ถ ท, ธ ฎ, ด จ ฉ ช ก ข ค, ฆ อ ฝ ฟ ศ, ษ, ส ซ ฃ ฅ ห หร ร หว ว หล ล หย ย อย Early Old Thai also apparently had velar fricatives /x ɣ/ as distinct phonemes.

It is unclear whether Sanskrit and Pali words beginning with /ɲ/ were borrowed directly with a /j/, or whether a /ɲ/ was re-introduced, followed by a second change /ɲ/ > /j/.

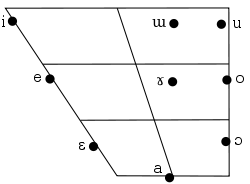

Pittayaporn (2009[full citation needed]), for example, reconstructs a similar system for Proto-Southwestern-Tai, but believes that there was also a mid back unrounded vowel /ə/ (which he describes as /ɤ/), occurring only before final velar /k ŋ/.

Standard Thai distinguishes three voice-onset times among plosive and affricate consonants: Where English makes a distinction between voiced /b/ and unvoiced aspirated /pʰ/, Thai distinguishes a third sound – the unvoiced, unaspirated /p/ that occurs in English only as an allophone of /pʰ/, for example after an /s/ as in the sound of the p in "spin".

Of the consonant letters, excluding the disused ฃ and ฅ, six (ฉ ผ ฝ ห อ ฮ) cannot be used as a final and the other 36 are grouped as following.

Thai has specific phonotactical patterns that describe its syllable structure, including tautosyllabic consonant clusters, and vowel sequences.

In core Thai words (i.e. excluding loanwords), only clusters of two consonants occur, of which there are 11 combinations: The number of clusters increases in loanwords such as /tʰr/ (ทร) in อินทรา (/ʔīn.tʰrāː/, from Sanskrit indrā) or /fr/ (ฟร) in ฟรี (/frīː/, from English free); however, these usually only occur in initial position, with either /r/, /l/, or /w/ as the second consonant sound and not more than two sounds at a time.

The language being analytic and case-less, the relationship between subject, direct and indirect object is conveyed through word order and auxiliary verbs.

'In order to convey tense, aspect and mood (TAM), the Thai verbal system employs auxiliaries and verb serialization.

'ฉันchan/tɕʰǎnจะchatɕàʔกินkinkīnที่thithîːนั่นnannânพรุ่งนี้phrungnipʰrûŋ.níː/ฉัน จะ กิน ที่ นั่น พรุ่งนี้chan cha kin thi nan phrungni/tɕʰǎn tɕàʔ kīn thîː nân pʰrûŋ.níː/'I'll eat there tomorrow.

[26] The imperfective aspect marker กำลัง (kamlang, /kām lāŋ/, currently) is used before the verb to denote an ongoing action (similar to the -ing suffix in English).

เขาkhao/kʰǎw3SGได้daidâːjPSTกินkinkīn/eatเขา ได้ กินkhao dai kin/kʰǎw dâːj kīn/3SG PST eatHe ate.เขาkhao/kʰǎw3SGกินkinkīneatแล้วlaeolɛ́ːw/PRFเขา กิน แล้วkhao kin laeo/kʰǎw kīn lɛ́ːw/3SG eat PRFHe has eaten.เขาkhao/kʰǎw3SGได้daidâːjPSTกินkinkīneatแล้วlaeolɛ́ːw/PRFเขา ได้ กิน แล้วkhao dai kin laeo/kʰǎw dâːj kīn lɛ́ːw/3SG PST eat PRFHe's already eaten.Future can be indicated by จะ (cha, /tɕàʔ/; 'will') before the verb or by a time expression indicating the future.

เขาkhao/kʰǎwheไปpaipājgoกินkinkīneatข้าวkhaokʰâːw/riceเขา ไป กิน ข้าวkhao pai kin khao/kʰǎw pāj kīn kʰâːw/he go eat rice'He went out to eat'ฉันchan/tɕʰǎnIฟังfangfāŋlistenไม่maimâjnotเข้าใจkhao chaikʰâw tɕāj/understandฉัน ฟัง ไม่ เข้าใจchan fang mai {khao chai}/tɕʰǎn fāŋ mâj kʰâw tɕāj/I listen not understand'I don't understand what was said'เข้าkhao/kʰâwenterมาmamāː/comeเข้า มาkhao ma/kʰâw māː/enter come'Come in'ออกok/ʔɔ̀ːkexitไป!paipāj/goออก ไป!ok pai/ʔɔ̀ːk pāj/exit go'Leave!'

Possession in Thai is indicated by adding the word ของ (khong) in front of the noun or pronoun, but it may often be omitted.

For example: The particles are often untranslatable words added to the end of a sentence to indicate respect, a request, encouragement or other moods (similar to the use of intonation in English), as well as varying the level of formality.

[36][citation needed] Rhetorical, religious, and royal Thai are taught in schools as part of the national curriculum.

Thus, the word 'eat' can be กิน (kin; common), แดก (daek; vulgar), ยัด (yat; vulgar), บริโภค (boriphok; formal), รับประทาน (rapprathan; formal), ฉัน (chan; religious), or เสวย (sawoei; royal), as illustrated below: Thailand also uses the distinctive Thai six-hour clock in addition to the 24-hour clock.

Chinese-language influence was strong until the 13th century when the use of Chinese characters was abandoned, and replaced by Sanskrit and Pali scripts.

As a result, it is impossible for Thais, past and present, to engage in a conversation without incorporating Khmer loanwords in any given topic.

Since the beginning of the 20th century, however, the English language has had the greatest influence, especially for scientific, technical, international, and other modern terms.

Their influence in trade, especially weaponry, allowed them to establish a community just outside the capital and practise their faith, as well as exposing and converting the locals to Christianity.