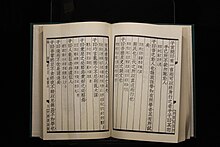

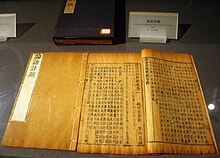

Analects

During the late Song dynasty (960–1279 AD) the importance of the Analects as a Chinese philosophy work was raised above that of the older Five Classics, and it was recognized as one of the "Four Books".

The Analects has been one of the most widely read and studied books in China for more than two millennia; its ideas continue to have a substantial influence on East Asian thought and values.

Confucius believed that the welfare of a country depended on the moral cultivation of its people, beginning from the nation's leadership.

Confucius' primary goal in educating his students was to produce ethically well-cultivated men who would carry themselves with gravity, speak correctly, and demonstrate consummate integrity in all things.

The Qing dynasty philologist Cui Shu argued on linguistic ground that the last five books were produced much later than the rest of the work.

[9] In 2015, the Anhui University acquired a corpus of excavated Warring States period bamboo strips, and they contained fragments of the Analects corresponding to the received text.

[13] The old text version got its name because it was written in characters not used since the earlier Warring States period (before 221 BC), when it was assumed to have been hidden.

[19] The Anhui University in 2015 acquired a corpus of excavated Warring States period bamboo slips that contained fragments of the Analects that corresponded to the received text.

The Analects was considered secondary as it was thought to be merely a collection of Confucius's oral "commentary" (zhuan) on the Five Classics.

In his work, He Yan collected, selected, summarized, and rationalized what he believed to be the most insightful of all preceding commentaries on the Analects which had been produced by earlier Han and Wei dynasty (220–265 AD) scholars.

[26] He Yan's personal interpretation of the Lunyu was guided by his belief that Daoism and Confucianism complemented each other, so that by studying both in a correct manner a scholar could arrive at a single, unified truth.

The Explanations that was written in 248 AD, was quickly recognized as authoritative, and remained the standard guide to interpreting the Analects for nearly 1,000 years, until the early Yuan dynasty (1271–1368).

The principal biography available to historians is included in Sima Qian's Records of the Grand Historian, but because the history contains a significant amount of material unverifiable in other sources and possibly legendary, the biographical material on Confucius found in the Analects makes the Analects arguably the most reliable source of biographical information about Confucius.

Confucius instead used the term ren to describe an extremely general and all-encompassing state of virtue, one which no living person had attained completely.

According to Confucius, a person with a well-cultivated sense of ren would speak carefully and modestly (§12.3); be resolute and firm (§12.20), courageous (§14.4), free from worry, unhappiness, and insecurity (§9.28; §6.21); moderate their desires and return to propriety (§12.1); be respectful, tolerant, diligent, trustworthy and kind (§17.6); and love others (§12.22).

[32] To Confucius, the cultivation of ren involved depreciating oneself through modesty while avoiding artful speech and ingratiating manners that would create a false impression of one's own character (§1.3).

[30] Confucius taught that the ability of people to imagine and project themselves into the places of others was a crucial quality for the pursuit of moral self-cultivation (§4.15; see also §5.12; §6.30; §15.24).

[33] Confucius regarded the exercise of devotion to one's parents and older siblings as the simplest, most basic way to cultivate ren.

He believed that subjecting oneself to li did not mean suppressing one's desires but learning to reconcile them with the needs of one's family and broader community.

[30] By leading individuals to express their desires within the context of social responsibility, Confucius and his followers taught that the public cultivation of li was the basis of a well-ordered society (§2.3).

[30] Confucius taught his students that an important aspect of li was observing the practical social differences that exist between people in daily life.

He argued that the demands of ren and li meant that rulers could oppress their subjects only at their own peril: "You may rob the Three Armies of their commander, but you cannot deprive the humblest peasant of his opinion" (§9.26).

[34] Confucius believed that the social chaos of his time was largely due to China's ruling elite aspiring to, and claiming, titles of which they were unworthy.

[34] Confucius judged a good ruler by his possession of de ('virtue'): a sort of moral force that allows those in power to rule and gain the loyalty of others without the need for physical coercion (§2.1).

Examples of rituals identified by Confucius as important to cultivate a ruler's de include: sacrificial rites held at ancestral temples to express thankfulness and humility; ceremonies of enfeoffment, toasting, and gift exchanges that bound nobility in complex hierarchical relationships of obligation and indebtedness; and, acts of formal politeness and decorum (i.e. bowing and yielding) that identify the performers as morally well-cultivated.

(§3.8)[36] His primary goal in educating his students was to produce ethically well-cultivated men who would carry themselves with gravity, speak correctly, and demonstrate consummate integrity in all things (§12.11; see also §13.3).

Simon Leys, who recently translated the Analects into English and French, said that the book may have been the first in human history to describe the life of an individual, historic personage.

[41] Within these incipits, a large number of passages in the Analects begin with the formulaic ziyue, "The Master said," but without punctuation marks in classical Chinese, this does not confirm whether what follows ziyue is direct quotation of actual sayings of Confucius, or simply to be understood as "the Master said that.." and the paraphrase of Confucius by the compilers of the Analects.

[45] The Analects and its commentaries are applied in a multitude of cultural expressions throughout East and South-East Asia, in countries like China, Japan, Korea (both North and South), Thailand and Vietnam.

[53][54] The text is still influential in the practice and teaching of such martial arts in contemporary time, including in relation to their social and political dynamics.