Blond Angel case

Depending on the angle chosen, those that aim to shed light on the context highlight the vulnerability of Romani minorities to child trafficking, the particular severity of the discrimination they suffer in Greece, the "official invisibility" that surrounds them throughout Europe, or a political climate marked by a continent-wide tightening of national policies against them.

On October 16, 2013,[1] in a Romani camp near Farsala, in central Greece,[2] police officers conducting a routine[1] search for drugs and weapons[2] were struck by the appearance of a four-to six-year-old girl: her blond hair, very pale skin and green eyes set her apart from both the four matte-skinned children she was playing[1] with and the dark-skinned brunette[3] couple staying nearby.

[6] These include the case of Lisa Irwin, reported missing in 2011 at the age of 11 months[1] from Kansas, and that of Greek parents, one of them of Scandinavian origin, who lost a daughter at birth in 2009, whose body was never returned to them, and who after obtaining an exhumation found her coffin empty.

From October 22 onwards, dozens of articles in the daily papers denounced prejudice against the Romani and the family dramas it entailed, as well as the excesses of official services accused of engaging in racial profiling.

At the same time, the Kos police received video footage of a religious ceremony filmed near Limassol, in southern Cyprus: in the midst of a group of Roma, a young man with light brown hair and blue eyes appeared, resembling the composite of the missing child.

[27] Dezideriu Gergely, head of the Budapest-based European Roma Rights Centre (ERRC), pointed out that not all Romani are dark-skinned, and that some are light-skinned and green-eyed,[8] and deplored the effect of the propagation of hostile prejudice in the Irish case.

[28] Regarding the two Irish "blond angels", in a report published in July 2014, Children's Ombudsman Emily Logan concluded that racial profiling had indeed taken place, that the suspicions of abduction had no basis other than preconceived ideas endorsed under the influence of the media hysteria surrounding the Greek case, and that no immediate urgency justified the actions taken.

[31] On the BBC News website, Paul Kirby took up the general data on child trafficking activities around Romani communities: UNICEF estimated that at least 3,000 children in Greece were in the hands of networks originating from Bulgaria, Romania and other Balkan countries; most cases were probably not the result of abductions, but rather purchases and sales concluded for a few thousand euros.

Similarly, the European Roma Rights Centre (ERRC), while refusing to link the fact to cultural or community factors, acknowledged that the Romani are a vulnerable group, due to their extreme poverty and low levels of income and education.

[6] In September 2014, while Maria Roussev's parents were still suspected of having sold their daughter, Clémentine Fitaire, on the Aufeminin website, made the connection with a new case of child trafficking that the Greek police had just announced had been dismantled: six individuals, including a pediatrician and a notary, were bringing pregnant women in precarious situations from Bulgaria to Greece, to give birth; the babies were then resold to couples applying for adoption, for around 10,000 euros.

[34] In October 2014, a year after the affair broke, Nikolia Apostolou, an Athenian writer and filmmaker writing on the Open Society Foundations website, noted no significant improvement, but rather a strengthening of prejudice.

There were signs of progress here and there: in Examilia, near Corinth, for example, after years of effort, the young players of the Romani soccer team noticed a change in the attitude of the inhabitants of the neighboring town, who now come to watch their matches.

Added to this are the legal and procedural difficulties which, according to the association leader, often and deliberately prevent people from obtaining identity documents: in his view, they show that the invisibility of the Romani is politically and economically convenient for governments which would otherwise have to guarantee their access to education, health, justice, representation in the civil service, participation in elections, etc.

In September 2013, referring to the dismantling of camps, the French Interior Minister, the Socialist Manuel Valls, declared, "These populations have lifestyles that are extremely different from ours, and which are obviously in confrontation, we have to take that into account, it does mean that the Romani are destined to return to Romania or Bulgaria."

The following month, on the subject of opening the borders to Bulgarian and Romanian workers, David Cameron, the British Conservative Prime minister, warned: "if people are not here to work — if they are begging or sleeping rough — they will be removed".

[40] In terms of child protection, Jana Hainsworth, from the Eurochild network of associations, has found the case to be an illustration of an all-too-common trend: the demonization of "bad" parents, to the detriment of a more attentive approach to the complexity of families' situations.

[12] For both her and Huus Dijksterhuis, of the European Romani advocacy network ERGO, separating a child from his or her family is a solution that should only be considered as a last resort, and should not detract from efforts to help marginalized communities, based on a systemic analysis of the causes of their exclusion.

According to residents' testimonies, her situation was neither the result of kidnapping nor human trafficking, but rather of a form of informal adoption; moreover, her biological father continued to visit her, most recently five days before the investigators intervened, while her mother was in Sofádes, a village a few dozen kilometers away.

On October 19, speaking to the press, the regional police spokesman mentioned several possibilities: abduction from a hospital, as the result of an isolated act or as part of a trafficking operation, abandonment by a single mother.

[10] And when, as in the Irish press reversal, the dialectic of the cliché and its deconstruction have shown their limits as a factor of dramatization, the defense of the threatened family unit remains a recourse, even if for the benefit of Romanis admitted on this occasion to the status of citizens and parents.

[10] On the website of the European participative magazine Cafébabel, Giannis Mavris assessed the coverage of the case by the Greek media, which he pointed out were particularly distrusted in this country, not least for having played no warning role before the economic crisis.

[43] On the website of the Institute of Race Relations, Ryan Erfani-Ghettani reminisced about how the Greek television stations (Alpha and Skai) in Farsala exploited family videos and expressions of affection from the neighborhood: to show that the little girl was raised by the whole community with the aim of making money, first through begging, then through the sex trade.

[43] As for the international media, according to Natasha Dukach's analysis on the Fair Observer website, they did not sufficiently verify the information produced by the Greek press and repeated a biased presentation of the case, contributing to the promotion of stereotypes.

These included their silence on the fact that little Maria's ethnic origin had been stated from the outset of the investigation by the couple who raised her; or the propagation of false information, such as the assertion that the child's biological mother had taken the initiative to claim maternity, when she was only identified following a search and after DNA tests had ruled out all putative parents.

[45] Krystal Thomas, author of an academic work on the situation of the Romani in the European Union, highlighted how Maria's "mystery", by occupying the headlines, put these populations under the gaze of the rest of the international community:[46] her instant disappearance, without any analysis of the negative stereotypes that had been disseminated, ultimately led to increased discontent.

[47] Estrella Israël-Garzón and Ricardo Ángel Pomares-Pastor, respectively professor[48] and researcher[49] in communication sciences, for their part studied how the affair was covered by the television news of several European public channels (BBC, France 2, Rai 1 and La 1), from October 19 to 22, 2013.

[51] Ultimately, for the two academics, the coverage of the case, which deviated from the applicable quality standards, showed how "necessary is a more rigorous and plural treatment of information, where intercultural and ethical criteria would help to overcome the barrier of excluding difference".

[5] On this basis, the analyst compared the British, French and Irish press, illustrating how the use of Romani portrayals varied according to national contexts: With regard to the Irish case, Ryan Erfani-Ghettani pointed out that, prior to this inflexion, the press, influenced by the Greek case, had indeed succeeded in creating a self-sustaining hysteria, with rumor-driven actions by the authorities becoming evidence of the reality of the abductions; and that Emily Logan's report had also reminded the media of their obligations, notably in terms of privacy protection (the released little girl had not been able to return to her home besieged by journalists).

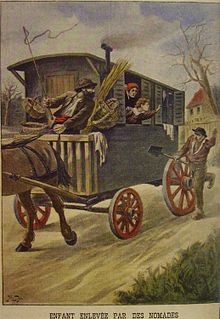

[59] As Isabelle Ligner has explained, it was widespread in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when it was also propagated by the press in a context of repression of "nomadic" populations, considered an integral part of the "dangerous classes".

[8] For political scientist Huub van Baar, the case illustrates, along with many others, the damage that unfounded allegations can cause, especially when the police, media and politicians failed to denounce the abuse of stereotyped images, if they didn't indulge in it themselves.