Committee on Alleged German Outrages

[1] The report is seen as a major propaganda form that Britain used in order to influence international public opinion regarding the behaviour of Germany, which had invaded Belgium the year before.

The report was translated by the end of 1915 into every major European language and had a profound impact on public opinion in Allied and neutral countries, particularly in the United States.

Prime Minister H. H. Asquith responded on 15 September by authorizing the Home Secretary and the Attorney General to investigate allegations of violations of the laws of war by the German Army.

In the end, some 1,200 witnesses were interviewed by teams of barristers appointed by George A. Aitken, Assistant Home Secretary, who directed the investigation, and by clerks in the Attorney General's Office.

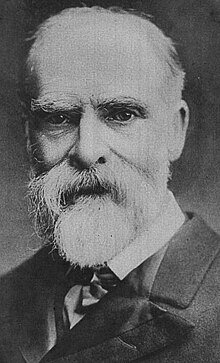

On 4 December James Bryce was asked to chair the "German Outrages Inquiry Committee", which would review the material that had been collected and issue a report.

The mission of this committee was to review the "charges that German soldiers, either directed or condoned by their officers, had been guilty of widespread atrocities in Belgium.

Still more important for the government, Bryce was a respected figure in both Britain and the United States, where he had been the British ambassador from 1907 to 1913, and was a friend of President Wilson.

In public statements and private correspondence, Bryce claimed that he hoped to exonerate the German Army from accusations of barbarism.

[4] By selecting Bryce to be head of the committee, it was believed that the research and findings completed would be reviewed with extreme care and that it would hold the guilty responsible for their actions.

By the beginning of March 1915, Harold Cox began to have reservations about some of the depositions and about the limited role the committee was playing in the investigation.

As a result, the committee states within the Bryce Report that "many depositions have thus been omitted on which, although they are probably true, we think it safer not to place reliance.

[6] By removing the extreme witness accounts from its report, the committee believed it had "eliminated utterly unreliable and unsupported statements.

The report was divided into two parts: Belgium was guaranteed by a Treaty in 1839, that no nation was to have the right to claim the passage for its army through a neutral state.

After having "narrated the offenses committed in Belgium, which it has been proper to consider as a whole, we now turn to another branch of the subject, the breaches of the usages of war which appear in the conduct of the German army general.

The Report came to four conclusions about the behavior of the German Army: The committee determined that "these excesses were committed – in some cases ordered, in others allowed – on a system and in pursuance of a set purpose.

That purpose was to strike terror into the civil population and dishearten the Belgian troops, so as to crush down resistance and extinguish the very spirit of self-defence.

A column titled "The Daily German Lie" linked support for the report's authenticity to a War Department request for a ban on printing unsubstantiated atrocity stories.

But, based on their own conclusions, most neutral countries, especially the United States, came to connect the German army with the term ‘atrocity’ during World War I.

Immediately after World War I, the original documents of the Belgian witness depositions could not be found in the British Home Office, where they were supposed to be kept for protection.

[2] The committee did not personally interview a single witness, openly and clearly stating in its preamble that it relied instead on depositions given without oaths and hearsay evidence which it considered to be independently corroborated.

As to the specific charges made by inter-war revisionists, there is no evidence that the report was rushed into print five days after the sinking of the Lusitania in order to capitalize on the outrage caused by that event.

The Belgian government requested that witnesses not be identified by name for fear of reprisals against relatives and friends in occupied Belgium.

It is in the region designated “The Aershot, Malines, Vilvorde, Louvain Quadrangle,” where the majority of the testimony comes from soldiers, that the most dubious depositions occur.

There is no evidence that committee members felt that the graver charges would not be believed in if the more sensationalist accusations were dismissed, as Wilson claims.

[21][22] However, historians focusing on the actions of the German army in Belgium have found Bryce's work to be "substantially accurate".

[23][24] Bennett writes that Bryce's Committee had an honest intent to find the truth, and its major allegations were supported by historical evidence.

However its methodological flaws, inclusion of some lurid anecdotes, and association with the Allied war effort made it vulnerable to attack by postwar revisionists and pro-German propagandists.