The Catcher Was a Spy

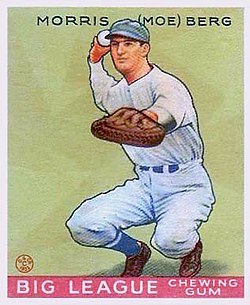

The Catcher Was a Spy: The Mysterious Life of Moe Berg is a 1994 biography written by Nicholas Dawidoff about a major league baseball player who also worked for the Office of Strategic Services, the forerunner of the Central Intelligence Agency.

[1] Moe Berg, the subject of the book, was an enigmatic person who hid much of his private life from those who knew him and who spent his later decades as a jobless drifter living off the good will of friends and relatives.

The couple, along with their three children lived in the Harlem section of New York City until 1906 when Bernard Berg bought a pharmacy in West Newark, New Jersey.

[4] Always an excellent student, Berg studied seven languages: Latin, Greek, French, Spanish, Italian, German, and Sanskrit and subsequently received a B.A.

Although he was not a good hitter and was a slow baserunner, his fielding, arm strength, and knowledge of the game led to his being appointed as team captain in his senior season.

During the early part of his career, Berg attended Columbia Law School, causing him to miss several weeks of spring training for the White Sox.

Although Berg was only a backup catcher, his proficiency in the Japanese language resulted in his joining Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, and Jimmie Foxx on the team.

The film footage proved to be valuable as the increasingly militarized Japan had restricted the movement of foreigners and made it extremely difficult for outsiders to gather intelligence.

[8] By the time Berg's career was coming to an end, he had gained a reputation as one of the game's smartest players, and was a favorite of newspaper reporters who enjoyed writing the storyline of the Princeton language scholar and New York lawyer who was also a big league catcher.

But the final years Berg spent as a player, and then a coach, for the Red Sox caused both teammates and reporters to raise questions about his actual role with the team.

[10] However, Berg soon began looking for ways to make a more pivotal contribution to the war effort and decided to apply for a position with the Office of Strategic Services (OSS).

His application was accepted[11] and subsequently, he spent the majority of his time in Europe, performing a variety of missions, many of them related to Germany's work on nuclear energy and atomic weapons.

Later, Berg befriended Heisenberg, and along with his other work both in Switzerland and later in Italy, helped convince U.S. military officials that Germany was not on the verge of developing an atomic bomb.

When people asked Berg what he did for a living, he would slowly draw his finger to his lips as if to silence both the question and answer, giving the impression that he was still involved in spying, which he was not.

While the foregoing analysis may sound presumptuous in summary, in Mr. Dawidoff's sensitive treatment it seems both tasteful and plausible [and] Moe Berg's life finally makes sense.

"[19]"Berg claimed that he had taken films in Japan during an off-season baseball barnstorming tour in 1934 that were useful to the U.S. military after Pearl Harbor, and that he had worked for the OSS in Europe during the war, assessing whether Germany might make good on its promise to use an atomic device as its last, and most devastating, super-weapon.

Dawidoff has accumulated a vast body of information in a remarkable job of research, especially considering that Berg, who died of a heart attack at age 70 in 1972, deliberately cloaked the details of his life in mystery.

Rather, he presents an almost legalistic mass of evidence to prove that Berg followed up a career (1923–39) as a pseudo intellectual, third-string catcher by becoming a mediocre WW II spy, and then spent the last 25 years of his life as an unemployed vagabond, living off his charm and his wit and his vast store of friends.