The Colossus of Rhodes (Dalí)

Pressured by financial concerns after his move to the United States in 1940, and influenced by his fascination with Hollywood, Dalí shifted focus away from his earlier exploration of the subconscious and perception, and towards historical and scientific themes.

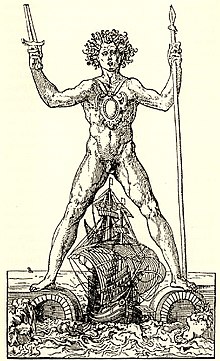

Maryon proposed that the historical Colossus was hollow, formed from hammered bronze plates, and located alongside the harbour rather than astride it.

[2] The statue stood until the 226 BC Rhodes earthquake, when, according to Pliny the Elder three centuries later in his Naturalis Historia, it buckled and fell.

[3] In his ninth-century AD Chronographia, Theophanes the Confessor wrote that its ruins remained until 652–53, when Muawiyah I conquered Rhodes and the Colossus was sold for scrap.

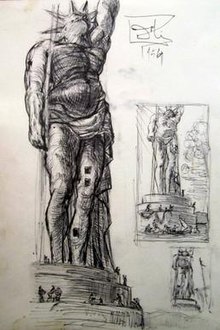

[14] Helios raises his right hand to shield his eyes from the sun over which he reigns, giving what the art historian Eric Shanes terms "a vaguely Surrealist touch" to Dalí's work.

[35] His move to the United States in 1940 caused financial pressures, but brought to the fore his flair for showmanship, helping to develop his relationship with Hollywood.

[36] As World War II ended, Dalí's work turned towards the historical and religious, fused with aspects from modern culture and commercial art.

[32][36] The Colossus of Rhodes exemplifies Dalí's preoccupations with cinema, history, and science, and his loosening grip on surrealism.

[37] Compared with Maryon's paper, writes the scholar Godefroid de Callataÿ, the painting "does not look extremely original".

[14] Dalí copied the likeness of the Colossus put forth by Maryon, clearly depicting hammered plates of bronze, and showing the same tripod structure of a figure supported by a piece of drapery.

[45] Coupled with rampant forgeries of an easily faked signature, this—termed by Shanes "one of the largest and most prolonged acts of financial fraud ever perpetrated in the history of art"—caused the lithographs to become virtually worthless.