The Egyptian

His tone expresses cynicism, bitterness and disappointment; he says humans are vile and will never change, and that he's writing down his story for therapeutic reasons alone and for something to do in the rugged and desolate desert landscape.

Ashamed and dishonored, Sinuhe arranges his adoptive parents to be embalmed and buries them in the Valley of the Kings (they had taken their lives before eviction), after which he decides to go to exile in the company of Kaptah to Levant, which was under Egyptian rule at the time.

Sinuhe and his companions feel unhappy about the militarism and tough rule of law that characterize the kingdom of the Hittites, and they decide to leave Anatolia and sail to Crete, Minea's homeland.

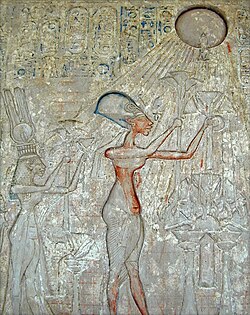

After a particularly violent public incident, Akhenaten, fed up with opposition, leaves Thebes with Sinuhe to middle Egypt where a new capital, Akhetaten, dedicated to Aten, is built.

Sinuhe later succeeds with Horemheb's and Ay's mission to assassinate the Hittite prince Shubattu, secretly invited by Baketamon to marry her, preventing him from reaching Egypt and seizing the throne.

Although Waltari employed some poetic license in combining the biographies of Sinuhe and Akhenaten, he was otherwise much concerned about the historical accuracy of his detailed description of ancient Egyptian life and carried out considerable research into the subject.

[8] Waltari didn't make notes, instead preferring to internalise all this vast knowledge; this allowed him to interweave his accumulated information smoothly into the story.

In it, Waltari explored the disastrous consequences of Akhenaten's well-intentioned implementation of unconditional idealism in a society,[8] and referenced the tensions at the borders of the Egyptian empire which resemble those on the Soviet-Finnish frontier.

[11] Waltari also witnessed Finland's sudden, perfidious change of policy towards the USSR from "enemy" to "friend" upon the signing of the armistice on 4 September 1944, another ideal shattered.

[12] The war provided the final impulse for exploring the subjects of Akhenaten and Egypt in a novel which, although depicting events that took place over 3,300 years ago, in fact reflects the contemporary feelings of disillusionment and war-weariness and pessimistically illustrates how little the essence of humanity has changed since then.

[8] So intense was his state of inspiration and immersion that, in a fictionalised account called A Nail Merchant at Nightfall he would write later, he claimed to have been visited by visions of Egyptians and to have simply transcribed the story as dictated by Sinuhe himself.

[8] Envall brings up the "familiarity" of the depiction of 14th-century BC Egypt as highly developed: the novel describes phenomena – inventions, knowings, institutions etc.

[26] As examples of these cultural parallels, Envall lists: the pseudo-intellectuals exalt themselves by flaunting their usage of foreign loanwords; the language of Babylon is the common language of the learned throughout various countries (like Greek in the Hellenistic period, Latin in the medieval period, French among diplomats and English in the 20th and 21st centuries); education takes place in faculties that provide degrees for qualification in posts (European universities began in the Middle Ages); people have addresses and send mail as papyrus and clay tablets; censorship is circumvented by cloaking subjects with historical stand-ins.

[27] Similar themes are expressed via repetition throughout the novel, such as: everything is futile, the tomorrow is unknowable, no one can know why something has always been so, all people are fundamentally the same everywhere, the world year is changing, and death is better than life.

[40] The relations between nations of the two time periods look as follows:[41] The similarities between the warlike Hittites and Nazi Germany include their Lebensraum project, fast sudden warfare or Blitzkrieg, use of propaganda to weaken the enemy, and worship of health and power while disdaining the sickly and weak.

Akhenaten's and Horemheb's battle for power mirrors the opposition of Neville Chamberlain and Winston Churchill; the former seeks peace by conceding lands to the invader but helps the enemy, whereas the latter knows that war is the only way to save the home country.

[38] The novel's reputation of historical flawlessness has been often repeated, by the egyptological congress of Cairo,[42][43] French egyptologist Pierre Chaumelle,[42][44] and U. Hofstetter of The Oakland Post.

[48][52] Waltari's unflattering characterisation of Akhenaten, Horemheb, Tiy and Ay as flawed persons proved to be closer to reality than their earlier glorification.

[52] Some have doubted the possibility of an ancient Egyptian person writing a text for oneself only, but in 1978 such a papyrus became public; its author, a victim of wrongdoing, tells his life story in it with no recipient.

[53] According to Jussi Aro, the real Hittites were seemingly less cruel and stern than other peoples of the Middle East and the day of the false king was misdated among other errors,[48] although Panu Rajala dismisses his claims as alternative readings of evidence rather than outright contradictions.

[51] Markku Envall argues that the accuracy or lack thereof is irrelevant to a fictional work's literary merit, citing the errors of Shakespeare.

Eino Sormunen of Savon Sanomat recommended discretion due to plenitudes of horrifying decadence at display, and Vaasan Jaakkoo of Ilkka warned about it as unsuitable for children.

Yrjö Tönkyrä of Kaiku wrote: "Not wanting to appear in any way as a moralist, I nonetheless cannot ignore the erotic gluttony that dominates the work, as if conceived by a sick imagination – the whole world revolves for the sole purpose that people can enjoy..."[quote 9][61][2] French egyptologist Pierre Chaumelle read The Egyptian in Finnish and, in a letter featured in a Helsingin Sanomat article in 13.

"[quote 10][2][44]Critics had been concerned that Waltari might have played fast and loose with historical events, but this article dispelled these doubts and begot a reputation of almost mythical accuracy around the novel.

If there are deeps of the personality that Mann plumbs further, Waltari makes an exciting, vivid, and minute re-creation of the society of Thebes and of Egypt and the related world in general, ranging from Pharaoh and his neighbor kings to the outcast corpse-washers in the House of the Dead.

"[4] Gladys Schmitt, writing for The New York Times, commented on the unresolved philosophical dilemma posed between Ekhnaton's generosity for bettering the world and Horemheb's pragmatic belligerence for stability, and praised the vibrancy and historical research evident in the characterisation of countries and social classes; however, she criticised social struggles surrounding Akhenaton as obscured, and found events oversensational and the characters composed of predictable types.

"[66] Soon after its release in the USA, it was selected book of the month in September 1949, and then entered the bestseller lists in October 1949, where it remained the unparalleled two years – 550 000 copies were sold in that time.

This stigma he had gained for perceived overproductivity, superficiality and looseness of style;[8] for his popular erotic flavouring in clearly told stories;[69] and not conforming to the "Great Tradition" of Finnish literature (patriotic, realistic depiction of the struggles of poor yet courageous Finns with nature and society) favoured by critics at the time.

[70] Despite its popularity and acclaim, the novel was denied the 1946 state literature award, largely due to the efforts of vocal Waltari critic and ideological opponent Raoul Palmgren.

[74] When Finnish writer and scholar Panu Rajala [fi] was in 2017 asked by Ilta-Sanomat to select the 10 best books from Finland's period of independence, The Egyptian was one of them and he commented: "This is clear as day.