Enabling Act of 1933

Final solution Pre-Machtergreifung Post-Machtergreifung Parties The Enabling Act of 1933 (German: Ermächtigungsgesetz), officially titled Gesetz zur Behebung der Not von Volk und Reich (lit.

[3] Acting as chancellor, Hitler immediately accused the Communists of being the perpetrators of the fire and claimed the arson was part of a larger effort to overthrow the German government.

[5] As Hitler cleared the political arena of anyone willing to challenge him, he contended that the decree was insufficient, and required sweeping policies that would safeguard his emerging dictatorship.

The combined effect of the Enabling Act and the Reichstag Fire Decree transformed Hitler's government into a legal dictatorship and laid the groundwork for his totalitarian regime.

[15][16] By mid-March, the government began sending communists, trade union leaders, and other political dissidents to Dachau, the first Nazi concentration camp.

[17] The passing of the Enabling Act marked the formal transition from the democratic Weimar Republic to the totalitarian Nazi dictatorship.

Empowered by the Enabling Act, Hitler could begin German rearmament and achieve his aggressive foreign policy aims, which ultimately resulted in World War II.

The Enabling Act was renewed twice but was rendered moot when Nazi Germany surrendered to the Allies in 1945, and it was repealed by a law passed by the occupying powers in September of that year.

On 20 February 1933, at the official residence of Hermann Göring in the Reichstag Presidential Palace, a secret meeting was held, involving Hitler and 20 to 25 industrialists, aimed at financing the election campaign of the Nazi Party (NSDAP).

Hitler used the decree to have the office of the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) raided and its representatives arrested, effectively eliminating them as a political force.

Although they received five million more votes than in the previous election, the Nazis failed to gain an absolute majority in parliament, and depended on the 8% of seats won by their coalition partner, the German National People's Party (DNVP), to reach 52% in total.

Technically, even after the Enabling Act, the Weimar Constitution of 1919 remained in effect, only being nullified when Germany surrendered in 1945, at the end of World War II, and ceased to be a sovereign state.

The Enabling Act allowed the National Ministry (essentially the cabinet) to enact legislation, including laws deviating from or altering the constitution, without the consent of the Reichstag.

The Nazis expected the parties representing the middle class, the Junkers and business interests to vote for the measure, as they had grown weary of the instability of the Weimar Republic and would not dare to resist.

[20] Some historians, such as Klaus Scholder, have maintained that Hitler also promised to negotiate a Reichskonkordat with the Holy See, a treaty that formalized the position of the Catholic Church in Germany on a national level.

Pacelli had been pursuing a German concordat as a key policy for some years, but the instability of Weimar governments, as well as the opposition of some parties to a treaty, had blocked the project.

[21] The day after the Enabling Act vote, Kaas went to Rome in order to, in his own words, "investigate the possibilities for a comprehensive understanding between church and state".

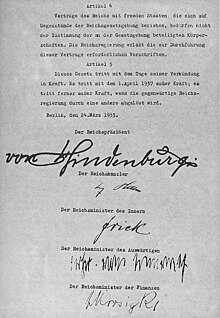

The full text, in German[23] and English, follows: Articles 1 and 4 gave the government the right to draw up the budget, approve treaties, and enact any laws whatsoever without input from the Reichstag.

[27] Hitler's speech, which emphasised the importance of Christianity in German culture, was aimed particularly at appeasing the Centre Party's sensibilities and incorporated Kaas' requested guarantees almost verbatim.

Kaas gave a speech, voicing his party's support for the bill amid "concerns put aside", while Brüning notably remained silent.

Only SPD chairman Otto Wels spoke against the Act, declaring that the proposed bill could not "destroy ideas which are eternal and indestructible".

With the KPD banned and 26 SPD deputies arrested or in hiding, the final tally was 444 in favour of the Enabling Act against 94 (all Social Democrats) opposed.

While the existence of the Reichstag was protected by the Enabling Act, for all intents and purposes it was reduced to a mere stage for Hitler's speeches.

In 1942, the Reichstag passed a law giving Hitler power of life and death over every citizen, effectively extending the provisions of the Enabling Act for the duration of the war.

The idea behind the concept is the notion that even a majority rule of the people cannot be allowed to install a totalitarian or autocratic regime such as with the Enabling Act of 1933, thereby violating the principles of the German constitution.

In his 2003 book, The Coming of the Third Reich, British historian Richard J. Evans argued that the Enabling Act was legally invalid.