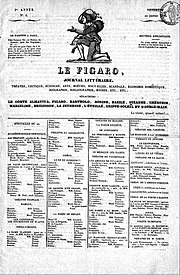

Le Figaro

It was named after Figaro, a character in a play by polymath Beaumarchais (1732–1799); one of his lines became the paper's motto: "Without the freedom to criticise, there is no flattering praise".

Its motto, from Figaro's monologue in the play's final act, is "Sans la liberté de blâmer, il n'est point d'éloge flatteur" ("Without the freedom to criticise, there is no flattering praise").

In 1833, editor Nestor Roqueplan fought a duel with a Colonel Gallois, who was offended by an article in Le Figaro, and was wounded but recovered.

[16] Albert Wolff, Émile Zola, Jean-Baptiste Alphonse Karr, Théophile Gautier, and Jules Arsène Arnaud Claretie were among the paper's early contributors.

On 20 February 1909 Le Figaro published a manifesto signed by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti which initiated the establishment of Futurism in art.

[29] In the 2010s, Le Figaro saw future presidential candidate Éric Zemmour's columns garner great interest among readers that would later serve to launch his political career.

[48] On April 13, 2015, Figaro Premium was launched, a paid offer (€9.90 per month initially, increasing to €15; free for newspaper subscribers).

It provided access to all articles from Le Figaro and its related magazines in a more comfortable reading format with minimal advertising, available from 10 p.m. the evening before the print publication.

[53] A study conducted in early 2020 by a cybersecurity company indicated that the personal data of the newspaper's website subscribers had been exposed on an unprotected server.

[54] In July 2021, the National Commission for Informatics and Liberties fined Le Figaro €50,000 for installing third-party cookies without users' consent, in violation of the GDPR.

[55] FigaroVox is an online section of figaro.fr created in 2014 by Alexis Brézet, a former journalist at Valeurs actuelles (from 1987 to 2000),[56] "holding a very right-wing line",[57] on the advice of Patrick Buisson,[58] a figure associated with Nicolas Sarkozy's shift to the far right in 2012.

[60] FigaroVox was led by Vincent Trémolet de Villers, who co-authored a book on La Manif pour tous (And France Awoke.

[56] Its contributors included Maxime Tandonnet, a former advisor on immigration to Nicolas Sarkozy, and Gilles-William Goldnadel, an attorney for Patrick Buisson.

[56] FigaroVox's preferred themes were "the decline of the republican school, poorly controlled immigration, and Islam as the primary threat to national identity".

[62] Political scientist Eszter Petronella suggested that FigaroVox allowed Le Figaro to "balance" the more moderate positions of the print daily by giving voice to an "identitarian and militant journalism," thereby catering to the needs of all readers.

[57] Information science specialist Aurélie Olivesi noted the proximity between the "polemical site" FigaroVox and the magazine Causeur, with some journalists having worked for both media.

[59] According to Nolwenn Le Blevennec, however, FigaroVox was haunted by an "identitarian obsession," exhibited an ultra-conservative and sovereignist editorial line, and remained a platform where one could read the National Front in the text, or link Islam and Daesh.

In 2020, the section had six regular columnists, Bertille Bayart, Nicolas Baverez, Renaud Girard, Mathieu Bock-Côté, Luc Ferry, Ivan Rioufol, along with guest contributors.

[71] In September 2010, it took over Adenclassifieds, following a friendly takeover bid; the subsidiary became Figaro Classifieds,[72] which included Cadremploi, Keljob.com, kelformation, kelstage, kelsalaire.net, CVmail, Explorimmo, CadresOnline, OpenMedia, Seminus, Microcode, achat-terrain.com.

In partnership with Dargaud Benelux, the newspaper launched in 2010 a 20-volume collection of XIII in a "prestige" edition[78] and a pre-publication of the latest volumes of the series throughout the summer of the same year in Le Figaro Magazine.

Additionally, the daily also offered a selection of comic books, from Largo Winch to Blake and Mortimer to Gaston, Tintin, Lucky Luke, and Spirou and Fantasio.