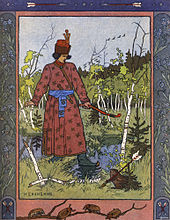

The Frog Princess

[2] Eastern European variants include the Frog Princess or Tsarevna Frog (Царевна Лягушка, Tsarevna Lyagushka)[3][4][5][6] and also Vasilisa the Wise (Василиса Премудрая, Vasilisa Premudraya); Alexander Afanasyev collected variants in his Narodnye russkie skazki, a collection which included folk tales from Ukraine and Belarus alongside Russian tales.

Another variation involves the sons chopping down trees and heading in the direction pointed by them in order to find their brides.

[8] In the Russian versions of the story, Prince Ivan and his two older brothers shoot arrows in different directions to find brides.

[15] According to researcher Carole G. Silver and Yolando Pino-Saavedra [es], apart from bird and fish maidens, local forms of the animal bride include a frog in Burma, Russia, Austria and Italy; a dog in India and in North America; a mouse in Sri Lanka;[16] the frog, the toad and the monkey in Iberian Peninsula, and in Spanish-speaking and Portuguese-speaking areas in the Americas.

[20] Likewise, scholar Maria Tatar describes the frog heroine as "resourceful, enterprising, and accomplished", whose amphibian skin is burned by her husband, and she has to depart to regions unknown.

[21] On the other hand, Barbara Fass Leavy draws attention to the role of the frog wife in female tasks, like cooking and weaving.

[24] Likewise, Russian scholarship (e.g., Vladimir Propp and Yeleazar Meletinsky) has argued for the totemic character of the frog princess.

[25] Charles Fillingham Coxwell [de] also associated these human-animal marriages to totem ancestry, and cited the Russian tale as one example of such.

[26] In his work about animal symbolism in Slavic culture, Russian philologist Aleksandr V. Gura [ru] stated that the frog and the toad are linked to female attributes, like magic and wisdom.

[27] In addition, according to ethnologist Ljubinko Radenkovich [sr], the frog and the toad represent liminal creatures that live between land and water realms, and are considered to be imbued with (often negative) magical properties in Slavic folklore.

[28] In some variants, the Frog Princess is the daughter of Koschei, the Deathless,[23] and Baba Yaga - sorcerous characters with immense magical power who appear in Slavic folklore in adversarial position.

[29] Georgios A. Megas noted two distinctive introductory episodes: the shooting of arrows appears in Greek, Slavic, Turkish, Finnish, Arabic and Indian variants, while following the feathers is a Western European occurrence.

[30] Likewise, Swedish scholar Waldemar Liungman [sv] located the motif of the arrow shooting in Slavic and Oriental variants, while the feather as the method of choice appears in Western European.

[31] Andrew Lang included an Italian variant of the tale, titled The Frog in The Violet Fairy Book.

[35] In a variant from northern Moldavia collected and published by Romanian author Elena Niculiță-Voronca, the bride selection contest replaces the feather and arrow for shooting bullets, and the frog bride commands the elements (the wind, the rain and the frost) to fulfill the three bridal tasks.

Later, the king asks his daughters-in-law to weave him a fine linen shirt and a beautiful carpet with gold, silver and silk, and finally to bake him delicious bread.

The maiden realizes her husband's folly and, saying her name is Vasilisa the Wise, tells him she will vanish to a distant kingdom and begs him to find her.

[38] In a Czech variant translated by Jeremiah Curtin, The Mouse-Hole, and the Underground Kingdom, prince Yarmil and his brothers are to seek wives and bring to the king their presents in a year and a day.

The prince enters the mouse hole, finds a splendid castle and an ugly toad he must bathe for a year and a day.

When she comes home, she reveals the prince her cursed state would soon be over, says he needs to find Baba Yaga in a remote kingdom, and vanishes from sight in the form of a cuckoo.

[41] Finnish author Eero Salmelainen [fi] collected a Finnish tale with the title Sammakko morsiamena (English: "The Frog Bride"), and translated into French as Le Cendrillon et sa fiancée, la grenouille ("The Male Cinderella and his bride, the frog").

In this tale, a king has three sons, the youngest named Tuhkimo (a male Cinderella; from Finnish tuhka, "ashes").

[42][43] In the Azerbaijani version of the fairy tale, the princes do not shoot arrows to choose their fiancées, they hit girls with apples.

One day, the elder two decide to leave home to learn a trade and find wives, and their foolish little brother wants to do so.

The little frog tells Hans to sleep and, in the next morning, to knock three times on the stable door with a wand; he will find a beautiful horse he can ride home, and a little box.

Hans goes back home with the horse and gives the little box to his mother; inside, a beautiful dress of gold and diamond buttons.

The prince questions the frog's decision, but she advises him to tell his family he married an Eastern lady who must be only seen by her beloved.

He follows footprints and enters a grass-hut where he meets a talking frog who tells him to prepare for their wedding, for, when she comes, the earth will tremble and the skies will thunder, but he has nothing to fear.

The three princess convene back in with their father, who asks his sons for their wives first to bring the best bread they can bake, and the best shirts they can weave.

The Torem khan's daughters-in-law fulfill his requests, and he does approve of their efforts, but lauds the youngest's bride's work.