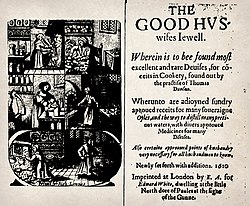

The Good Huswifes Jewell

The book includes recipes still current, such as pancakes, haggis, and salad of leaves and flowers with vinaigrette sauce, as well as some not often made, such as mortis, a sweet chicken pâté.

Cookery was changing as trade brought new ingredients, and fashion favoured new styles of cooking, with, for example, locally grown herbs as well as imported spices.

For stuffing for meat and poultry, or as Dawson says "to farse all things", he recommends using the herbs thyme, hyssop, and parsley, mixed with egg yolk, white bread, raisins or barberries, and spices including cloves, mace, cinnamon and ginger, all in the same dish.

[9] The recipe for a salad with a vinaigrette dressing runs as follows (from the 1596 edition):[10] To Make a Sallet of All Kinde of HearbesTake your hearbes and picke them very fine into faire water, and picke your flowers by themselues, and washe them al cleane, and swing them in a strainer, and when you put them into a dish, mingle them with Cowcumbers or Lemmons payred and sliced, and scrape Suger, and put in vineger and Oyle, and throwe the flowers on the toppe of the sallet, and of every sorte of the aforesaide things and garnish the dish about with the foresaide things, and harde Egges boyled and laide about the dish and upon the sallet.This recipe is taken up by the National Trust, which calls it "Stourhead herb and flower salad.

The celebrity chef Clarissa Dickson Wright comments on Dawson's trifle that it differs from the modern recipe, as it consists only of "a pinte of thicke Creame", seasoned with sugar, ginger and rosewater, and warmed gently for serving.

[15] She notes, also from the Good Huswife's Jewell, that the Elizabethans had a strong liking for sweet things, "richly demonstrated" in Dawson's "names of all things necessary for a banquet":[16] Sugar, cinnamon, liquorice, pepper, nutmegs, all kinds of saffron, sanders, comfits, aniseeds, coriander, oranges, pomegranate seeds, Damask water, turnsole, lemons, prunes, rose water, dates, currants, raisins, cherries conserved, barberries conserved, rye flower, ginger, sweet oranges, pepper white and brown, mace, wafers.

[17] The culinary historian Ken Albala describes the Jewell as an "important cookbook", and observes that it is the first English cookery book to give a recipe for sweet potatoes (which had arrived in Europe after Columbus's voyages), while also listing "old medieval standbys".

It, like Gervase Markham's The English Huswife of 1615, was aimed at a more general audience, not only aristocrats but "housewives", which Mennell glosses as "gentlewomen concerned with the practical tasks of running households".