The Heart of the Andes

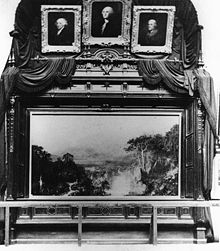

The exhibition rooms featured special lighting and decorative elements reminiscent of the depicted landscape, and the painting was supported by a floor-standing frame.

The snow-capped Mount Chimborazo of Ecuador appears in the distance; the viewer's eye is led to it by the darker, closer slopes that decline from right to left.

The evidence of human presence is shown by the lightly worn path, a hamlet and church lying in the central plain, and closer to the foreground, two locals are seen before a cross.

The play of light on his signature has been interpreted as the artist's statement of man's ability to tame nature—yet the tree appears in poor health compared to the vivid jungle surrounding it.

[5] Church's landscape conformed to the aesthetic principles of the picturesque, as propounded by the British theorist William Gilpin, which began with a careful observation of nature enhanced by particular notions about composition and harmony.

The juxtaposition of smooth and irregular forms was an important principle, and is represented in The Heart of the Andes by the rounded hills and pool of water on the one hand, and by the contrasting jagged mountains and rough trees on the other.

Following this theme, the painting displays the landscape in detail at all scales, from the intricate foliage, birds, and butterflies in the foreground to the all-encompassing portrayal of the natural environments studied by Church.

The event attracted an unprecedented turnout for a single-painting exhibition in the United States: more than 12,000 people paid an admission fee of twenty-five cents to view the painting.

A skylight directed at the canvas heightened the perception that the painting was illuminated from within, as did the dark fabrics draped on the studio walls to absorb light.

An excerpt from Noble reads: Imagine yourself, late in the afternoon with the sun behind you, to be travelling up the valley along the bank of a river, at an elevation above the hot country of some five or six thousand feet.

At the point to which you have ascended, heavily-wooded mountains close in on either hand, (not visible in the picture – only the foot of each jutting into view,) richly clothed with trees and all the appendage of the forest, with the river flowing between them.

Conspicuous on the opposite side of the river is the road leading into the country above, a wild bridle-path in the brightest sunshine, winding up into, and losing itself in the thick shady woods.

Close to the end of the first exhibition, on May 9, 1859, he wrote of this desire to American poet Bayard Taylor: The "Andes" will probably be on its way to Europe before your return to the City ... [The] principal motive in taking the picture to Berlin is to have the satisfaction of placing before Humboldt a transcript of the scenery which delighted his eyes sixty years ago—and which he had pronounced to be the finest in the world.

While the painting was in London, Church's agent arranged to have an engraving of it made by Charles Day & Son, which would allow for broad distribution of reproductions and hence more income.

We took the opera glass, and examined its beauties minutely, for the naked eye cannot discern the little wayside flowers, and soft shadows and patches of sunshine, and half-hidden bunches of grass and jets of water which form some of its most enchanting features.

[14]The New York Times described the painting's "harmony of design" and "chaos of chords or colors gradually rises upon the enchanted mind a rich and orderly creation, full of familiar objects, yet wholly new in its combinations and its significance.