Hebrides

[1] The Hebrides have a diverse geology, ranging in age from Precambrian strata that are amongst the oldest rocks in Europe, to Paleogene igneous intrusions.

[2][3][Note 1] Raised shore platforms in the Hebrides have been identified as strandflats, possibly formed during the Pliocene period and later modified by the Quaternary glaciations.

The Inner Hebrides lie closer to mainland Scotland and include Islay, Jura, Skye, Mull, Raasay, Staffa and the Small Isles.

The Outer Hebrides form a chain of more than 100 islands and small skerries located about 70 km (45 mi) west of mainland Scotland.

[Note 2] The Hebrides have a cool, temperate climate that is remarkably mild and steady for such a northerly latitude, due to the influence of the Gulf Stream.

About 80 years after Pliny the Elder, in 140–150 AD, Ptolemy (drawing on accounts of the naval expeditions of Agricola) writes that there are five Ebudes (possibly meaning the Inner Hebrides) and Dumna.

[11] Ptolemy calls Islay "Epidion",[13] and the use of the letter "p" suggests a Brythonic or Pictish tribal name, Epidii,[14] because the root is not Gaelic.

[15] Woolf (2012) has suggested that Ebudes may be "an Irish attempt to reproduce the word Epidii phonetically, rather than by translating it", and that the tribe's name may come from the root epos, meaning "horse".

In relation to Dubh Artach, Robert Louis Stevenson believed that "black and dismal" was one translation of the name, noting that "as usual, in Gaelic, it is not the only one.

[100][101] In 55 BC, the Greek historian Diodorus Siculus wrote that there was an island called Hyperborea (which means "beyond the North Wind"), where a round temple stood from which the moon appeared only a little distance above the earth every 19 years.

[105] The figure of Columba looms large in any history of Dál Riata, and his founding of a monastery on Iona ensured that the kingdom would be of great importance in the spread of Christianity in northern Britain.

Lismore in the territory of the Cenél Loairn, was sufficiently important for the death of its abbots to be recorded with some frequency and many smaller sites, such as on Eigg, Hinba, and Tiree, are known from the annals.

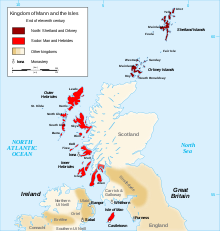

"[107] Viking raids began on Scottish shores towards the end of the 8th century, and the Hebrides came under Norse control and settlement during the ensuing decades, especially following the success of Harald Fairhair at the Battle of Hafrsfjord in 872.

[108][109] In the Western Isles Ketill Flatnose may have been the dominant figure of the mid 9th century, by which time he had amassed a substantial island realm and made a variety of alliances with other Norse leaders.

His skald Bjorn Cripplehand recorded that in Lewis "fire played high in the heaven" as "flame spouted from the houses" and that in the Uists "the king dyed his sword red in blood".

[113] Following the ill-fated 1263 expedition of Haakon IV of Norway, the Outer Hebrides and the Isle of Man were yielded to the Kingdom of Scotland as a result of the 1266 Treaty of Perth.

[112][116][Note 6] This transition did little to relieve the islands of internecine strife although by the early 14th century the MacDonald Lords of the Isles, based on Islay, were in theory these chiefs' feudal superiors and managed to exert some control.

[128] The British government's strategy was to estrange the clan chiefs from their kinsmen and turn their descendants into English-speaking landlords whose main concern was the revenues their estates brought rather than the welfare of those who lived on them.

Roads and quays were built; the slate industry became a significant employer on Easdale and surrounding islands; and the construction of the Crinan and Caledonian canals and other engineering works such as Clachan Bridge improved transport and access.

[131] However, in the mid-19th century, the inhabitants of many parts of the Hebrides were devastated by the Clearances, which destroyed communities throughout the Highlands and Islands as the human populations were evicted and replaced with sheep farms.

[132] The position was exacerbated by the failure of the islands' kelp industry that thrived from the 18th century until the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815[133][134] and large scale emigration became endemic.

[135] As Iain Mac Fhearchair, a Gaelic poet from South Uist, wrote for his countrymen who were obliged to leave the Hebrides in the late 18th century, emigration was the only alternative to "sinking into slavery" as the Gaels had been unfairly dispossessed by rapacious landlords.

[1] The discovery of substantial deposits of North Sea oil in 1965 and the renewables sector have contributed to a degree of economic stability in recent decades.

This tradition includes many songs composed by little-known or anonymous poets, well-before the 1800s, such as "Fear a' bhàta", "Ailein duinn", "Hùg air a' bhonaid mhòir" and "Alasdair mhic Cholla Ghasda".

Their instruments have been played by musicians such as Mairead Nesbitt, Cora Smyth and Eileen Ivers, and have been featured in productions such as Michael Flatley's Lord of the Dance, Feet of Flames, and Riverdance.

[160] Allan MacDonald (1859–1905), who spent his adult life on Eriskay and South Uist, composed hymns and verse in honour of the Blessed Virgin, the Christ Child, and the Eucharist.

In his verse drama, Parlamaid nan Cailleach (The Old Wives' Parliament), he lampooned the gossiping of his female parishioners and local marriage customs.

[161] In the 20th century, Murdo Macfarlane of Lewis wrote Cànan nan Gàidheal, a well-known poem about the Gaelic revival in the Outer Hebrides.

[162] Sorley MacLean, the most respected 20th-century Gaelic writer, was born and raised on Raasay, where he set his best known poem, Hallaig, about the devastating effect of the Highland Clearances.

[194][195] Hedgehogs are not native to the Outer Hebrides—they were introduced in the 1970s to reduce garden pests—and their spread poses a threat to the eggs of ground nesting wading birds.