LZ 129 Hindenburg

The airship flew from March 1936 until it was destroyed by fire 14 months later on May 6, 1937, while attempting to land at Lakehurst Naval Air Station in Manchester Township, New Jersey, at the end of the first North American transatlantic journey of its second season of service.

The delay was largely due to Daimler-Benz designing and refining the LOF-6 diesel engines to reduce weight while fulfilling the output requirements set by the Zeppelin Company.

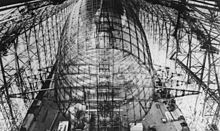

[4] Hindenburg had a duralumin structure, incorporating 15 Ferris wheel-like main ring bulkheads along its length, with 16 cotton gas bags fitted between them.

The airship's outer skin was of cotton doped with a mixture of reflective materials intended to protect the gas bags within from radiation, both ultraviolet (which would damage them) and infrared (which might cause them to overheat).

At the time, however, helium was also relatively rare and extremely expensive as the gas was available in industrial quantities only from distillation plants at certain oil fields in the United States.

Four years after construction began in 1932, Hindenburg made its maiden test flight from the Zeppelin dockyards at Friedrichshafen on March 4, 1936, with 87 passengers and crew aboard.

As the airship passed over Munich on its second trial flight the next afternoon, the city's Lord Mayor, Karl Fiehler, asked Eckener by radio the LZ129's name, to which he replied "Hindenburg".

[17] The name Hindenburg lettered in 1.8-metre (5 ft 11 in) high red Fraktur script (designed by Berlin advertiser Georg Wagner) was added to its hull three weeks later before the Deutschlandfahrt on March 26.

[20] This was to be followed by its first commercial passenger flight, a four-day transatlantic voyage to Rio de Janeiro that departed from the Friedrichshafen Airport in nearby Löwenthal on March 31.

[25] On March 7, 1936, ground forces of the German Reich had entered and occupied the Rhineland, a region bordering France, which had been designated in the 1919 Treaty of Versailles as a de-militarized zone established to provide a buffer between Germany and that neighboring country.

According to American reporter William L. Shirer, "Hugo Eckener, who is getting [the Hindenburg] ready for its maiden flight to Brazil, strenuously objected to putting it in the air this weekend on the ground it was not fully tested, but Dr. Goebbels insisted.

As the massive airship began to rise under full engine power she was caught by a 35-degree crosswind gust, causing her lower vertical tail fin to strike and be dragged across the ground, resulting in significant damage to the bottom portion of the airfoil and its attached rudder.

[32] Graf Zeppelin, which had been hovering above the airfield waiting for Hindenburg to join it, had to start off on the propaganda mission alone while LZ 129 returned to her hangar.

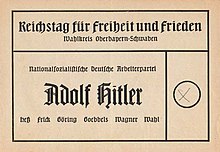

[33] As millions of Germans watched from below, the two giants of the sky sailed over Germany for the next four days and three nights, dropping propaganda leaflets, blaring martial music and slogans from large loudspeakers, and broadcasting political speeches from a makeshift radio studio aboard Hindenburg.

"[40] This action was taken because of Eckener's opposition to using Hindenburg and Graf Zeppelin for political purposes during the Deutschlandfahrt, and his "refusal to give a special appeal during the Reichstag election campaign endorsing Chancellor Adolf Hitler and his policies.

Unexpectedly, the crew found such a wind at the lower altitude of 1,100 metres (3,600 ft) which permitted them to guide the airship safely back to Germany after gaining emergency permission from France to fly a more direct route over the Rhone Valley.

Two boys, Alfred Butler and Jack Gerrard, retrieved it and found the contents to be a bouquet of carnations, a small silver cross and a letter on official note paper dated May 22, 1936.

[50] In July 1936, Hindenburg completed a record Atlantic round trip between Frankfurt and Lakehurst in 98 hours and 28 minutes of flight time (52:49 westbound, 45:39 eastbound).

[51] Many prominent people were passengers on the Hindenburg, including boxer Max Schmeling making his triumphant return to Germany in June 1936 after his world heavyweight title knockout of Joe Louis at Yankee Stadium.

A one-way fare between Germany and the United States was US$400 (equivalent to $8,783 in 2023); Hindenburg passengers were affluent, usually entertainers, noted sportsmen, political figures, and leaders of industry.

Shortly before the arrival of Adolf Hitler to declare the Games open, the airship crossed low over the packed stadium while trailing the Olympic flag on a long weighted line suspended from its gondola.

Ambassador to the United Kingdom Winthrop W. Aldrich, his 28-year-old nephew Nelson Rockefeller, who became the Governor of New York and, later, Vice President of the United States, various German and American government officials and military officers, as well as key figures in the aviation industry, including Juan Trippe, founder and Chief Executive of Pan American Airways, and World War I flying ace Captain Eddie Rickenbacker, president of Eastern Airlines.

The ship arrived at Boston by noon and returned to Lakehurst at 5:22 pm before making its final transatlantic flight of the season back to Frankfurt.

This was intended to allow customs officials to be flown out to Hindenburg to process passengers before landing and to retrieve mail from the ship for early delivery.

Experimental hook-ons and takeoffs, piloted by Ernst Udet, were attempted on March 11 and April 27, 1937, but were not very successful, owing to turbulence around the hook-up trapeze.

[63] Hindenburg's arrival on 6 May was delayed for several hours to avoid a line of thunderstorms passing over Lakehurst, but around 7:00 pm the airship was cleared for its final approach to the Naval Air Station, which it made at an altitude of 200 m (660 ft) with Captain Max Pruss in command.

Manually controlled and automatic valves for releasing hydrogen were located partway up one-meter diameter ventilation shafts that ran vertically through the airship.

[70] The high static charge collected from flying within stormy conditions and inadequate grounding of the outer envelope to the frame could have ignited any resulting gas-air mixture at the top of the airship.

[71] In support of the hypothesis that hydrogen was leaking from the aft portion of the Hindenburg prior to the conflagration, water ballast was released at the rear of the airship and six crew members were dispatched to the bow to keep the craft level.