The Man in the Moone

On his voyage home he becomes seriously ill, and he and a negro servant Diego are put ashore on St Helena, a remote island with a reputation for "temperate and healthful" air.

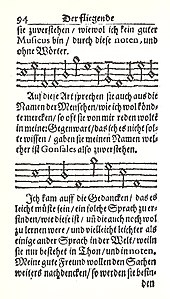

Gonsales gradually comes to realise that these birds are able to carry substantial burdens, and resolves to construct a device by which a number of them harnessed together might be able to support the weight of a man, allowing him to move around the island more conveniently.

[6] But on his way back to Spain, accompanied by his birds and the device he calls his Engine, his ship is attacked by an English fleet off the coast of Tenerife and he is forced to escape by taking to the air.

[7] They provide him with food and drink for his journey and promise to set him down safely in Spain if only he will join their "Fraternity", and "enter into such Covenants as they had made to their Captain and Master, whom they would not name".

Suddenly feeling very hungry he opens the provisions he was given en route, only to find nothing but dry leaves, goat's hair and animal dung, and that his wine "stunk like Horse-piss".

[9] He is soon discovered by the inhabitants of the Moon, the Lunars, whom he finds to be tall Christian people enjoying a happy and carefree life in a kind of pastoral paradise.

Fearing that he may never be able to return to Earth and see his children again if he delays further, he decides to take leave of his hosts, carrying with him a gift of precious stones from the supreme monarch of the Moon, Irdonozur.

The story ends with Gonsales's fervent wish that he may one day be allowed to return to Spain, and "that by enriching my country with the knowledge of these hidden mysteries, I may at least reap the glory of my fortunate misfortunes".

He gained prominence (even internationally) in 1601 by publishing his Catalogue of the Bishops of England since the first planting of the Christian Religion in this Island, which enabled his rapid rise in the church hierarchy.

[19] Godwin's book appeared in a time of great interest in the Moon and astronomical phenomena, and of important developments in celestial observation, mathematics and mechanics.

[1] Galileo Galilei's 1610 publication Sidereus Nuncius (usually translated as "The Sidereal Messenger") had a great influence on Godwin's astronomical theories, although Godwin proposes (unlike Galileo) that the dark spots on the Moon are seas, one of many similarities between The Man in the Moone and Kepler's Somnium sive opus posthumum de astronomia lunaris of 1634 ("The Dream, or Posthumous Work on Lunar Astronomy").

And Godwin seems to borrow the concept of using a flock of strong, trained birds to fly Gonsales to the Moon from Francis Bacon's Sylva sylvarum ("Natural History"), published in July 1626.

[23] Poole also sees the influence of Robert Burton, who in the second volume of The Anatomy of Melancholy had speculated on gaining astronomical knowledge through telescopic observation (citing Galileo) or from space travel (Lucian).

Details pertaining to the sea voyage and Saint Helena likely came from Thomas Cavendish's account of his circumnavigation of the world, available in Richard Hakluyt's Principal Navigations (1599–1600) and in Purchas His Pilgrimage, first published in 1613.

[30] H. W. Lawton's review published six years earlier mentions a second copy in the Bibliothèque nationale de France, V.20973 (now RES P- V- 752 (6)), an omission also noted by Tillotson.

[31] The printer of the first edition of The Man in the Moone is identified on the title page as John Norton, and the book was sold by Joshua Kirton and Thomas Warren.

[37] Beginning in the 1580s, when Godwin was a student at Oxford University, many publications criticising the governance of the established Church of England circulated widely, until in 1586 censorship was introduced, resulting in the Martin Marprelate controversy.

A number of commentators, including Grant McColley, have suggested that Godwin strongly objected to the imposition of censorship, expressed in Gonsales's hope that the publication of his account may not prove "prejudicial to the Catholic faith".

In contrast with Clark and Poole, David Cressy argues that the Lunars falling to their knees after Gonsales's exclamation (a similar ritual takes place at the court of Irdonozur) is evidence of "a fairly mechanical form of religion (as most of Godwin's Protestant contemporaries judged Roman Catholicism)".

Midway through the 17th century the matter appears to have been settled in favour of a possible plurality, which was accepted by Henry More and Aphra Behn among others; "by 1650, the Elizabethan Oxford examination question an sint plures mundi?

Invented languages were an important element of earlier fantastical accounts such as Thomas More's Utopia, François Rabelais's Gargantua and Pantagruel and Joseph Hall's Mundus Alter et Idem, all books that Godwin was familiar with.

Thus the mandarins are able to maintain a cultural and spiritual superiority resembling that of the Lunar upper class, which is to be placed in contrast with the variety of languages spoken in a fractured and morally degenerate Europe and elsewhere.

[22] He suggests Godwin's source may have been a book by Joan Baptista Porta, whose De occultis literarum notis (1606)[j] contains "an exact description of the method he was to adopt".

[55] Godwin's book follows a venerable tradition of travel literature that blends the excitement of journeys to foreign places with utopian reflection; More's Utopia is cited as a forerunner, as is the account of Amerigo Vespucci.

Godwin could fall back on an extensive body of work describing the voyages undertaken by his protagonist, including books by Hakluyt and Jan Huyghen van Linschoten, and the narratives deriving from the Jesuit mission in Beijing.

[16] In the third edition of The Discovery (1640), however, Wilkins provides a summary of Godwin's book, and later in Mercury (1641) he comments on The Man in the Moone and Nuncius Inanimatus, saying that "the former text could be used to unlock the secrets of the latter".

[60] It was one of the inspirations for what has been called the first science fiction text in the Americas, Syzygies and Lunar Quadratures Aligned to the Meridian of Mérida of the Yucatán by an Anctitone or Inhabitant of the Moon ... by Manuel Antonio de Rivas (1775).

The Oxford English Dictionary's entry for gansa reads "One of the birds (called elsewhere 'wild swans') which drew Domingo Gonsales to the Moon in the romance by Bp.