Natural History (Pliny)

The largest single work to have survived from the Roman Empire to the modern day, the Natural History compiles information gleaned from other ancient authors.

These cover topics including astronomy, mathematics, geography, ethnography, anthropology, human physiology, zoology, botany, agriculture, horticulture, pharmacology, mining, mineralogy, sculpture, art, and precious stones.

Pliny's Natural History became a model for later encyclopedias and scholarly works as a result of its breadth of subject matter, its referencing of original authors, and its index.

[3] Pliny claims to be the only Roman ever to have undertaken such a work, in his prayer for the blessing of the universal mother:[4][5] Hail to thee, Nature, thou parent of all things!

After an initial survey of cosmology and geography, Pliny starts his treatment of animals with the human race, "for whose sake great Nature appears to have created all other things".

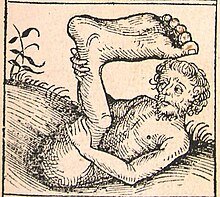

[a] These monstrous races – the Cynocephali or Dog-Heads, the Sciapodae, whose single foot could act as a sunshade, the mouthless Astomi, who lived on scents – were not strictly new.

They had been mentioned in the fifth century BC by Greek historian Herodotus (whose history was a broad mixture of myths, legends, and facts), but Pliny made them better known.

Moreover, the path is not a beaten highway of authorship, nor one in which the mind is eager to range: there is not one of us who has made the same venture, nor yet one among the Greeks who has tackled single-handed all departments of the subject.Pliny studied the original authorities on each subject and took care to make excerpts from their pages.

In the geographical books, Varro is supplemented by the topographical commentaries of Agrippa, which were completed by the emperor Augustus; for his zoology, he relies largely on Aristotle and on Juba, the scholarly Mauretanian king, studiorum claritate memorabilior quam regno (v.

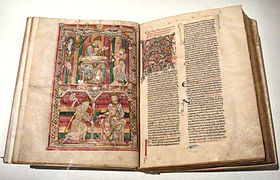

[4] Early in the 8th century, Bede, who admired Pliny's work, had access to a partial manuscript which he used in his "De natura rerum", especially the sections on meteorology and gems.

6795): Possible descendants of E: Copies of E: Cousin of E: Independent earlier tradition: The work was one of the first classical manuscripts to be printed, at Venice in 1469 by Johann and Wendelin of Speyer, but J.F.

Pliny starts with the known universe, roundly criticising attempts at cosmology as madness, including the view that there are countless other worlds than the Earth.

[55] Book II continues with natural meteorological events lower in the sky, including the winds, weather, whirlwinds, lightning, and rainbows.

[62] Domestic dogs, horses, and livestock feature prominently, with elaboration on their uses to humans, for example the types of wool produced by sheep and the cloth created from them.

The keeping of aquariums was a popular pastime of the rich, and Pliny provides anecdotes of the problems of owners becoming too closely attached to their fish.

As well, the silkworm and silk production are described, the discovery of which is attributed to a woman named Pamphile (no reference is made to China).

Evidence cited includes the fact that some samples exhibit encapsulated insects, a feature readily explained by the presence of a viscous resin.

A major section of the Natural History, Books XX to XXIX, discusses matters related to medicine, especially plants that yield useful drugs.

For example, he describes a simple mechanical reaper that cut the ears of wheat and barley without the straw and was pushed by oxen (Book XVIII, chapter 72).

He gives examples of the way rulers proclaimed their prowess by exhibiting gold looted from their campaigns, such as that by Claudius after conquering Britain, and tells the stories of Midas and Croesus.

He once saw Agrippina the Younger, wife of Claudius, at a public show on the Fucine Lake involving a naval battle, wearing a military cloak made of gold.

Britain, he says, is very rich in lead, which is found on the surface at many places, and thus very easy to extract; production was so high that a law was passed attempting to restrict mining.

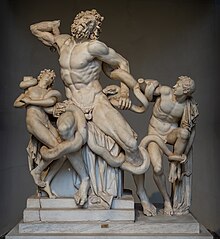

The anecdotic element has been ascribed to Duris (XXXIV:61); the notices of the successive developments of art and the list of workers in bronze and painters to Xenocrates; and a large amount of miscellaneous information to Antigonus.

[4] For a number of items relating to works of art near the coast of Asia Minor and in the adjacent islands, Pliny was indebted to the general, statesman, orator and historian Gaius Licinius Mucianus, who died before 77.

The main merit of his account of ancient art, the only classical work of its kind, is that it is a compilation ultimately founded on the lost textbooks of Xenocrates and on the biographies of Duris and Antigonus.

[i] Pliny was scathing about the search for precious metals and gemstones: "Gangadia or quartzite is considered the hardest of all things – except for the greed for gold, which is even more stubborn.

[92] The anonymous fourth-century compilation Medicina Plinii contains more than 1,100 pharmacological recipes, the vast majority of them from the Historia naturalis; perhaps because Pliny's name was attached to it, it enjoyed huge popularity in the Middle Ages.

For example, one twentieth-century historian has argued that Pliny's reliance on book-based knowledge, and not direct observation, shaped intellectual life to the degree that it "stymie[d] the progress of western science".

Wherein notwithstanding the credulity of the Reader is more condemnable then the curiosity of the Author: for commonly he nameth the Authors from whom he received those accounts, and writes but as he reads, as in his Preface to Vespasian he acknowledgeth.Grundy Steiner of Northwestern University, in a 1955 judgement considered by Thomas R. Laehn to represent the collective opinion of Pliny's critics,[101] wrote of Pliny that "He was not an original, creative thinker, nor a pioneer of research to be compared either with Aristotle and Theophrastus or with any of the great moderns.

[104] In the view of Mary Beagon, writing in The Classical Tradition in 2010:the Historia naturalis has regained its status to a greater extent than at any time since the advent of Humanism.