The Masses

The Masses was a graphically innovative American magazine of socialist politics published monthly from 1911 until 1917, when federal prosecutors brought charges against its editors for conspiring to obstruct conscription in the United States during World War I.

It published reportage, fiction, poetry and art by the leading radicals of the time such as Max Eastman, John Reed, Dorothy Day, and Floyd Dell.

For the first year of its publication, the printing and engraving costs of the magazine were paid for by a sympathetic patron, Rufus Weeks, a vice president at the New York Life Insurance Company.

His vision of an illustrated socialist monthly had, however, attracted a circle of young activists in Greenwich Village to The Masses; these included visual artists such as John French Sloan from the Ashcan School.

These Greenwich Village artists and writers asked one of their own, Max Eastman (who was then studying for a doctorate under John Dewey at Columbia University), to edit their magazine.

John Sloan, Art Young, Louis Untermeyer, and Inez Haynes Gillmore (among others) mailed a terse letter to Eastman in August 1912: "You are elected editor of The Masses.

"[4] The Masses was very much embedded in a specific metropolitan milieu, unlike some other competing socialist periodicals (such as the Appeal to Reason, a populist-inflected 500,000-circulation weekly produced out of Girard, Kansas).

Rand followed up by persuading the District Attorney in New York City to convene a Grand Jury, which indicted Eastman and Young for criminal libel in December 1913.

[9][11] Young and Eastman were represented pro bono by Gilbert Roe, and their plight attracted the support of an array of activists including Lincoln Steffens, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Inez Milholland, and Amos Pinchot.

The AP demanded he retract his statement on the threat of a $150,000 libel lawsuit, but Pinchot persuaded the organization that the publicity would reflect poorly on them and the suit went nowhere.

The business manager, Merrill Rogers, "made efforts to be in compliance by seeking counsel from George Creel, Chairman of the Committee on Public Post office still denied use of the mails.

Charged with seeking to "unlawfully and willfully…obstruct the recruiting and enlistment of the United States" military, Eastman and his "conspirators" faced fines up to 10,000 dollars and twenty years imprisonment.

Prior to releasing the jurors, Judge Hand stated, "I do not have to remind you that every man has the right to have such economic, philosophic or religious opinions as seem to him best, whether they be socialist, anarchistic or atheistic.

It strongly sympathized with Big Bill Haywood and his IWW, the political campaigns of Eugene V. Debs, and a variety of other socialist and anarchist figures.

Several of its Greenwich Village contributors, like Reed and Dell, practiced free love in their spare time and promoted it (sometimes in veiled terms) in their pieces.

Support for these social reforms was sometimes controversial within Marxist circles at the time; some argued that they were distractions from a more proper political goal, class revolution.

Anderson was "discovered" by The Masses' fiction editor, Floyd Dell, and his pieces there formed the foundation for his Winesburg, Ohio stories.

Dell's perceptive reviews gave accolades to many of the most notable books of the time: An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution, Spoon River Anthology, Theodore Dreiser's novels, Carl Jung's Psychology of the Unconscious, G. K. Chesterton's works, Jack London's memoirs, and many other prominent creations.

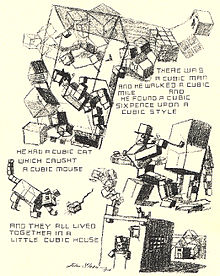

Although the magazine's birth coincided with the explosion of modernism, and its contributor Arthur B. Davies was an organizer of the Armory Show, The Masses published for the most part realist artwork that would later be classified in the Ashcan School.

This technique resulted in "capturing the feeling of a rapid sketch made on the spot and permitting a direct, unmediated response to what they saw"[18] and is commonly found on the pages of The Masses from 1912 to 1916.

This particularly irritated John Sloan who saw the magazine as moving away from its original purpose and stated, "The Masses is no longer the resultant of the ideas and art of a number of personalities.

The cartoons, especially those by Young and Minor, were at times quite controversial and, after the United States entered World War I, considered treasonous for their anti-war sentiments.