The Monastery of Love

In terms of content, the special feature of the work in comparison to other narrative Minnerede and Minneallegories is that it avoids personifications, meaning, for example, that Lady Love (Frau Minne) does not appear as a woman.

The manuscript has a total of 79 pages and contains 35 smaller poetic texts, such as fairy tales, prayers, love letters and Minnereden, including the Minnelehre of Johann von Konstanz.

It was written in the North Alemannic-South Franconian dialect, which is why today the Upper Rhine region is assumed to be the origin of the scribe.

The woman tells him she is traveling as a messenger of the werdi Minne (Lady Love) who, as a noble queen, has power over all the lands of the earth.

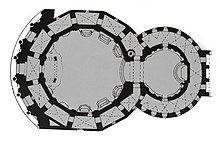

After asking again, the rider reveals further details: a (master) builder has created a unique, huge monastery in which Love lives.

Anyone who enters the monastery will have a wonderful life and people from all social classes will go there: kings, dukes, counts, maids, knights and servants.

Mockers, envious, fickle and cowardly people are also in the monastery prison, but the narrator decides to return with his companion to the other women and watch the tournament.

His acquaintance tells him that Love herself is invisible and can only be seen in all her effects among the men and women of the monastery, but the narrator refuses to believe her.

"[12] The Monastery of Love belongs to the literary genre of so-called Minnereden, which was mainly popular in the late Middle Ages and can also be described as a love-allegory.

The text is a Minnerede because it treats the topic of courtly love (in Middle High German, Minne) in a didactic or instructive manner for long stretches.

"The actual allegory is missing in so far as not only none of the otherwise popular personifications such as honor, shame, stature, dignity, confidence and the like, but also "love" herself, the much-mentioned one, does not appear in person.

[19] Richter refers to "an older conception"[20] that defines Love as a ghostly, invisible being, as is the case, for example, in the didactic poem Die Winsbekin, in which the daughter asks her mother: nu sage mir ob diu Minne lebe / und hie bî uns ûf erde sî / od ob uns in den lüften swebe, to which the mother replies, referring to Ovid, that si vert unsictic als ein geist.

This almost corresponds to the distance from the Arctic Circle to the equator or from Gibraltar in the west to India in the east, i.e. the area of the entire known orbis terrarum of the 14th century.

"[24] Wolfgang Achnitz 2006The monastery should therefore not be understood as a real building, but rather as an allegorical reference to Love's domain, which is also mentioned in the text itself: sie hat gewalt über alli lant[25] and, with regard to the simultaneously existing seasons, also at all times.

[26] The size of the monastery and the climatic peculiarities are mentioned in the work at the beginning, "but not developed to full vividness"[27] and no longer play a role in the further course of the plot.

[28] The motif of the allegorical monastery can already be found in medieval Latin poetry, for example in Hugh of Fouilloy's work De claustro animae from 1160.

[31] "But otherwise the poem - in contrast to Hadamar von Laber's allegorical love doctrine, which was written around the same time - has hardly had any discernible effect.

"[35] The author makes use of rhetorical stylistic devices such as word clusters and parallelisms, but the weakness of the text is the uniformity of expression.

Nevertheless, Laßberg, for example, considered The Monastery of Love to be the most beautiful poem in his Liedersaal, which can be explained, among other things, by the vividness of the narrative: "Again and again, the opportunity is taken to create something unmistakable through the detailed, imaginative shaping of a scene or situation, not just to vary topoi once again.

[19] As both the author and the date of composition are not clear from the work itself, the Minnerede The Monastery of Love offers room for interpretation and speculation.

Since the "rediscovery" of the work in the course of its publication by Joseph von Laßberg, there have been repeated attempts to determine the time of composition and the author more precisely.

On the one hand, the secular knightly society of the Order of the Lion left no traces in the political sphere of the spiritual knightly order of the Monastery of Minne; on the other hand, the lion and panther are common medieval heraldic animals, so that a mere similarity of the society's insignia cannot be an indication of dependence.

Here the poet meets a group of knights and friends who mourn the death of a Duchess of Carinthia and Tyrol, née Countess of Savoy.

They remember the time when the beloved woman was still alive and describe, among other things, a tournament as it used to take place at her court.

In addition to the linguistic similarity of the tournament descriptions, he also saw evidence of this in the otherwise unattested word walke(n) (meaning "balcony"), which is found in both Minnereden.

The lament for the dead is probably more clumsy stylistically, metrically and in terms of rhyme than that of the 'Monastery of Love', but it cannot be ruled out that both are works by a poet whose skill in writing has increased.

In the Lament for a Noble Duchess, the author calls himself a "junker", as in the Monastery of Love, and is a wandering singer of knightly rank.

[53] Even more than 50 years later, there is no certainty: "The model could have been the constitution that Emperor Ludwig the Bavarian gave to the knightly monastery of Ettal founded by him in 1332, but the poet certainly did not intend a realistic depiction.

[54] Research has also seen this connection: "Ettal offered him [the author] the idea of the chivalric monastery, he worked it out roughly"[55] by, for example, turning the master and the mistress into an abbot and an abbess and a prior and a prioress.

But as soon as one stops taking the text seriously, it proves to be a rare gem of parodic literature: In a reversal of classical material and motifs from heroic epic and love poetry, a hero appears in The Monastery of Love who believes he is doing everything right and stumbles from one blunder to the next - a Don Quixote avant la lettre.