The Motorcycle Diaries (book)

Leaving Buenos Aires, Argentina, in January 1952 on the back of a sputtering single cylinder 1939 Norton 500cc dubbed La Poderosa ("The Mighty One"), they desired to explore the South America they only knew from books.

[1] During the formative odyssey Guevara is transformed by witnessing the social injustices of exploited mine workers, persecuted communists, ostracized lepers, and the tattered descendants of a once-great Inca civilization.

By journey's end, they had travelled for a "symbolic nine months" by motorcycle, steamship, raft, horse, bus, and hitchhiking, covering more than 8,000 kilometres (5,000 miles) across places such as the Andes, the Atacama Desert, and the Amazon River Basin.

[4] Ernesto Guevara spent long periods traveling around Latin America during his studies of medicine, beginning in 1948, at the University of Buenos Aires.

In nine months a man can think a lot of thoughts, from the height of philosophical conjecture to the most abject longing for a bowl of soup – in perfect harmony with the state of his stomach.

And if, at the same time, he's a bit of an adventurer, he could have experiences which might interest other people and his random account would read something like this diary.In January 1952, Guevara's older friend, Alberto Granado, a biochemist, and Guevara, decided to take a year off from their medical studies to embark on a trip they had spoken of making for years: traversing South America on a motorcycle, which has metaphorically been compared to carbureted version of Don Quixote's Rocinante.

In total, the journey took Guevara through Argentina, Chile, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Venezuela, Panama, and to Miami, before returning home to Buenos Aires.

The trip was carried out in the face of some opposition by Guevara's parents, who knew that their son was both a severe asthmatic and a medical student close to completing his studies.

Always curious, looking into everything that came before our eyes, sniffing out each corner but only very faintly – not setting down roots in any land or staying long enough to see the substratum of things; the outer limits would suffice.

Unable to get a boat to Easter Island as they intended, they headed north, where Guevara's political consciousness began to stir as he and Granado moved into mining country.

Apart from whether collectivism, the 'communist vermin', is a danger to decent life, the communism gnawing at his entrails was no more than a natural longing for something better, a protest against persistent hunger transformed into a love for this strange doctrine, whose essence he could never grasp but whose translation, 'bread for the poor', was something he understood and, more importantly, that filled him with hope.

We hauled merchandise, carried sacks, worked as sailors, cops and doctors.In Peru, Guevara was impressed by the old Inca civilization, forced to ride in trucks with Indians and animals after The Mighty One broke down.

After a discussion about the poverty in the region, Guevara referred in his notes to the words of Cuban poet José Marti: "I want to link my destiny to that of the poor of this world".

In May they arrived in Lima, Peru and during this time Guevara met doctor Hugo Pesce, a Peruvian scientist, director of the national leprosy program, and an important local Marxist.

However, Guevara was moved by his time with the lepers, remarking that All the love and caring just consist on coming to them without gloves and medical attire, shaking their hands as any other neighbor and sitting together for a chat about anything or playing football with them.

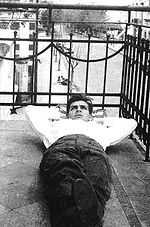

[15]After giving consultations and treating patients for a few weeks, Guevara and Granado left aboard the Mambo-Tango raft (shown) for Leticia, Colombia, via the Amazon River.

In the letter he described the conditions under the right-wing government of Conservative Laureano Gómez as the following: "There is more repression of individual freedom here than in any country we've been to, the police patrol the streets carrying rifles and demand your papers every few minutes".

In circumstances like this, individuals in poor families who can’t pay their way become surrounded by an atmosphere of barely disguised acrimony; they stop being father, mother, sister or brother and become a purely negative factor in the struggle for life and, consequently, a source of bitterness for the healthy members of the community who resent their illness as if it were a personal insult to those who have to support them.Witnessing the widespread endemic poverty, oppression and disenfranchisement throughout Latin America, and influenced by his readings of Marxist literature, Guevara later decided that the only solution for the region's structural inequalities was armed revolution.

His conception of a borderless, united, Hispanic-America, sharing a common mestizo bond, was a theme that would prominently recur during his later activities and transformation from Ernesto the traveler into Che Guevara the iconic revolutionary.

"His political and social awakening has very much to do with this face-to-face contact with poverty, exploitation, illness, and suffering", said Carlos M. Vilas, a history professor at the Universidad Nacional de Lanús in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

[18] Granado later observed that by the end of their journey, "We were just a pair of vagabonds with knapsacks on our backs, the dust of the road covering us, mere shadows of our old aristocratic egos.

This travelogue shows Ernesto the Medical Student developing a sense of Pan-Latin Americanism that fuses the interests of indigenous Andean peasants with traditional adversaries like upper-middle-class Argentine intellectuals (i.e. Guevara).