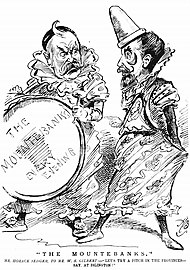

The Mountebanks

The Mountebanks is a comic opera in two acts with music by Alfred Cellier and Ivan Caryll and a libretto by W. S. Gilbert.

The original cast included Geraldine Ulmar, Frank Wyatt, Lionel Brough, Eva Moore and Furneaux Cook.

The idea was clearly important to Gilbert, as he repeatedly urged his famous collaborator, Arthur Sullivan, to set this story, or a similar one, to music.

[5] When that partnership temporarily disbanded, due to a quarrel over finances after the production of The Gondoliers, Gilbert sought another composer who would collaborate on the "magic lozenge" idea that Sullivan had repeatedly rejected.

Dorothy set and held the record for longest-running piece of musical theatre in history until the turn of the century.

[7] He was annoyed when Cellier sailed for Australia in mid-December without having responded to Gilbert's repeated queries about potential conflicts between some plot changes that he had suggested and a recently composed opera of Cellier's with B. C. Stephenson, The Black Mask, including a Spanish setting involving guerillas during the Peninsular War.

[7] Gilbert then completed Act I assuming that there were no conflicts, but finally received a response from Cellier by early January, stating that the change in setting did indeed conflict with his earlier work; Gilbert replied that he was ending the collaboration, and that Horace Sedger, the manager and lessee of London's Lyric Theatre, where the piece was to be produced, agreed with this.

[7] Cellier suffered from tuberculosis for most of his adult life,[8] but during the composition of The Mountebanks he deteriorated rapidly and died, at the age of 47, while the opera was still in rehearsals.

[9] Caryll composed the entr'acte, using the melody from Number 16, and he wrote or modified the orchestration for more than half a dozen of the songs.

[11] After Cellier's illness prevented him from finishing the score, Gilbert modified the libretto around the gaps, and the order of some of the music was changed.

[12] Gilbert engaged his old friends John D'Auban, to choreograph the piece, and Percy Anderson, to design costumes.

"[14] The success of the London production led its producer, Sedger, to establish at least three touring companies,[5] which visited major towns and cities in Britain for a year and a half, from March 1892 to mid-November 1893.

[17] Relations between Gilbert and his new producer had also deteriorated, and the author unsuccessfully sued Sedger for cutting the size of the chorus in the London production without his approval.

[5] Gilbert and Cellier's widow later sold the performing and score rental rights to the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company.

After that, the first known staging was in New York City, in 1955, in a small-scale production at the St. John's Theater, in Greenwich Village, by the Chamber Opera Players, accompanied only by a piano.

[19] A 2015 production was staged in Palo Alto, California by Lyric Theatre, directed by John Hart, using Gordon-Powell's score.

[1][21] One reviewer noted Cellier's "fine lyrical detail and sumptuous orchestration with which he provides a wide variety of musical effects.

… [O]ne is aware of the growing sophistication in Gilbert's choice of words in his lyrics during this mature period of his writing.

"[22] Outside a mountain Inn on a picturesque Sicilian pass, a procession of Dominican monks sings a chorus (in Latin) about the inconveniences of monastic life.

They are a secret society of bandits bent on revenge against the descendants of those who wrongly imprisoned an ancestor's friend five hundred years previously.

Elvino asks them to conduct their revels in a whisper, so as not to disturb the poor old dying alchemist who occupies the second floor of the inn.

Pietro hatches the idea of administering the potion to Bartolo and Nita, who will pretend to be the clock-work Hamlet and Ophelia when the Duke and Duchess arrive.

Pietro brings on Bartolo and Nita to entertain the Duke and Duchess, but he quickly recognises that his audience is only Alfredo and Ultrice.

The Times noted with approval that Gilbert had returned to his favourite device of a magic potion, already seen in The Palace of Truth and The Sorcerer, and found the dialogue "crammed with quips of the true Gilbertian ring."

The reviewer was more cautious about the score, attempting to balance respect for the recently dead Cellier with a clear conclusion that the music was derivative of the composer's earlier works and also of the Savoy operas.

[25] The Pall Mall Gazette thought the libretto so good that it "places Mr Gilbert so very far in advance of any living English librettist."

The paper's critic was more emphatic about the score than his Times colleague, saying, "Mr Cellier's portion of the work is disappointing," adding that the composer never rose in this piece "to within measurable distance of his predecessor.

If we judge the late Alfred Cellier's score by a somewhat high standard it is all Sir Arthur Sullivan's fault.

[citation needed] A later critic, Hesketh Pearson, rated the libretto of The Mountebanks "as good as any but the best Savoy pieces".