The Name of the Rose

[1] It has received many international awards and accolades, such as the Strega Prize in 1981 and Prix Medicis Étranger in 1982, and was ranked 14th on Le Monde's 100 Books of the Century list.

In 1327, Franciscan friar William of Baskerville and his assistant Adso of Melk arrive at a Benedictine abbey in Northern Italy to attend a theological disputation.

The abbey is being used as neutral ground in a dispute between Pope John XXII and the Franciscans over the question of apostolic poverty.

The monks of the abbey have recently been shaken by the suspicious death of one of their brothers, Adelmo of Otranto, and the abbot asks William (a former inquisitor) to investigate the incident.

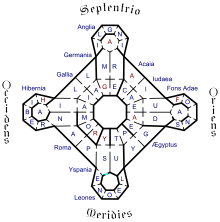

They discover that the library contains a hidden room named the finis Africae after the presumed edge of the world, but they are unable to locate it.

Salvatore is discovered attempting to cast a primitive love spell on the peasant girl, and Bernard arrests them both for witchcraft and heresy.

When William and Adso arrive at Severinus's laboratory, they find him dead, his skull crushed by a heavy armillary sphere.

That night, William and Adso penetrate the library once more and enter the finis Africae by solving Venantius's riddle.

Unbeknownst to him, Jorge had laced its pages with poison, correctly assuming that a reader would have to lick his fingers in order to turn them.

Venantius's body was discovered by Berengar, who, fearing exposure, disposed of it in pig's blood before claiming the book and succumbing to its poison.

The book itself, now back in Jorge's possession, is the lost second half of Aristotle's Poetics, which discusses the virtues of laughter.

Jorge confirms William's deductions and justifies himself by pointing to the fact that the deaths correspond to the seven trumpets described in the Book of Revelation, and therefore must form part of a divine plan.

Years later, Adso, now aged, returns to the ruins of the abbey and salvages any remaining scraps and fragments, eventually creating a lesser library.

Eco was a professor of semiotics, and employed techniques of metanarrative, partial fictionalization, and linguistic ambiguity to create a world enriched by layers of meaning.

Through the motif of this lost and possibly suppressed book which might have aestheticized the farcical, the unheroic and the skeptical, Eco also makes an ironically slanted plea for tolerance and against dogmatic or self-sufficient metaphysical truths – an angle which reaches the surface in the final chapters.

[2] In this regard, the conclusion mimics a novel of ideas, with William representing rationality, investigation, logical deduction, empiricism and also the beauty of the human minds, against Jorge's dogmatism, censoriousness, and pursuit of keeping, no matter the cost, the secrets of the library closed and hidden to the outside world, including the other monks of the abbey.

"[4] After unraveling the central mystery in part through coincidence and error, William of Baskerville concludes in fatigue that there "was no pattern."

[4] In one version of the story, when he had finished writing the novel, Eco hurriedly suggested some ten names for it and asked a few of his friends to choose one.

[citation needed] A further possible inspiration for the title may be a poem by the Mexican poet and mystic Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (1651–1695): Rosa que al prado, encarnada, te ostentas presuntuosa de grana y carmín bañada: campa lozana y gustosa; pero no, que siendo hermosa también serás desdichada.

In addition, a number of other themes drawn from various of Borges's works are used throughout The Name of the Rose: labyrinths, mirrors, sects, and obscure manuscripts and books.

The ending also owes a debt to Borges's short story "Death and the Compass", in which a detective proposes a theory for the behaviour of a murderer.

Eco seems also to have been aware of Rudyard Kipling's short story "The Eye of Allah", which touches on many of the same themes, like optics, manuscript illumination, music, medicine, priestly authority and the Church's attitude to scientific discovery and independent thought, and which also includes a character named John of Burgos.

Eco was also inspired by the 19th century Italian novelist Alessandro Manzoni, citing The Betrothed as an example of the specific type of historical novel he purposed to create, in which some of the characters may be made up, but their motivations and actions remain authentic to the period and render history more comprehensible.

The setting was inspired by monumental Saint Michael's Abbey in Susa Valley, Piedmont and visited by Umberto Eco.

[22] The novel takes place during the Avignon Papacy and in his Prologue, Adso mentions the election of anti-king Frederick of Austria as a rival claimant to Emperor Louis thirteen years before the story begins.

His portrayal of Bernard Gui in particular has been widely criticized by historians as a caricature; Edward Peters has stated that the character is "rather more sinister and notorious ... than he ever was historically", and he and others have argued that the character is actually based on the grotesque portrayals of inquisitors and Catholic prelates more broadly in eighteenth and nineteenth-century Gothic literature, such as Matthew Gregory Lewis's The Monk (1796).

[41] Eco also personally reported some errors and anachronisms present in various editions of the novel until the revision of 2011: Moreover, still present in the Note before the Prologue, in which Eco tries to place the liturgical and canonical hours: If it is assumed, as logical, that Eco referred to the local mean time, the estimate of the beginning of the hour before dawn and the beginning of Vespers (sunset), so those in the final lines ("dawn and sunset around 7.30 and 4.40 in the afternoon"), giving a duration from dawn to noon equal to or less than that from noon to dusk, is the opposite of what happens at the end of November (it is an incorrect application of the equation of time).