The Night Battles

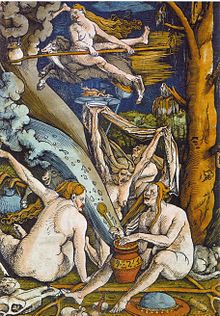

These revolved around their nocturnal visionary journeys, during which they believed that their spirits traveled out of their bodies and into the countryside, where they would do battle with malevolent witches who threatened the local crops.

Considering the benandanti to be "a fertility cult", Ginzburg draws parallels with similar visionary traditions found throughout the Alps and also from the Baltic, such as that of the Livonian werewolf, and also to the widespread folklore surrounding the Wild Hunt.

Despite such criticism, Ginzburg would later return to the theories about a shamanistic substratum for his 1989 book Ecstasies: Deciphering the Witches' Sabbath, and it would also be adopted by historians like Éva Pócs, Gábor Klaniczay, Claude Lecouteux and Emma Wilby.

"[1] Prior to Ginzburg's work, no scholars had investigated the benandanti phenomenon, and those studies which had been made of Friulian folklore – by the likes of G. Marcotti, E. Fabris Bellavitis, V. Ostermann, A. Lazzarini and G. Vidossi – had all used the term "benandante" as synonymous with "witch".

"[4] The Night Battles is divided into four chapters, preceded by a preface written by Ginzburg, in which he discusses the various scholarly approaches that have been taken to studying Early Modern witchcraft, including the rationalist interpretation that emerged in the 18th century and the Witch-cult hypothesis presented by Margaret Murray.

Although Sgabarizza later abandoned his investigations, in 1580 the case was re-opened by the Inquisitor Fra Felice da Montefalco, who interrogated both Gaspurotto and Moduco until they admitted that they had been deceived by the Devil into going on their nocturnal spirit journeys.

[8] He proceeds to examine the trances that the benandanti went into in order to go on their nocturnal spirit journeys, debating whether these visions could have been induced by the use of special psychoactive ointments or by epilepsy, ultimately arguing that neither offer a plausible explanation in light of the historical evidence at hand.

He connects this account with the many other European myths surrounding the Wild Hunt or Furious Horde, noting that in those in central Europe, the name of Diana was supplanted by that of Holda or Perchta.

[13] "A nucleus of fairly consistent and compact beliefs stand out from these dispersed and fragmentary pieces of evidence – beliefs which, in the course of a century, from 1475 to 1585, could be found in a clearly defined area which included Alsace, Württemberg (Heidelberg), Bavaria, the Tyrol; and, on the fringes, Switzerland (the canton of Schwyz)... [I]t seems possible to establish the existence of a thread linking the various pieces of evidence that have been examined thus far: the presence of groups of individuals – generally women – who during the Ember Days fell into swoons and remained unconscious for brief periods of time during which, they affirmed, their souls left their bodies to join the processions of the dead (which were almost always nocturnal) presided over at least in one case by a female divinity (Fraw Selga).

[18] Following on from this, Ginzburg discussed the existence of clerici vagantes who were recorded as travelling around the Swabian countryside in 1544, performing folk magic and claiming that they could conjure the Furious Horde.

[27] In his original Italian preface, Ginzburg noted that historians of Early Modern witchcraft had become "accustomed" to viewing the confessions of accused witches as being "the consequences of torture and of suggestive questioning by the judges".

[28] Ginzburg argues that the benandanti fertility cult was connected to "a larger complex of traditions" that were spread "from Alsace to Hesse and from Bavaria to Switzerland", all of which revolved around "the myth of nocturnal gatherings" presided over by a goddess figure, varyingly known as Perchta, Holda, Abundia, Satia, Herodias, Venus or Diana.

What had been lacking then, and the need persists today if I’m not mistaken, was an all-encompassing explanation of popular witchcraft: and the thesis of the English scholar, purified of its most daring affirmations, seemed plausible where it discerned in the orgies of the sabbat the deformation of an ancient fertility rite."

The definitive rejection of Murray's Witch-Cult theories among academia occurred during the 1970s, when her ideas were attacked by two British historians, Keith Thomas and Norman Cohn, who highlighted her methodological flaws.

[32] At the same time, a variety of scholars across Europe and North America – such as Alan Macfarlane, Erik Midelfort, William Monter, Robert Muchembled, Gerhard Schormann, Bente Alver and Bengt Ankarloo – began to publish in-depth studies of the archival records from the witch trials, leaving no doubt that those tried for witchcraft were not practitioners of a surviving pre-Christian religion.

Hungarian historian Gábor Klaniczay asserted that "Ginzburg reformulated Murray's often fantastic and very inadequately documented thesis about the reality of the witches' Sabbath" and thus the publication of I Benandanti in 1966 "reopened the debate about the possible interconnections between witchcraft beliefs and the survival of pagan fertility cults".

[34] Similarly, Romanian historian of religion Mircea Eliade asserted that while Ginzburg's presentation of the benandanti "does not substantiate Murray's entire thesis", it did represent a "well-documented case of the processus through which a popular and archaic secret cult of fertility is transformed into a merely magical, or even black-magical practice under the pressure of the Inquisition.

[36] Echoing these views, in 1999 English historian Ronald Hutton asserted that Ginzburg's ideas regarding shamanistic fertility cults were actually "pretty much the opposite" of what Murray had posited.

[41] Most scholars in the English-speaking world could not read Italian, meaning that when I Benandanti was first published in 1966, the information which it contained remained out of the grasp of the majority of historians studying Early Modern witchcraft in the United States.

[44] Hutton opined that The Night Battles offered "an important and enduring contribution" to historical enquiry, but that Ginzburg's claim that the benandanti's visionary traditions were a survival from pre-Christian practices was an idea resting on "imperfect material and conceptual foundations.

He thought that this approach was a "striking late application" of "the ritual theory of myth", a discredited anthropological idea associated particularly with Jane Ellen Harrison's 'Cambridge group' and Sir James Frazer.