The Population Bomb

[1][2] From the opening page, it predicted worldwide famines due to overpopulation, as well as other major societal upheavals, and advocated immediate action to limit population growth.

Fears of a "population explosion" existed in the mid-20th century baby boom years, but the book and its authors brought the idea to an even wider audience.

Although the Ehrlichs collaborated on the book, the publisher insisted that a single author be credited, and also asked to change their preferred title: Population, Resources, and Environment.

The Ehrlichs argue that as the existing population was not being fed adequately, and as it was growing rapidly, it was unreasonable to expect sufficient improvements in food production to feed everyone.

"[12] The department should support research into population control, such as better contraceptives, mass sterilizing agents, and prenatal sex discernment (because families often continue to have children until a male is born.

Countries with sufficient programmes in place to limit population growth, and the ability to become self-sufficient in the future would continue to receive food aid.

This is focused primarily on changing public opinion to create pressure on politicians to enact the policies they suggest, which they believed were not politically possible in 1968.

[15] The book sold over two million copies, raised the general awareness of population and environmental issues, and influenced 1960s and 1970s public policy.

[16] In 1948, two widely read books were published that would inspire a "neo-Malthusian" debate on population and the environment: Fairfield Osborn’s Our Plundered Planet and William Vogt’s Road to Survival.

Luten has said that although the book is often seen as a seminal work in the field, The Population Bomb is actually best understood as "climaxing and in a sense terminating the debate of the 1950s and 1960s.”[18] Ehrlich has said that he traced his own Malthusian beliefs to a lecture he heard Vogt give when he was attending university in the early 1950s.

Still other commentators have criticized the Ehrlichs' perceived inability to acknowledge mistakes, evasiveness, and refusal to alter their arguments in the face of contrary evidence.

"[22] In The Population Bomb's opening lines the authors state that nothing can prevent famines in which hundreds of millions of people will die during the 1970s (amended to 1970s and 1980s in later editions), and that there would be "a substantial increase in the world death rate."

[24] The Indian economist and Nobel Memorial Prize winner, Amartya Sen, has argued that nations with democracy and a free press have virtually never suffered from extended famines.

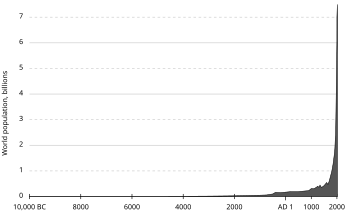

[32] Economist Julian Simon and medical statistician Hans Rosling pointed out that the failed prediction of 70s famines were based exclusively on the assumption that exponential population growth will continue indefinitely and no technological or social progress will be made.

According to environmentalist Stewart Brand, himself a student and friend of Ehrlich, the assumption made by the latter and by authors of The Limits to Growth has been "proven wrong since 1963" when the demographic trends worldwide have visibly changed.

Pierre Desrochers and Christine Hoffbauer remark that "at the time of writing The Population Bomb, Paul and Anne Ehrlich should have been more cautious and revised their tone and rhetoric, in light of the undeniable and already apparent errors and shortcomings of Osborn and Vogt’s analyses.

He quotes a review from Natural History noting that Ehrlich does not try to "convince intellectually by mind dulling statistics," but rather roars "like an Old Testament Prophet.

[39] Desrochers and Hoffbauer go on to conclude that it seems hard to deny that using an alarmist tone and emotional appeal were the main lessons that the present generation of environmentalists learned from Ehrlich's success.

On the political left the book received criticism that it was focusing on "the wrong problem", and that the real issue was one of distribution of resources rather than of overpopulation.

[1] Marxists worried that Paul and Anne Ehrlich's work could be used to justify genocide and imperial control, as well as oppression of minorities and disadvantaged groups or even a return to eugenics.

[40] Eco-socialist Barry Commoner argued that the Ehrlichs were too focused on overpopulation as the source of environmental problems, and that their proposed solutions were politically unacceptable because of the coercion that they implied, and because the cost would fall disproportionately on the poor.

The alternative was overwhelming famines and massive damage to the environment.In a 2004 Grist Magazine interview,[43] Ehrlich acknowledged some specific predictions he had made, in the years around the time The Population Bomb was published, that had not come to pass.

My view has become depressingly mainline!In another retrospective article published in 2009, Ehrlich said, in response to criticism that many of his predictions had not come to pass:[1] the biggest tactical error in The Bomb was the use of scenarios, stories designed to help one think about the future.

But they did deal with future issues that people in 1968 should have been thinking about – famines, plagues, water shortages, armed international interventions by the United States, and nuclear winter (e.g., Ehrlich et al. 1983, Toon et al. 2007)—all events that have occurred or now still threatenIn a 2018 interview with The Guardian, Ehrlich, while still proud of The Population Bomb for starting a worldwide debate on the issues of population, acknowledged weaknesses of the book including not placing enough emphasis on climate change, overconsumption and inequality, and countering accusations of racism.

He advocated for an "unprecedented redistribution of wealth" in order to mitigate the problem of overconsumption of resources by the world's wealthy, but said "the rich who now run the global system — that hold the annual 'world destroyer' meetings in Davos — are unlikely to let it happen.