Art in the Protestant Reformation and Counter-Reformation

Reformed leaders, especially Huldrych Zwingli and John Calvin, actively eliminated imagery from churches within the control of their followers, and regarded the great majority of religious images as idolatrous.

It was just for this reason that reformers favoured a single dramatic coup, and many premature acts in this line sharply increased subsequent hostility between Catholics and Calvinists in communities – for it was generally at the level of the city, town or village that such actions occurred, except in England and Scotland.

But reformers often felt impelled by strong personal convictions, as shown by the case of Frau Göldli, on which Zwingli was asked to advise.

Zwingli's letter advised trying to pay the nuns a larger sum on condition they did not replace the statue, but the eventual outcome is unknown.

[12] By the end of his life, after iconoclastic shows of force became a feature of the early phases of the French Wars of Religion, even Calvin became alarmed and criticised them, realizing that they had become counter-productive.

[13] Subjects prominent in Catholic art other than Jesus and events in the Bible, such as Mary and saints were given much less emphasis or disapproved of in Protestant theology.

As a result, in much of northern Europe, the Church virtually ceased to commission figurative art, placing the dictation of content entirely in the hands of the artists and lay consumers.

[2] The Beeldenstorm, a large and very disorderly wave of Calvinist mob destruction of Catholic images and church fittings that spread through the Low Countries in the summer of 1566 was the largest outbreak of this sort, with drastic political repercussions.

[16] This campaign of Calvinist iconoclasm "provoked reactive riots by Lutheran mobs" in Germany and "antagonized the neighbouring Eastern Orthodox" in the Baltic region.

Frequently Bruegel painted agricultural landscapes, such as Summer from his famous set of the seasons, where he shows peasants harvesting wheat in the country, with a few workers taking a lunch break under a nearby tree.

Italian painting after the 1520s, with the notable exception of the art of Venice, developed into Mannerism, a highly sophisticated style, striving for effect, that concerned many churchmen as lacking appeal for the mass of the population.

Previous Catholic Church councils had rarely felt the need to pronounce on these matters, unlike Orthodox ones which have often ruled on specific types of images.

Statements are often made along the lines of "The decrees of the Council of Trent stipulated that art was to be direct and compelling in its narrative presentation, that it was to provide an accurate presentation of the biblical narrative or saint’s life, rather than adding incidental and imaginary moments, and that it was to encourage piety",[20] but in fact the actual decrees of the council were far less explicit than this, though all of these points were probably in line with their intentions.

The decree confirmed the traditional doctrine that images only represented the person depicted, and that veneration to them was paid to the person themself, not the image, and further instructed that: ...every superstition shall be removed ... all lasciviousness be avoided; in such wise that figures shall not be painted or adorned with a beauty exciting to lust... there be nothing seen that is disorderly, or that is unbecomingly or confusedly arranged, nothing that is profane, nothing indecorous, seeing that holiness becometh the house of God.

Many traditional iconographies considered without adequate scriptural foundation were in effect prohibited, as was any inclusion of classical pagan elements in religious art, and almost all nudity, including that of the infant Jesus.

[25] Likewise, "Lutheran places of worship contain images and sculptures not only of Christ but also of biblical and occasionally of other saints as well as prominent decorated pulpits due to the importance of preaching, stained glass, ornate furniture, magnificent examples of traditional and modern architecture, carved or otherwise embellished altar pieces, and liberal use of candles on the altar and elsewhere.

[26] Sydney Joseph Freedberg, who invented the term Counter-Maniera, cautions against connecting this more austere style in religious painting, which spread from Rome from about 1550, too directly with the decrees of Trent, as it pre-dates these by several years.

[27] Scipione Pulzone's (1550–1598) painting of the Lamentation which was commissioned for the Church of the Gesù in 1593 is a Counter-Maniera work that gives a clear demonstration of what the holy council was striving for in the new style of religious art.

Ten years after the Council of Trent's decree Paolo Veronese was summoned by the Venetian Holy Inquisition to explain why his Last Supper, a huge canvas for the refectory of a monastery, contained, in the words of the Inquisition: "buffoons, drunken Germans, dwarfs and other such scurrilities" as well as extravagant costumes and settings, in what is indeed a fantasy version of a Venetian patrician feast.

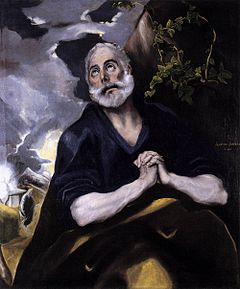

The image typically shows Peter in tears, as a half-length portrait with no other figures, often with hands clasped as at right, and sometimes "the cock" in the background; it was often coupled with a repentant Mary Magdalen, another exemplar from Bellarmine's book.

[33] As the Counter-Reformation grew stronger and the Catholic Church felt less threat from the Protestant Reformation, Rome once again began to assert its universality to other nations around the world.

The religious order of the Jesuits or the Society of Jesus, sent missionaries to the Americas, parts of Africa, India and eastern Asia and used the arts as an effective means of articulating their message of the Catholic Church's dominance over the Christian faith.

The Jesuits' impact was so profound during their missions of the time that today very similar styles of art from the Counter-Reformation period in Catholic Churches are found all over the world.