The Right to Privacy (article)

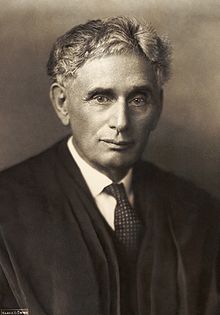

Beginning with the fourth paragraph, Warren and Brandeis explain the desirability and necessity that the common law adapt to recent inventions and business methods—namely, the advent of instantaneous photography and the widespread circulation of newspapers, both of which have contributed to the invasion of an individual's privacy.

Warren and Brandeis take this opportunity to excoriate the practices of journalists of their time, particularly aiming at society gossip pages: The press is overstepping in every direction the obvious bounds of propriety and of decency.

In other words, defamation law, regardless of how widely circulated or unsuited to publicity, requires that the individual suffer a direct effect in his or her interaction with other people.

Second, in the next several paragraphs, the authors examine intellectual property law to determine if its principles and doctrines may sufficiently protect the privacy of the individual.

Warren and Brandeis concluded that "the protection afforded to thoughts, sentiments, and emotions, expressed through the medium of writing or of the arts, so far as it consists in preventing publication, is merely an instance of the enforcement of the more general right of the individual to be let alone."

Warren and Brandeis observed that, although the court in Prince Albert v. Strange asserted that its decision was based on the protection of property, a close examination of the reasoning reveals the existence of other unspecified rights—that is, the right to be let alone.

If this conclusion is correct, then existing law does afford "a principle which may be invoked to protect the privacy of the individual from invasion either by the too enterprising press, the photographer, or the possessor of any other modern device for recording or reproducing scenes or sounds."

Furthermore, Warren and Brandeis suggest the existence of a right to privacy based on the jurisdictional justifications used by the courts to protect material from publication.

In other words, the courts created a legal fiction that contracts implied a provision against publication or that a relationship of trust mandated nondisclosure.

As a closing note, Warren and Brandeis suggest that criminal penalties should be imposed for violations of the right to privacy, but the pair decline to further elaborate on the matter, deferring instead to the authority of the legislature.

[13]Contemporary scholar Neil M. Richards notes that this article and Brandeis' dissent in Olmstead v. United States together "are the foundation of American privacy law".