The Seven Crystal Balls

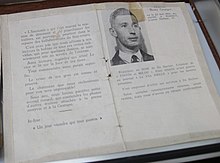

The Seven Crystal Balls (French: Les 7 Boules de cristal) is the thirteenth volume of The Adventures of Tintin, the comics series by Belgian cartoonist Hergé.

The Seven Crystal Balls was a commercial success and was published in book form by Casterman shortly after its conclusion, while the series itself became a defining part of the Franco-Belgian comics tradition.

The next day, Tintin and Haddock learn that members of the Sanders-Hardiman expedition are falling into comas, with fragments of a shattered crystal ball found near each victim.

Under police guard, Professor Tarragon shows his visitors one of the expedition's discoveries from Peru: the mummified body of Inca king Rascar Capac.

Spending the stormy night at Tarragon's house, Tintin, Haddock, and Calculus are each awoken by a dream involving Capac's mummy throwing a crystal ball to the floor.

Tintin visits a hospital where the seven stricken members of the Sanders-Hardiman expedition are housed; he is astonished that at a precise time of day, all awaken and scream about figures attacking them before slipping back into their comas.

[4] Some Belgians were upset that Hergé was willing to work for a newspaper controlled by the occupying Nazi administration,[5] although he was heavily enticed by the size of Le Soir's readership, which reached 600,000.

[6] Faced with the reality of Nazi oversight, Hergé abandoned the overt political themes that had pervaded much of his earlier work, instead adopting a policy of neutrality.

[7] Without the need to satirise political types, entertainment producer and author Harry Thompson observed that "Hergé was now concentrating more on plot and on developing a new style of character comedy.

[8] Following the culmination of his previous Tintin adventure, Red Rackham's Treasure, Hergé had agreed to a proposal that would allow the newspaper to include a detective story revolving around his characters, Thomson and Thompson.

Titled Dupont et Dupond, détectives ("Thomson and Thompson, Detectives"), Hergé provided the illustrations, and the story was authored by Le Soir crime writer Paul Kinnet.

The story was probably inspired by an article authored by Le Soir's science correspondent, Bernard Heuvelmans, and while Hergé did not use this idea at the time, he revived it a decade later as the basis for The Calculus Affair.

[13] The two became close friends and artistic collaborators, as Jacobs aided Hergé in developing various aspects of the plot, such as the idea of the crystal balls and the story's title.

[18] Hergé also included a number of characters who had previously appeared in earlier adventures, among them Professor Cantonneau from The Shooting Star,[19] General Alcazar from The Broken Ear,[20] and Bianca Castafiore from King Ottokar's Sceptre.

[20] The scenery and background of the story was meticulously copied from existing sources; car model types like the Opel Olympia 38 in which Calculus' abductors escaped the police were drawn from real examples,[21] while Hergé closely adhered to the reality of the port and docks at Saint-Nazaire.

[30] This would be the first of four incidents in which Hergé was arrested and freed: by the State Security, the Judiciary Police, the Belgian National Movement, and the Front for Independence, during which he spent one night in jail.

[31] On 8 September the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force issued a proclamation announcing that "any journalist who had helped produce a newspaper during the occupation was for the time being barred from practising his profession".

[33] A newspaper closely associated with the Belgian Resistance, La Patrie, issued a strip titled The Adventures of Tintin in the Land of the Nazis, in which Hergé was lampooned as a collaborator.

[39] Although this period allowed him an escape from the pressure of daily production which had affected most of his working life,[28] he also had family problems to deal with; his brother Paul returned to Brussels from a German prisoner-of-war camp and their mother had become highly delusional and was moved to a psychiatric hospital.

[40] In October 1945, Hergé was approached by Raymond Leblanc, a former member of a conservative Resistance group, the National Royalist Movement (MNR), and his associates André Sinave and Albert Debaty.

[43] Concerned about the judicial investigation into Hergé's wartime affiliations, Leblanc convinced William Ugeux, a leader of the Belgian Resistance who was now in charge of censorship and certificates of good citizenship, to look into the comic creator's file.

He closed the case on 22 December, declaring that "in regard to the particularly inoffensive character of the drawings published by Remi, bringing him before a war tribunal would be inappropriate and risky".

"[51] He considered the post-war trials of collaborators a great injustice inflicted upon many innocent people,[52] and never forgave Belgian society for the way that he had been treated, although he hid this from his public persona.

[27] After the story had finished serialisation, the publishing company Casterman divided it into two volumes, Les Sept Boules de Cristal and Le Temple du Soleil, which they released in 1948 and 1949 respectively.

[65] Fellow biographer Pierre Assouline believed that The Seven Crystal Balls achieved "a more complete integration of narrative and illustrations" than previous adventures,[66] and that from that point on, his books "begin to form a coherent body of work, an oeuvre".

[67] Harry Thompson stated that the "overriding theme" of The Seven Crystal Balls was "fear of the unknown", adding that while it did blend humour with menace, it remained "Hergé's most frightening book".

[68] Michael Farr described both The Seven Crystal Balls and Prisoners of the Sun as "classic middle-period Tintin", commenting on their "surprisingly well-balanced narrative" and noting that they exhibited scant evidence of Hergé's turbulent personal life.

[62] He felt that The Seven Crystal Balls encapsulated the "air of doom" which pervaded the mood of Europe at the time to an even greater extent than Hergé had done in his earlier work, The Shooting Star.

[69] They noted that The Seven Crystal Balls is "bathed in the surreal atmosphere that Hergé knew how to create so well", with Tintin confronting "a dark and oppressive force" that was "worthy of a Hammer film".

[75] In his psychoanalytical study of the Adventures of Tintin, the academic Jean-Marie Apostolidès believed that The Seven Crystal Balls-Prisoners of the Sun arc reflects a confrontation between civilisations, and between the sacred and the secular.