The Spirit of the Age

[14] His brother John was also responsible for helping him connect with other like-minded souls,[15] leading him to the centre of London intellectual culture, where he met others who, years later, along with Wordsworth, Coleridge, and Godwin, would be brought to life in this book, particularly Charles Lamb[16] and, some time afterward, Leigh Hunt.

After the French Revolution had given fresh urgency to the question of the rights of man, in 1793, in response to other books written in reaction to the upheaval, and building on ideas developed by 18th-century European philosophers,[56] Godwin published An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice.

But Hazlitt was impressed by its strong literary qualities, and, to a lesser extent, those of St. Leon, exclaiming: "It is not merely that these novels are very well for a philosopher to have produced—they are admirable and complete in themselves, and would not lead you to suppose that the author, who is so entirely at home in human character and dramatic situation, had ever dabbled in logic or metaphysics.

[81] He notes Coleridge's profound and exhaustive exploration of more recent philosophy—including that of Hartley, Priestley, Berkeley, Leibniz, and Malebranche—and theologians such as Bishop Butler, John Huss, Socinus, Duns Scotus, Thomas Aquinas, Jeremy Taylor, and Swedenborg.

He who has seen a mouldering tower by the side of a chrystal lake, hid by the mist, but glittering in the wave below, may conceive the dim, gleaming, uncertain intelligence of his eye; he who has marked the evening clouds uprolled (a world of vapours), has seen the picture of his mind, unearthly, unsubstantial, with gorgeous tints and ever-varying forms ...[90] The Reverend Edward Irving (1792–1834) was a Scottish Presbyterian minister who, beginning in 1822, created a sensation in London with his fiery sermons denouncing the manners, practices, and beliefs of the time.

Having been involved in politics over a long life, Tooke could captivate his audience with his anecdotes, especially in his later years: He knew all the cabals and jealousies and heart-burnings in the beginning of the late reign [of King George III], the changes of administration and the springs of secret influence, the characters of the leading men, Wilkes, Barrè, Dunning, Chatham, Burke, the Marquis of Rockingham, North, Shelburne, Fox, Pitt, and all the vacillating events of the American war:—these formed a curious back-ground to the more prominent figures that occupied the present time ...[117] Hazlitt felt that Tooke would be longest remembered, however, for his ideas about English grammar.

"[119] That Murray's book should have been the grammar to have "proceeded to [its] thirtieth edition" and find a place in all the schools instead of "Horne Tooke's genuine anatomy of the English tongue" makes it seem, exclaims Hazlitt, "as if there was a patent for absurdity in the natural bias of the human mind, and that folly should be stereotyped!".

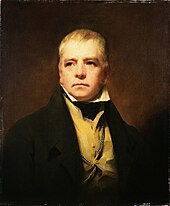

[139] Hazlitt sarcastically observes that Scott appeared to want to obliterate all of the achievements of centuries of civilised reform and revive the days when "witches and heretics" were burned "at slow fires", and men could be "strung up like acorns on trees without judge or jury".

Surveying the range of Southey's voluminous writings, constituting a virtual library,[179] Hazlitt finds worth noting "the spirit, the scope, the splendid imagery, the hurried and startled interest"[179] of his long narrative poems, with their exotic subject matter.

Even at the time Hazlitt was writing this essay, "The vulgar do not read [Wordsworth's poems], the learned, who see all things through books, do not understand them, the great despise, the fashionable may ridicule them: but the author has created himself an interest in the heart of the retired and lonely student of nature, which can never die.

[212] However, later persuaded by Burke himself to renounce his earlier views about the Revolution, Mackintosh, in his 1799 lectures at Lincoln's Inn (published as A Discourse on the Study of the Law of Nature and Nations), attended by Hazlitt, reversed his position, subjecting reformers, particularly Godwin, to severe criticism, and dealing a blow to the liberal cause.

Looking back at the elder man's change of political sentiments, Hazlitt observed that the lecturer struck a harsh note if he felt it were a triumph to have exulted in the end of all hope for the "future improvement" of the human race; rather it should have been a matter for "lamentation".

As he analyses the characteristics of Mackintosh as a public speaker, a conversationalist, and a scholarly writer, Hazlitt traces the progress of his life, noting his interactions with Edmund Burke over the French Revolution, his tenure as chief judge in India, and his final career as Member of Parliament.

"[220] But there is a fatal flaw in all this impressive intellectual "juggling"[221] (which, Tom Paulin notes, alludes to Hazlitt's earlier contrast between the deft but mechanical "Indian jugglers" and representatives of true genius):[222] his performances were "philosophical centos", the thoughts of others simply stitched together.

Hazlitt, who heard him speak in Parliament, observes that, just as his previous appointment as a judge in India was unsuited to a man who worked out his thought in terms of "school-exercises", Mackintosh's mind did not fit well the defender of political causes, which needed more passionate engagement.

... Sir James, in detailing the inexhaustible stores of his memory and reading, in unfolding the wide range of his theory and practice, in laying down the rules and the exceptions, in insisting upon the advantages and the objections with equal explicitness, would be sure to let something drop that a dexterous and watchful adversary would easily pick up and turn against him...."[224] Mackintosh, like Coleridge, shines as one of the great conversationalists in an age of "talkers, not of doers".

[229] As an open attack on schemes of Utopian reform advocated by Godwin and Condorcet, Malthus's book soon drew support from conservative politicians, who used it as an excuse to attempt to dismantle the Poor Laws, setting a trend that continued for centuries.

In Hazlitt's day, at least one major political faction claimed that direct public assistance to alleviate poverty was ineffective, maintaining that businesses pursuing profit would automatically result in the best social conditions possible, allowing the inevitability of some attrition of the poor by disease and starvation.

"[239] For, the greater the comfort introduced into the lives of the masses by the advance of "virtue, knowledge, and civilization", the more inexorable will be the action of the "principle of population", "the sooner will [civilisation] be overthrown again, and the more inevitable and fatal will be the catastrophe .... famine, distress, havoc, and dismay ... hatred, violence, war, and bloodshed will be the infallible consequence ...."[240] "Nothing", Hazlitt asserts, "could be more illogical";[239] for if, as Godwin and other reformers maintained, man is capable of being "enlightened", and "the general good is to obtain the highest mastery of individual interests, and reason of gross appetite and passions", then by that very fact it is absurd to suppose that men "will show themselves utterly blind to the consequences of their actions, utterly indifferent to their own well-being and that of all succeeding generations, whose fate is placed in their hands.

[260] Hazlitt then elaborates on the methods of Gifford's Quarterly Review, in which he and his "friends systematically explode every principle of liberty, laugh patriotism and public spirit to scorn, resent every pretence to integrity as a piece of singularity or insolence, and strike at the root of all free inquiry or discussion, by running down every writer as a vile scribbler and a bad member of society, who is not a hireling and a slave.

[271] With a distinct Whig political bias, but also notable for encouraging fair, open discourse,[272] and with a mission of educating the upper and increasingly literate middle classes, the Edinburgh Review was the most prestigious and influential periodical of its kind in Europe for more than two decades at the time Hazlitt wrote this sketch.

"[278] Alarmed, Hazlitt asserts sarcastically, at the danger that this free spirit posed to the "Monarchy [and the] Hierarchy", the founders of the Quarterly set up a periodical that would "present [itself as] one foul blotch of servility, intolerance, falsehood, spite, and ill manners.

[297] If the Irish orator riots in a studied neglect of his subject and a natural confusion of ideas, playing with words, ranging them into all sorts of combinations, because in the unlettered void or chaos of his mind there is no obstacle to their coalescing into any shapes they please, it must be confessed that the eloquence of the Scotch is encumbered with an excess of knowledge, that it cannot get on for a crowd of difficulties, that it struggles under a load of topics, that it is so environed in the forms of logic and rhetoric as to be equally precluded from originality or absurdity, from beauty or deformity ...

Eldon, as Lord Chancellor, later continued to help enforce the government's severe reaction to the civil unrest in the wake of the French Revolution and during the Napoleonic Wars, and was a notoriously persistent blocker of legal reforms as well as of the speedy resolution of lawsuits over which he presided.

The Lord Chancellor, as an example of a good-natured man, "would not hurt a fly ... has a fine oiliness in his disposition .... does not enter into the quarrels or enmities of others; bears their calamities with patience ... [and] listens to the din and clang of war, the earthquake and the hurricane of the political and moral world with the temper and the spirit of a philosopher ...".

"[315] And in this (Hazlitt here continues his psychological explanation) he follows a common human tendency: "Where remote and speculative objects do not excite a predominant interest and passion, gross and immediate ones are sure to carry the day, even in ingenuous and well-disposed minds.

[355] Cobbett's sympathy for the working classes,[356] disadvantaged by an economy undergoing wrenching upheavals,[357] endeared him to them and greatly influenced popular opinion,[358] as his unrelenting criticism of corruption and waste in the political establishment provoked government persecution, leading to imposition of fines,[359] imprisonment,[360] and self-imposed exile in the United States.

In such works as the Twopenny Post-bag and, to a lesser degree, The Fudge Family in Paris, Moore's "light, agreeable, polished style pierces through the body of the court ... weighs the vanity of fashion in tremulous scales, mimics the grimace of affectation and folly, shows up the littleness of the great, and spears a phalanx of statesmen with its glittering point as with a diamond brooch.

Irving, he notes, has absorbed the refined style of the older writers and writes well: "Mr. Irvine's [sic] language is with great taste and felicity modeled on that of Addison, Goldsmith, Sterne, or Mackenzie"; but what he sees might have been seen with their eyes, and are such as are scarcely to be found in modern England.

[532] With its combination of critical analysis and personal sketches of notable figures captured "in the moment", Hazlitt in The Spirit of the Age laid the groundwork for much of modern journalism[533] and to an extent even created a new literary form, the "portrait essay" (although elements of it had been anticipated by Samuel Johnson and others).