Thomas Moore

Today Moore is best remembered for his Irish Melodies (typically "The Minstrel Boy" and "The Last Rose of Summer"), his chivalric romance Lalla Rookh and, less generously, for the role he is thought to have played in the loss of the memoirs of his friend Lord Byron.

With their encouragement, in 1797, Moore wrote an appeal to his fellow students to resist the proposal, then being canvassed by the English-appointed Dublin Castle administration, to secure Ireland by incorporating the kingdom in a union with Great Britain.

[9] Later, in a biography of the United Irish leader Lord Edward Fitzgerald (1831),[10] he made clear his sympathies, not hiding his regret that the French expedition under General Hoche failed in December 1796 to effect a landing.

The impecunious student was assisted by friends in the expatriate Irish community in London, including Barbara, widow of Arthur Chichester, 1st Marquess of Donegall, the landlord and borough-owner of Belfast.

His introduction to the future prince regent and King, George IV was a high point in Moore's ingratiation with aristocratic and literary circles in London, a success due in great degree to his talents as a singer and songwriter.

In the same year he collaborated briefly as a librettist with Michael Kelly in the comic opera, The Gypsy Prince, staged at the Theatre Royal, Haymarket,[13] In 1801, Moore hazarded a collection of his own verse: Poetical Works of the Late Thomas Little Esq..

Although as late as 1925 still recalled as "the poet laureate" of the island, Moore found life on Bermuda sufficiently dull that after six months he appointed a deputy and left for an extended tour of North America.

Repelled by the provincialism of the average American, Moore consorted with exiled European aristocrats, come to recover their fortunes, and with oligarchic Federalists from whom he received what he later conceded was a "twisted and tainted" view of the new republic.

Francis Jeffrey denounced the volume in the Edinburgh Review (July 1806), calling Moore "the most licentious of modern versifiers", a poet whose aim is "to impose corruption upon his readers, by concealing it under the mask of refinement.

In 1821, several emigres, prominent among them Myles Byrne (a veteran of Vinegar Hill and of Napoleon's Irish Legion) refused to attend a St Patrick's day dinner Moore had organised in Paris because of the presiding presence of Wellesley Pole Long, a nephew of the Duke of Wellington.

But with the antics of the Prince Regent, and in particular, his highly public efforts to disgrace and divorce Princess Caroline, proving a lightning rod for popular discontent, they were finding new unity and purpose.

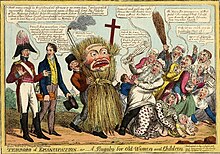

In what were the "verbal equivalents of the political cartoons of the day",[6] Tom Crib's Memorial to Congress (1818) and Fables for the Holy Alliance (1823), Moore lampoons Castlereagh's deference to the reactionary interests of Britain's continental allies.

[32] For openly casting the same dispersions against the former Chief Secretary—that he bloodied his hands in 1798 and deliberately deceived Catholics at the time of the Union—in 1811 the London-based Irish publisher, and former United Irishman, Peter Finnerty was sentenced to eighteen months for libel.

It was only after this catastrophe, which as Prime Minister Moore's Whig friend, Lord Russell, failed in any practical measure to allay,[37] that British governments began to assume responsibility for agrarian conditions.

Moore lived to see the exceptional papal discretion thus confirmed reshaping the Irish hierarchy culminating in 1850 with the appointment of the Rector of the Sacred Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith in Rome, Paul Cullen, as Primate Archbishop of Armagh.

Oppressed by the charge that Catholics are "a race of obstinate and obsolete religionists […] unfit for freedom", and freed from "the point of honour" that would have prevented him from abandoning his church in the face of continuing sanctions, he sets out to explore the tenets of the "true" religion.

[45][46] Predictably, the resolve the young man draws from his theological studies is to remain true to the faith of his forefathers (not to exchange "the golden armour of the old Catholic Saints" for "heretical brass").

Moore's purpose, he was later to write, was to put "upon record" the "disgust" he felt at "the arrogance with which most Protestant parsons assume […] credit for being the only true Christians, and the insolence with which […] they denounce all Catholics as idolators and Antichrist".

[48] Had his young man found "among the Orthodox of the first [Christian] ages" one "particle" of their rejection of the supposed "corruptions" of the Roman church – justification not by faith alone but also by good works, transubstantiation, and veneration of saints, relics and images — he would have been persuaded.

The Second Travels of an Irish Gentleman in Search of Religion (1833)[49] was a vindication of the reformed faith by an author described as "not the editor of Captain Rock's Memoirs" — the Spanish exile and Protestant convert Joseph Blanco White.

Without the prospect of obtaining power – which in Ireland is "lodged in a branch of the English government" (the Dublin Castle executive) – there is little point in the members of parliament, no matter how personally disinterested, collaborating for any public purpose.

[53] It is against this, the truncated state of politics in Ireland, that Moore sees Lord Edward Fitzgerald, a "Protestant reformer" who wished for "a democratic House of Commons and the Emancipation of his Catholic countrymen", driven toward the republican separatism of the United Irishmen.

[57] He believed it would give "an opening and impulse to the revolutionary feeling now abroad" [England, Moore suggested, had been "in the stream of a revolution for some years"][58] and that the "temporary satisfaction" it might produce would be but as the calm before a storm: "a downward reform (as Dryden says) rolls on fast".

In conversation with the Whig grandee Lord Lansdowne, he argued that while the consequences might be "disagreeable" for many of their friends, "We have now come to that point which all highly civilised countries reach when wealth and all the advantages that attend it are so unequally distributed that the whole is in an unnatural position: and nothing short of a general routing up can remedy the evil.

Following a request by the publishers James and William Power, he wrote lyrics to a series of Irish tunes in the manner of Haydn's settings of British folksongs, with Sir John Andrew Stevenson as arranger of the music.

[17] The "ultra-Tory" The Anti-Jacobin Review ("Monthly Political and Literary Censor")[68] discerned in Moore's Melodies something more than innocuous drawing-room ballads: "several of them were composed in a very disordered state of society, if not in open rebellion.

[73] In A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, as he passes "the droll statue of the national poet of Ireland" in College Street, James Joyce's biographic protagonist, Stephen Dedalus, remarks on the figure's "servile head".

Despite Joyce's occasional expressions of disdain for the bard, critic Emer Nolan suggests that the writer responded to the "element of utopian longing as well as the sentimental nostalgia" in Moore's music.

Greek-Rumanian conspirators against the Sultan, Russian Decembrists and, above all, Polish intellectuals recognised in the Gothic elements of the Melodies, Lalla Rookh (“a dramatization of Irish patriotism in an Eastern parable”)[78] and Captain Rock (all of which found translators) "a cloak of culture and fraternity".

Oft, in the stilly night, Ere slumber's chain has bound me, Fond memory brings the light Of other days around me; The smiles, the tears, Of boyhood's years, The words of love then spoken; The eyes that shone, Now dimm'd and gone, The cheerful hearts now broken!...