The Tragical History of Guy Earl of Warwick

[4] Helen Cooper of Cambridge University considers the subject matter, stagecraft, and topical references to point to a composition date just after Christopher Marlowe's plays became influential,[5] and that the text of Guy Earl of Warwick reflects Marlowe's "mighty line" and phrasing, so that the play very likely dates to the early 1590s.

[8] John Peachman, in contrast, cautions that there is no definitive date for Guy Earl of Warwick[9] and proposes that it may have been written in the aftermath of the "Isle of Dogs" affair of 1597.

[10] Based on changes in style within the play, Peachman suggests that Guy Earl of Warwick may be a collaborative work and that the comic scenes revolving around the character Philip Sparrow may, in fact, have been written by Ben Jonson in response to criticism Jonson received from Shakespeare over the Isle of Dogs affair.

[9][a] The epilogue of Guy Earl of Warwick provides one clue as to authorship: the narrator says, "...For he's but young that writes of this Old Time," and promises better works in the future if the audience will be patient with him.

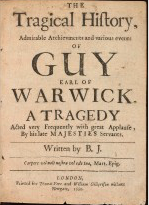

Guy Earl of Warwick was published by Thomas Vere and William Gilbertson in 1661, and the title page states that the play was written by "B.J."

[11] A lost play, "the life and death of Guy of Warwicke" (sic) by Thomas Dekker and John Day was entered in the Stationers' Register in 1620.

[14] Guy Earl of Warwick's popular, romantic subject matter, along with stylistic similarities to works by Thomas Dekker (particularly Old Fortunatas)[15] lead Moore to believe that the Guy Earl of Warwick published in 1661 is based on the Dekker/Day play recorded in 1620, which could itself be a revision of a play composed c.

[20] From the simplicity of the sets and the small number of properties required to perform the play, Helen Moore deduced that the surviving text might have been derived from a touring company's prompt book.

Guy tells Phillis that in his selfish pursuit of her love he has neglected God, and that he has determined to travel to Jerusalem and fight the Mohammedans.

The battle won, Guy vows to see the Holy Sepulcher, lay down his arms, and lead a life of peace and repentance.

[24] The reference to a Dun Cow adventure seems to derive from a lost 1592 ballad, "A pleasant songe of the valiant actes of Guy of Warwicke.

[26] In her 2006 article about Guy Earl of Warwick, Helen Cooper of Cambridge University wrote: It has been almost entirely overlooked in modern scholarship, perhaps because its topic does not fit with either the classicising or the early modern approaches to the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, perhaps because its date of publication lets it fall into the gap between study of the Renaissance and the Restoration.

In addition, it does not advance traditional humanist notions of quality or coherence: it has no concern with such niceties as character development, and its second act seems to have wandered in from another play.

[28] In her introduction to the 2007 Malone Society edition of Guy Earl of Warwick, Helen Moore of Oxford University says that the primary impetus for printing the play in 1661 was simple revival of pre-Restoration drama, but she also notes that Guy Earl of Warwick may have been "particularly congenial" subject matter in the 1660s, when plays often addressed themes of usurpation, restoration, virtue, and recovery.

[33] John Berryman, writing in 1960 and building on Harbage's work, argues that because four parts of the attack against Shakespeare found in Groats-Worth - low birth, thievishness, arrogance, and a pun on Shakespeare's name - are also found in Guy Earl of Warwick, it seems likely that the writer of Guy Earl of Warwick was a purposeful imitator of Greene.

[34][d] Helen Cooper agrees that the description of Sparrow "...is too pointed...to be a random formulation...," but she asserts that the character does not necessarily constitute an attack on Shakespeare.

[37] Cooper speculates that if Shakespeare could be connected to the production of Guy Earl of Warwick in some way, it would influence future scholarship regarding plays as diverse as King Lear and A Midsummer Night's Dream.

[39]In 2009, John Peachman explored close textual connections between Guy Earl of Warwick and Mucedorus, the best selling play of the 17th century,[40] but of author unknown.

Given the rarity of the parallels, that they are all concentrated within a single scene of Mucedorus, and that in each case the lines involve the clown characters of the plays, Peachman concluded that it was very unlikely that the similarities were coincidental.

[43] Peachman concludes that Guy Earl of Warwick's borrowings from Mucedorus may have been intended to emphasize to an audience "...that Sparrow was a hit at Shakespeare.

"[43] In her introduction to the Malone Society edition, Helen Moore downplays the likelihood that Sparrow is meant to represent Shakespeare.

[45] To the contrary, Sparrow's dialogue is in "essentially the literary southern dialect that was frequently used for comic purposes in early modern drama.

[47] The title page to the 1661 published version of Guy Earl of Warwick states that it had been "Acted very Frequently with great Applause By his late Majesties Servants."