The Way to Divine Knowledge

Law himself lived in the Age of Enlightenment centering on reason in which there were many controversies between Catholics and Protestants, Deists, Socinians, Arians etc.

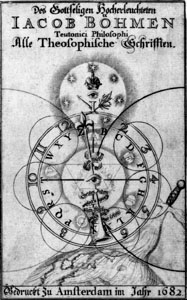

[6] According to some, William Law had been considering to publish a new edition of the works of Jakob Boehme which would help readers to make the "right use of them".

[10] Humanus is the "learned unbeliever" and represents the deists (also referred to as the "infidels")[11] [12] who had been raised as Christians, but who had doubts as to the Trinity, as well as with orthodox teachings and with the supernatural interpretations of miracles.

Academicus represents the intellectuals and their close study of Latin, Greek or even Hebrew literary texts which enabled them to discuss fine points of historical and theological differences.

In the Atonement passages in The Way to Divine Knowledge Law again asserted, as he had done in his previous books especially from 1737 and onwards, that the redemption of Christ was an example of "God's mercy to all mankind".

[13] However, Law realized that this concept of "the nature and necessity of regeneration" would be totally rejected by those who believed in "guilt, righteous anger, retributive punishment, compensatory justice and sacrificial death.

[17][18] Theophilus argues that "the fall of man into the life and state of this world is the whole ground of his redemption, and that a real birth of Christ in the soul is the whole nature of it".

[19] That is the reason why one should look up "in faith and hope to God as our Father and to Heaven as our native country" and why we are only "strangers and pilgrims upon earth".

[22]Theophilus was very pleased with the progress Humanus had made, especially with his resolution not to enter into debate about the Gospel doctrines with his [old Brethren] till they were ready for it and wanted to be saved and if that time should never come Humanus must consider them as disciples of Epicurus: For every man that cleaves to this world, that is in love with it, and its earthly enjoyments, is a disciple of Epicurus, and sticks in the same mire of atheism as he did whether he be a modern Deist, a Popish or Protestant Christian, an Arian or an orthodox teacher.

He thought that Theophilus would publish a new edition of Boehme's works removing "most of his strange and unintelligible words and give us notes and explications of such as you do not alter".

Then Rusticus stepped in, representing Law's view of skipping over several possibly bewildering passages in Jakob Boehme's books.

Rusticus admonished Academicus by telling him about his neighbour John the Shepherd and his wife Betty: Oh this impatient scholar!

In winter evenings when he comes out of the field, his own eyes being bad, the old woman his wife puts on her spectacles and reads about an hour to him, sometimes out of the Scriptures, and sometimes out of Jacob Behmen for he has two or three of his books.

For John had rather the feeling of the gospel in his heart even if he did not understand it all than all those difficult explanations of the head (of learned men).

[25] Rusticus was clearly annoyed with the impatience of Academicus for to understand the "truths of Jacob Behmen" one must stand where he stood, where he began and seek only the heart of God.

[26] This in turn annoyed Academicus who said that renouncing all his learning and reason if he was to understand Jacob Behmen was something which he was not resolved to purchase at so high a price.

I esteem the liberal arts and sciences as the noblest of human things, I desire no man to dislike or renounce his skill in ancient or modern languages, his knowledge of medals, pictures, paintings, history, geography or chronology.

.... Now whether this awakened new man breathes forth his faith and hope towards this divine life in Hebrew, Greek or English sounds or in no one of them, can be of no significance.

[27]Theophilus had explained to Academicus that the redemption is possible for everyone who has their inward man "kindled into love, hope and faith in God" and who is capable of the highest divine illumination, while "learned students full of art and science can live and die without the least true knowledge of God and Christ": This redemption belongs only to one sort of people and yet is common to all.

There is no difference between learned and unlearned, Jew of Greek, male or female, Scythian or barbarian, bond or free.

[29] Academicus had been reading "cart-loads of lexicons, critics and commentators upon the Hebrew Bible", books on Church History, all the councils and canons made in every age, Calvin and Cranmer, Chillingworth and Locke, the discourses of Mr. Boyle and Lady Moyer's lectures, the Clementine constitutions, dr. Clarke and mr. Whiston might be useful, all the Arian and Socinian writers, all the histories of the rise and progress of heresies and of the lives and characters of the heretics, etc., a list of some of the books in Law's own library.

[33] They did this all in vain because: No one has so deeply and from so true a ground laid open the exceeding vanity of such labour and utter impossibility of success in it from any art or skill in the use of fire.

[35] Unfortunately, so Theophilus continued, we call everything knowledge "that the reason, wit or humour of man prompts him to discourse about", whether it is fiction, conjecture, report, history, criticism, rhetoric or oratory.

[36] This was according to Theophilus the great delusion which had overspread the Christian world and all countries and libraries were the proof of it: It is all this power and dominion of reason in religious matters that Jacob Behmen so justly calls the antichrist ... for it leads ... [to] a confused multitude of contrary notions, inventions and opinions.

.... Reason ruling in divine things turns the living mysteries of God into lifeless ideas and vain opinions [because] it sets up a worldly kingdom of strife, hatred, envy, division and persecution in defence of them.

[45] Stephen Hobhouse (1881–1961) stated that for many readers of Law's works the concept of the seven properties of nature had been bewildering and therefore his advice was to skip these passages.

[51]Theophilus ended the third dialogue by returning to the cause of all the controversies of the Church, beginning with St. Austugine and Pelagius who in the fifth century A.D. wrangled about the freedom of the human will, followed by the horrible wars as the result from different interpretations of the Gospel between Catholics and Protestants.

The truth is only then found when it is known to be of no sect, but as free and universal as the goodness of God and as common to all names and nations, as the air and light of this world.

The Way to Divine Knowledge rather than helping to understand the philosophy of Jakob Boehme almost reads like a defence by Law (as Theophilus) against the attacks upon his mystically inclined works, which some critics, represented by Humanus and Academicus, found unorthodox.

Of all of Law's works the most widely appreciated by his contemporaries and those of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries were the ones written before 1737, especially A Practical Treatise upon Christian Perfection (1726) and A Serious Call to a Devout and Holy Life (1729).