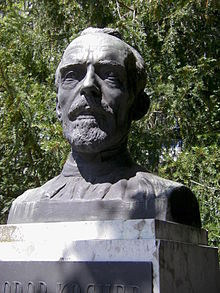

Emil Theodor Kocher

[5] During high school, Theodor was interested in many subjects and was specifically drawn to art and classical philology but finally decided to become a doctor.

[6] He started his studies after obtaining the Swiss Matura in 1858 at the University of Bern where Anton Biermer and Hermann Askan Demme were teaching, two professors that impressed him most.

He obtained his doctorate in Bern in 1865[7][8] (March 1865)[5] or 1866[2] [note 1] with his dissertation about Behandlung der croupösen Pneumonie mit Veratrum-Präparaten (literal English translation: The treatment of croupous pneumonia with Veratrum preparations.)

[5] It is not clear how Kocher financed his trip but according to Bonjour (1981) he received money from an unknown female Suisse romande philanthropist who also supported his friend Marc Dufour and was probably a member of the Moravian Church.

Since there was no position available, in April 1867 Kocher moved on to London where he first met Jonathan Hutchinson and then worked for Henry Thompson and John Erichsen.

Furthermore, he was interested in the work of Isaac Baker Brown and Thomas Spencer Wells, who also invited Kocher to go to the opera with his family.

[5] Once returned to Bern, Kocher prepared for his habilitation and on 12 October 1867, he wrote a petition to the ministry of education to award him the venia docendi (Latin: to instruct) which was granted to him.

Under this public pressure, the Bernese government (Regierungsrat) chose Kocher as the successor of Lücke as Ordinary Professor of Surgery and Director of the University Surgical Clinic at the Inselspital on 16 March 1872, despite a different proposal by the faculty.

The house became a place for friends, colleagues and guests to gather and many patients from Kocher's clinic were invited to dine at the Villette.

This was an uncommon trait that not many colleagues and co-workers shared and until his death, Kocher attributed all his successes and failures to God.

[5] The call for an ordinary professorship at the University of Bern at the age of 30 was the first big career step for Theodor Kocher.

In the 45 years he served as professor at the university, he oversaw the re-building of the famous Bernese Inselspital, published 249 scholarly articles and books, trained numerous medical doctors and treated thousands of patients.

and an 1875 manuscript Ueber die Sprengwirkung der modernen Kriegsgewehrgeschosse (English: Over the explosive effect of modern war rifle bullets.)

He noticed that the old building did not suffice the modern standards and was too small – half of the patients seeking medical attention had to be turned away.

He wrote down his observations in a lengthy report for the Bernese government, giving instructions even for architectonic details.

[5] Kocher had recognized the importance of aseptic techniques early on, introducing them to his peers at a time when this was considered revolutionary.

[9] Thyroid surgery, which was mostly performed as treatment of goitre with a complete thyroidectomy when possible, was considered a risky procedure when Kocher started his work.

[12] Through application of modern surgical methods, such as antiseptic wound treatment and minimizing blood loss, and the famous slow and precise style of Kocher, he managed to reduce the mortality of this operation from an already low 18% (compared to contemporary standards) to less than 0.5% by 1912.

Kocher, neat and precise, operating in a relatively bloodless manner, scrupulously removed the entire thyroid gland doing little damage outside its capsule.

Billroth, operating more rapidly and, as I recall, with less regard for the tissues and less concern for hemorrhage, might easily have removed the parathyroids or at least have interfered with their blood supply, and have left fragments of the thyroid.Kocher and others later discovered that the complete removal of the thyroid could lead to cretinism (termed cachexia strumipriva by Kocher) caused by a deficiency of thyroid hormones.

[15] Kocher then tried to contact 77 of his 102 former patients and found signs of a physical and mental decay in those cases where he had removed the thyroid gland completely.

[16] Ironically, it was his precise surgery that allowed Kocher to remove the thyroid gland almost completely and led to the severe side effects of cretinism.

Kocher came to the conclusion that a complete removal of the thyroid (as it was common to perform at the time because the function of the thyroid was not yet clear) was not advisable, a finding that he made public on 4 April 1883 in a lecture to the German Society of Surgery and also published in 1883 under the title Ueber Kropfexstirpation und ihre Folgen (English: About Thyroidectomies and their consequences).

[13] Kocher published works on a number of subjects other than the thyroid gland, including hemostasis, antiseptic treatments, surgical infectious diseases, on gunshot wounds, acute osteomyelitis, the theory of strangulated hernia, and abdominal surgery.

[11] One of his main works, Chirurgische Operationslehre (Text-Book of Operative Surgery [19]), was published through six editions and translated into many languages.

[5] This association with Russia has also led the Russian Geographical Society to name a volcano after him (in the area of Ujun-Choldongi [5] in Manchuria[11] ).

[5] Other notable students of his include Hayazo Ito (1865–1929) and S. Berezowsky which also spread his techniques in their respective home-countries (Japan and Russia).