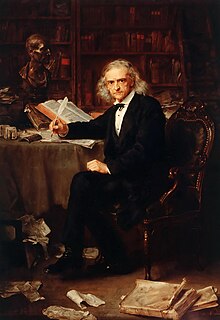

Theodor Mommsen

He received the 1902 Nobel Prize in Literature for his historical writings, including The History of Rome, after having been nominated by 18 members of the Prussian Academy of Sciences.

Mommsen was born to German parents in Garding in the Duchy of Schleswig in 1817, then ruled by the king of Denmark, and grew up in Bad Oldesloe in Holstein, where his father was a Lutheran minister.

Thanks to a royal Danish grant, Mommsen was able to visit France and Italy to study preserved classical Roman inscriptions.

During the revolution of 1848 he worked as a war correspondent in then-Danish Rendsburg, supporting the German annexation of Schleswig-Holstein and a constitutional reform.

Mommsen received high recognition for his academic achievements: foreign membership of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1859,[1] the Prussian medal Pour le Mérite in 1868, honorary citizenship of Rome, elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society in 1870,[2] and the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1902 for his main work Römische Geschichte (Roman History).

[11] Mommsen had sixteen children with his wife Marie (daughter of the publisher and editor Karl Reimer of Leipzig).

While he was secretary of the Historical-Philological Class at the Berlin Academy (1874–1895), Mommsen organised countless scientific projects, mostly editions of original sources.

The basic principle of the edition (contrary to previous collections) was the method of autopsy, according to which all copies (i.e., modern transcriptions) of inscriptions were to be checked and compared to the original.

Furthermore, he played an important role in the publication of the Monumenta Germaniae Historica, the edition of the texts of the Church Fathers, the limes romanus (Roman frontiers) research and countless other projects.

[12] In 1879, his colleague Heinrich von Treitschke began a political campaign against Jews (the so-called Berliner Antisemitismusstreit).

Mommsen strongly opposed antisemitism and wrote a harsh pamphlet in which he denounced von Treitschke's views.

Mommsen viewed a solution to antisemitism in voluntary cultural assimilation, suggesting that the Jews could follow the example of the people of Schleswig-Holstein, Hanover and other German states, which gave up some of their special customs when integrating into Prussia.

[17] There is a Gymnasium (academic high school) named for Mommsen in his hometown of Bad Oldesloe, Schleswig-Holstein, Germany.

Mark Twain was an honoured guest, seated at the head table with some twenty 'particularly eminent professors'; and it was from this vantage point that he witnessed the following incident..."[18] In Twain's own words: When apparently the last eminent guest had long ago taken his place, again those three bugle-blasts rang out, and once more the swords leaped from their scabbards.

Still, indolent eyes were turned toward the distant entrance, and we saw the silken gleam and the lifted sword of a guard of honor plowing through the remote crowds.