Walls of Constantinople

According to the late Byzantine Patria of Constantinople, ancient Byzantium was enclosed by a small wall that began on the northern edge of the acropolis, extended west to the Tower of Eugenios, then went south and west towards the Strategion and the Baths of Achilles, continued south to the area known in Byzantine times as Chalkoprateia, and then turned, in the area of the Hagia Sophia, in a loop towards the northeast, crossed the regions known as Topoi and Arcadianae and reached the sea at the later quarter of Mangana.

According to the account of Cassius Dio, the city held out against Severan forces for three years, until 196, with its inhabitants resorting even to throwing bronze statues at the besiegers when they ran out of other projectiles.

[4] Severus punished the city harshly: the strong walls were demolished, and the town was deprived of its civic status, being reduced to a mere village dependent on Heraclea Perinthus.

[5] However, appreciating the city's strategic importance, Severus eventually rebuilt it and endowed it with many monuments, including a Hippodrome and the Baths of Zeuxippus, as well as a new set of walls, located some 300–400 m to the west of the old ones.

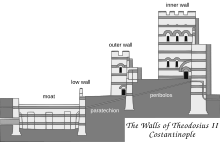

[33] Theodosius II ordered the praetorian prefect Constantine to supervise the repairs, made all the more urgent as the city was threatened by the presence of Attila the Hun in the Balkans.

[12][35] After the Latin conquest of 1204, the walls fell increasingly into disrepair, and the revived post-1261 Byzantine state lacked the resources to maintain them, except in times of direct threat.

Furthermore, while until the Komnenian period, the reconstructions largely remained true to the original model, later modifications ignored the windows and embrasures on the upper story and focused on the tower terrace as the sole fighting platform.

According to Dethier's theory, the former were given names and were open to civilian traffic, leading across the moat on bridges, and the latter were known by numbers, were restricted to military use and led only to the outer sections of the walls.

[66] The debate has been carried over to a now-lost Latin inscription in metal letters that stood above the doors and commemorated their gilding in celebration of the defeat of an unnamed usurper:[67] Haec loca Theudosius decorat post fata tyranni.aurea saecla gerit qui portam construit auro.

(English translation) Theodosius adorned these places after the downfall of the tyrant.He brought a golden age who built the gate from gold.While the legend has not been reported by any known Byzantine author, an investigation of the surviving holes wherein the metal letters were riveted verified its accuracy.

[64] According to descriptions of Pierre Gilles and English travelers from the 17th century, these reliefs were arranged in two tiers, and featured mythological scenes, including the Labours of Hercules.

[100] From Byzantine texts it appears that the correct form is Gate of Rhesios (Πόρτα Ῥησίου), named according to the 10th-century Suda lexicon after an ancient general of Greek Byzantium.

[115] According to the historian Doukas, on the morning of 29 May 1453, the small postern called Kerkoporta was left open by accident, allowing the first fifty or so Ottoman troops to enter the city.

[133] It is an architecturally excellent fortification, consisting of a series of arches closed on their outer face, built with masonry larger than usual and thicker than the Theodosian Walls, measuring some 5 m at the top.

Its Turkish name comes from the sharp bend of the road in front of it to pass around a tomb which is supposed to belong to Hazret Hafiz, a companion of Muhammad who died there during the first Arab siege of the city.

[139] A walled-up postern after the second tower is commonly identified with the Gyrolimne Gate (πύλη τῆς Γυρολίμνης, pylē tēs Gyrolimnēs), named after the Argyra Limnē, the "Silver Lake", which stood at the head of the Golden Horn.

The two walls form a fortified enclosure, called the Brachionion or Brachiolion ("bracelet") of Blachernae (βραχιόνιον/βραχιόλιον τῶν Βλαχερνῶν) by the Byzantines, and known after the Ottoman capture of the city in Greek as the Pentapyrgion (Πενταπύργιον, "Five Towers"), in allusion to the Yedikule (Gk.

[145] Schneider identified it in part with the Pteron (Πτερόν, "wing"), built at the time of Theodosius II to cover the northern flank of the Blachernae (hence its alternate designation as proteichisma, "outwork") from the Anemas Prison to the Golden Horn.

[150] The seaward walls (Greek: τείχη παράλια, teichē paralia) enclosed the city on the sides of the Sea of Marmara (Propontis) and the gulf of the Golden Horn (χρυσοῦν κέρας).

[154] This two-phase construction remains the general consensus, but Cyril Mango doubts the existence of any seaward fortifications during Late Antiquity, as they are not specifically mentioned as extant by contemporary sources until much later, around the year 700.

Enemy access to the walls facing the Golden Horn was prevented by the presence of a heavy chain or boom, installed by Emperor Leo III (r. 717–741), supported by floating barrels and stretching across the mouth of the inlet.

As these repairs coincided with the capture of Crete by the Saracens, no expense was spared: As Constantine Manasses wrote, "the gold coins of the realm were spent as freely as worthless pebbles".

Other repairs are recorded in 1434, again to defend against the Genoese, and again in the years leading up to the final siege and fall of the city to the Ottomans, partly with funds provided by the Despot of Serbia, George Brankovic.

[168] The northern shore of the city was always its more cosmopolitan part: a major focal point of commerce, it also contained the quarters allocated to foreigners living in the imperial capital.

In Buondelmonti's map, it is labelled Porta Piscaria, on account of the fishmarket that used to be held there, a name that has been preserved in its modern Turkish appellation, Balıkpazarı Kapısı, "Gate of the Fish-market".

Sergius and Bacchus, and the first of the harbours of the city's southern shore, that of the Sophiae, named after the wife of Emperor Justin II (r. 565–578) and known originally as the Port of Julian.

[208] Further to the west, where the shoreline turns sharply south, stood the Gate of Psamathia (Πόρτα τοῦ Ψαμαθᾶ/Ψαμαθέως, Porta tou Psamatha/Psamatheos), modern Samatya Kapısı, leading to the suburb of the same name.

In times of need, such as the earthquake of 447 or the raids by the Avars in the early 7th century, the general population, organized in the guilds and the hippodrome factions, would be conscripted and armed, or additional troops would be brought in from the provincial armies.

The settlement declined and disappeared after the 7th century, leaving only the great tower (the kastellion tou Galatou) in modern Karaköy, that guarded the chain extending across the mouth of the Golden Horn.

With cannons mounted on its main towers, the fort gave the Ottomans complete control of the passage of ships through Bosphorus, a role evoked by its original name, Boğazkesen ("cutter of the strait").