Theory of the Portuguese discovery of Australia

Although Scotsman Alexander Dalrymple wrote on this topic in 1786,[13] it was Richard Henry Major, Keeper of Maps at the British Museum, who in 1859 first made significant efforts to prove the Portuguese visited Australia before the Dutch.

[15]: 358 [16]: 42–43 Writing in an academic journal in 1861, Major announced the discovery of a map by Manuel Godinho de Eredia,[17] claiming it proved a Portuguese visit to North Western Australia, possibly dated to 1601.

[21] Fluent in Portuguese and Spanish, Collingridge was inspired by the publicity surrounding the arrival in Australia of copies of several Dieppe maps, which had been purchased by libraries in Melbourne, Adelaide and Sydney.

[31] In 1987, the Australian Minister for Science, Barry Jones, launching the Second Mahogany Ship Symposium in Warrnambool, said "I read Kenneth McIntyre's important book ... as soon as it appeared in 1977.

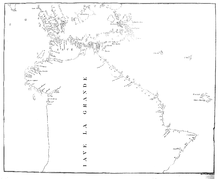

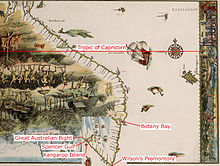

[36] Later writers on the same topic take the same approach of concentrating primarily on "Jave la Grande" as it appears in the Dieppe maps, including Fitzgerald, McKiggan and most recently, Peter Trickett.

[16]: 5 McIntyre attributed discrepancies between the Jave la Grande coastline and Australia's to the difficulties of accurately recording positions without a reliable method of determining longitude, and the techniques used to convert maps to different projections.

[39][40] Both Lawrence Fitzgerald and Peter Trickett argue Jave la Grande is based on Portuguese sea charts, now lost, which the mapmakers of Dieppe misaligned.

[45] McIntyre nominated Cristóvão de Mendonça as the commander of a voyage to Australia c. 1521–1524, one he argued had to be kept secret because of the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas, which divided the undiscovered world into two-halves for Portugal and Spain.

Barros and other Portuguese sources do not mention a discovery of land that could be Australia, but McIntyre conjectured this was because original documents were lost in the 1755 Lisbon earthquake,[46] or the official policy of silence.

[47] Most proponents of the theory of Portuguese discovery of Australia have supported McIntyre's hypothesis that it was Mendonça who sailed down the eastern Australian coast and provided charts which found their way onto the Dieppe maps, to be included as "Jave la Grande" in the 1540, 1550s and 1560s.

[51] In the 1970s and 1980s, linguist Carl Georg von Brandenstein, approaching the theory from another perspective, claimed that 60 words used by Aboriginal people of the Australian north-west had Portuguese origins.

[53]Von Brandenstein also claimed the Portuguese had established a "secret colony ... and cut a road as far as the present day town of Broome"[54] and that "stone housing in the east Kimberley could not have been made without outside influence".

[63][64] Kenneth McIntyre suggested that although Cornelis de Jode was Dutch, the title page of Speculum Orbis Terrae may provide evidence of early Portuguese knowledge of Australia.

However, as macropods (including the dusky pademelon, agile wallaby, and black dorcopsis) are found in New Guinea and the Bismarck Archipelago, this may have no relevance to a possible Portuguese discovery of Australia.

[68] Parkin transcribed the relevant Journal entry as "...anchored in 4 fathom about a mile from the shore and then made a signal for the boats to come onboard, after which I went myself and buoy’d the channel which I found very narrow and the harbour much smaller than I had been told but very convenient for our purpose.

[71] According to McIntyre, the remains of one of Cristóvão de Mendonça's caravels was discovered in 1836 by a group of shipwrecked whalers while they were walking along the sand dunes to the nearest settlement, Port Fairy.

[75] In 1847, at Limeburners Point, near Geelong, Victoria, Charles La Trobe, a keen amateur geologist, was examining shells and other marine deposits revealed by excavations associated with lime production in the area.

[77][80] In January 2012, a swivel gun found two years before at Dundee Beach near Darwin was widely reported by web news sources and the Australian press to be of Portuguese origin.

[89] McIntyre hypothesized the crew of a Portuguese caravel may have built a stone blockhouse and defensive wall while wintering on a voyage of discovery down Australia's east coast.

[90] Pearson identified the Bittangabee Bay ruins as having been built as a store house by the Imlay brothers, early European inhabitants, who had whaling and pastoral interests in the Eden area.

[92] Trickett accepts Pearson's work, but hypothesizes that the Imlays may have started their building on top of a ruined Portuguese structure, thus explaining the surrounding rocks and partly dressed stones.

Matthew Flinders cast a sceptical eye over the "Great Java" of the Dieppe maps in A Voyage to Terra Australis, published in 1814, and concluded: "it should appear to have been partly formed from vague information, collected, probably, by the early Portuguese navigators, from the eastern nations; and that conjecture has done the rest.

Advocates of the Portuguese discovery theory endeavour to explain away this embarrassing lack of direct supporting evidence as being due to two factors: the Portuguese official secrets policy, which must have been applied with a degree of efficiency that is hard to credit, and the 1755 Lisbon earthquake which, they claim, must have destroyed all the relevant archival material.He dismisses the claim that Cristóvão de Mendonça sailed down the east coast of Australia as sheer speculation, based on voyages about which no details have survived.

Richardson argues that McIntyre's practice of re-drawing sections of maps in his book was misleading because, in an effort to clarify, he actually omitted crucial features and names that did not support the Portuguese discovery theory.

Emeritus Professor Victor Prescott has claimed Richardson "brilliantly demolished the argument that Java la Grande show(s) the east coast of Australia.

[101] In 1984, criticism of The Secret Discovery of Australia also came from master mariner Captain A. Ariel, who argued McIntyre had made serious errors in his explanation and measurement of "erration" in longitude.

Brunelle noted that, in design and decorative style the Dieppe maps represented a blending of the latest knowledge circulating in Europe with older visions of world geography deriving from Ptolemy and mediaeval cartographers and explorers such as Marco Polo.

[107] In an article published in 2022, based on a presentation made to an international workshop at the Biblioteca Nacional, Lisbon, King said that there was no evidence in Portuguese records and charts of the early 16th century that their navigators discovered Australia.

[108] The Jave la Grande and Terre de Lucac of the Dieppe maps represented Marco Polo's Java Major and Locach, displaced by the map-makers who misconstrued the information on Southeast Asia and America brought back by Portuguese and Spanish navigators.

[109] In a subsequent article, he argues that the Dieppe mapmakers identified Java Major (Jave la Grande) or, in the case of Guillaume Brouscon Locach (Terre de lucac), with Oronce Fine's Regio Patalis.