Gavin Menzies

Rowan Gavin Paton Menzies (14 August 1937 – 12 April 2020)[1][2][3] was a British submarine lieutenant-commander who authored books claiming that the Chinese sailed to America before Columbus.

Menzies' second book, 1434: The Year a Magnificent Chinese Fleet Sailed to Italy and Ignited the Renaissance, extended his discovery hypothesis to the European continent.

The ensuing enquiry found Menzies and one of his subordinates responsible for a combination of factors that led to the accident, including the absence of the coxswain (who usually takes the helm in port) who had been replaced by a less experienced crew member, and technical issues with the boat's telegraph.

[13] Menzies retired the next year, and campaigned unsuccessfully as an independent candidate in Wolverhampton South West during the 1970 United Kingdom general election, where—standing against Enoch Powell—he called for unrestricted immigration to Great Britain, drawing 0.2% of the vote.

[22] Menzies trained as a barrister, but in 1996 he was declared a vexatious litigant by HM Courts Service which prohibited him from taking legal action in England and Wales without prior judicial permission.

[15] Bonomi contacted the firm Midas Public Relations to persuade a major newspaper to run a promotional article for Menzies's book.

Menzies paid £1,200 to reserve a lecture hall at the Royal Geographical Society in order to unveil his claims; that was enough to convince The Daily Telegraph to write an article about his speculations.

[15] The book is written informally, as a series of vignettes of Menzies' travels around the globe examining what he claims is evidence for his "1421 hypothesis", interspersed with speculation regarding the achievements of Admiral Zheng He's fleet.

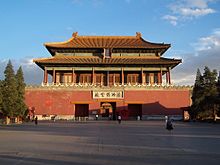

[15] He claims that from 1421 to 1423, during the Ming dynasty of China under the Yongle Emperor, the fleets of Admiral Zheng He, commanded by the captains Zhou Wen, Zhou Man, Yang Qing, and Hong Bao, discovered Australia, New Zealand, the Americas, Antarctica, and the Northeast Passage; circumnavigated Greenland, tried to reach the North and South Poles, and circumnavigated the world before Ferdinand Magellan.

[28] Menzies bases his main theory on original interpretations and extrapolations of academic studies of minority population DNA, archaeological finds, and ancient maps.

Menzies claims that knowledge of Zheng He's discoveries was subsequently lost because the mandarin bureaucrats of the Ming imperial court feared that the costs of further voyages would ruin the Chinese economy.

[15] In 2004, historian Robert Finlay severely criticized Menzies in the Journal of World History for his "reckless manner of dealing with evidence" that led him to propose hypotheses "without a shred of proof".

The fundamental assumption of the book—that the Yongle Emperor dispatched the Ming fleets because he had a "grand plan", a vision of charting the world and creating a maritime empire spanning the oceans—is simply asserted by Menzies without a shred of proof ...

"[32] A group of scholars and navigators—Su Ming Yang of the United States, Jin Guo-Ping and Malhão Pereira of Portugal, Philip Rivers of Malaysia, Geoff Wade of Singapore—questioned Menzies' methods and findings in a joint message:[28] His book 1421: The Year China Discovered the World, is a work of sheer fiction presented as revisionist history.

[33] Academics have emphatically rejected all of this "evidence" as worthless and have criticized what American history professor Ronald H. Fritze calls the "almost cult-like" manner in which Menzies drummed up support for his hypothesis.

He claims that a letter written in 1474 by Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli and found amongst the private papers of Columbus indicates that an earlier Chinese ambassador had direct correspondence with Pope Eugene IV in Rome.

Menzies then claims that materials from the Chinese Book of Agriculture, the Nong Shu, published in 1313 by the Yuan-dynasty scholar-official Wang Zhen (fl.

1290–1333), were copied by European scholars and provided direct inspiration for the illustrations of mechanical devices which are attributed to the Italian Renaissance polymaths Taccola (1382–1453) and Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519).

He arrived at the conclusion that the solution method does not depend on this text but on the earlier Sunzi Suanjing as does the treatment of a similar problem by Fibonacci which predates the Mathematical Treatise in Nine Sections.