Thermal power plant of Vouvry

Initially planned on the territory of the commune of Aigle in the canton of Vaud, it benefited from its proximity to the Collombey refinery [fr], enabling it to produce electricity at preferential rates.

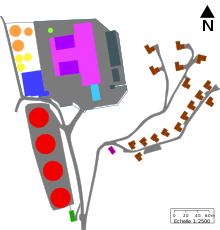

It consists of two plateaus and a slope and includes a main building housing the machine room, a 120-meter exhaust chimney, four cooling towers, a cable car station, and 17 villas, which Chavalon employees previously inhabited.

The plant is connected to the Collombey refinery by a pipeline that primarily traverses the Stockalper Canal [fr], which was utilized to provide makeup water.

[5] The plant buildings are distributed on a slope and two platforms are constructed from biogenic sedimentary rocks and evaporites based on limestone and, on occasion, marl.

[9] In 1959, the company Énergie de l'Ouest-Suisse [fr] (EOS) sought a solution to enhance its electricity production during winter months.

[10] The presence of the Collombey refinery [fr] also facilitated the supply of a potential plant at favorable prices, thereby further motivating its construction.

In February 1961, a construction permit application was filed for a 150 MW plant with a 120-meter chimney at the site called "Les Îles."

[9] Following several appeals from the population and the commune of Ollon, the Council of State of Vaud imposed a minimum chimney height of 300 meters.

This prompted a reaction from the Federal Office of Aviation, which declared in January 1962 that such a tall chimney would be "extraordinarily dangerous" for air navigation and decided to limit its height to 180 meters.

To address the chimney issue, a "fumoduc" was proposed, which would vent the smoke to the Pro de Taila at an altitude of 1,270 meters.

[13] In 1962, the "Porte-du-Scex thermal power plant" company was established, with shareholders including EOS (40%), CFF (15%), Aluminium Suisse (10%), Lonza (10%), Raffineries du Rhône (5%), and Romande Énergie [fr] (5%).

[15] Jean Lugeon, director of the Swiss Meteorological Institute, conducted environmental measurements and concluded that the risk of pollution should not exceed the tolerated time limit.

The intensive use of metal frames and prefabricated parts allowed for the rapid construction of the main building, which was completed in November.

During this period, the production units were rarely shut down, with maintenance performed during the year-end holidays, Easter, and the three to four summer months when they were not in operation.

The units could operate for up to 6,000 hours per year, consuming nearly 400,000 tonnes of heavy fuel oil to generate 1.8 terawatt-hours (TWh) of electricity.

[25] Following the second oil crisis in 1979, the plant's operating costs increased significantly, resulting in 14 million Swiss francs annual losses.

[27] With the staff already laid off, the stock was quickly burned in September 1999 as a precautionary measure,[28] and the plant was officially closed that same month.

[26] Chavalon, the sole oil-fired thermal power plant in Switzerland, employed a workforce that had undergone training provided by Électricité de France (EDF).

The municipality of Vouvry proposed the creation of an energy museum, while EOS initially considered selling portions of the plant to Turkey.

[30] In 2001, the cantonal police stored 35 million Swiss francs worth of seized hemp from Bernard Rappaz in the plant's buildings.

[33] Finally, Chavalon was used as a set for television shows or photo shoots, and its chimney also served as a launch pad for base jumpers.

[30] In parallel with the site's closure, a project has been planned for the construction of a new natural gas combined cycle power plant at Chavalon.

The project, which was subject to a public inquiry in 2007, two years after the Kyoto Protocol came into effect, was deemed "outdated and obsolete" by Marie-Thérèse Sangra, the secretary of WWF for the canton of Valais.

[34] In 2017, EOS and Romande Energie officially announced the project abandonment, stating that the low electricity prices, coupled with the increased costs of CO2 emission compensation, do not ensure the plant's profitability.

Véronique Diab-Vuadens, the president of Vouvry, has stated that the municipality is not interested in pursuing a real estate project at Chavalon.

These sheets, with a thickness ranging from 0.7 to 1 millimeter, exhibited varying profiles depending on the location, including sinusoidal, triangular, and trapezoidal designs.

[44] The blue coloration of select portions of the building was deliberately chosen to contrast with the surrounding natural environment and to accentuate the plant's silhouette against the sky.

The remainder of the pipeline is exposed, with the ascent parallel to the wastewater and makeup water pipes pumped from the Stockalper canal.

The rotor was constructed from a single-piece steel body encased in a bare wire winding, held in place by insulating wedges.

[57] The connection between the alternator and the transformers is established using an aluminum busbar set with a surface area of 11,000 mm², which allowed for a maximum electrical current of 7,800 amperes per phase.