Thief-taker

[4] A major cause was immigration: an impressive number of different cultural groups migrated to the big city in search of fortune and social mobility, contributing to saturate jobs availability and making cohabitation a difficult matter.

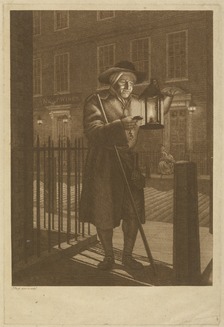

[6] The English judicial system was not very developed in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, as it was based on the Statute of Winchester of 1285, which created a basic organisation for keeping the peace prescribing the contribution of all citizens for: patrolling the streets at night in turns, hurrying to the “hue and cry”, serving as a parish constable for a period of time, and being armed with suitable objects for intervention in case of necessity.

[7] The seventeenth century saw a peculiar phase of political and religious instability: the Glorious Revolution brought William III to reign over England, and the rise of violence in the streets of the capital because of the removal of armed soldiers from service;[2] the government feared conspiracy and felt the urgent need to protect its currency from coiners and clippers;[8] on the other side, a period of poor harvests contributed to deepen people's bad conditions and the issues of public security that poverty originates.

Stealing from shops that exposed their luxury good in their windows was a great temptation to women in particular,[2] who desired to have the latest fashion or imitate the higher social class style.

[10] Furthermore, the freedom of travelling safely was connected to the importance of commercial trades, hence, attacking people on the main roads was a threat to the economic system and already a capital offence.

[15] In the 1690s the criminal activity became so critical that it urged the government to take alternative measures: a series of rewards were introduced by statute to stimulate the prosecution and conviction of felons.

[2] England became involved in the War of the Spanish Succession in 1702, which lasted until 1713, and brought a number of armed ex-soldiers to wander along London streets, who played a part in the rise of violent crime.

[18] The Gordon Riots of 1780, occasioned by the Catholic relief bill of 1778, were of the last manifestations of extreme violence in the streets of London: they caused a great deal of property damages, and their suppression resulted in the killing of many demonstrators by military forces.

[25] At the end of the seventeenth century population in London was incredibly growing and the city borders expanding thanks to the favorable economic situation that attracted a great number of immigrants escaping from poor life conditions.

[34] At the beginning of the eighteenth century part of the original speeches pronounced in trials by prisoners, prosecutors, witnesses and judges started to be printed for the cases thought to be more entertaining for the public; the length was increased, the content reorganised and a space for advertisements created to compete with newspapers in captivating new readers.

[40] The national government started to be more concerned with crime in the 1690s, leading them to draw upon thief-takers to a greater degree,[40] and to introduce permanent rewards, which were meant to encourage citizens to participate more actively in bringing serious criminals to the justice.

[43][44] Prosecuted felons who managed to save their lives found in collaborating with constables and magistrates a suitable business for them, and a safer option than continuing to risk death penalty for committing serious offences.

[45] In addition to this, thief-takers exploited the demand for arranging the return of stolen goods for a fee advertised in newspapers by the victims of theft,[49] who preferred to have their belongings back than to engage in the costly and uncertain prosecution of their attackers.

When dealing with receivers became more dangerous due to more severe punishments for those suspected of compounding a felony, thieves realised that it was less risky and of bigger profit to return what they took unlawfully.

[59] This kind of trade was highly implemented by the development of the press: newspapers gave the possibility to victims and mediation figures to advertise their rewards and services, so that they became acquainted with each other.

Since negotiating with clients was dangerous as well, because in the case of being perceived as a receiver or to be compounding they could have been accused of felony, Jonathan Wild proved to be prudent in not actually receiving the stolen goods: he only took note on a book of the details of the stolen goods from the victim and left messages to discover where they were, managing to deceive victims into raising the reward to secure the return; or advertised the “loss” on newspapers on behalf of the thieves, and then arranged the exchange.

The dark side was that the supposed protectors had the information and power to blackmail felons to extort money, or to prosecute them for the reward, which they actually did to sustain their own credibility to the authority.

[70] Wild in turn replied anonymously rejecting the accusations and revealing particulars of Hitchen's own dubious past as a receiver and as a thief-taker, thus beginning a pamphlet war.

[72] Corruption, extortion of money and the practice of convicting innocents for profit, or popular gentlemen highwaymen such as the famous Jack Sheppard, turned public opinion against thief-takers.

[72] Wild as well suffered the rage of the Londoners on his way to the place of execution: he was fiercely pelted with stones and repeatedly insulted by the mob, who rushed furiously to Newgate Prison and followed him while transported with an open cart to the gallows.

[49] After the execution of Jonathan Wild, some defendants also begun to claim that they had been induced into committing a felony, thus exploiting the increasing unpopularity of thief-takers' activities in order to discredit the charge.

After the execution of Wild, the Thief-Taker General and corrupt criminal, a void in law enforcement emerged, and public officers nearly repented his death: the number of apprehensions, prosecutions and hangings had decreased significantly, as well as the readiness for the retrieval of the stolen goods.

[49] In 1751 the novelist Henry Fielding wrote a pamphlet entitled Enquiry into the Causes of the late Increase of Robbers, in which he tries to restore the good image of thief-takers, showing how valuable they were for law enforcement and how dangerous for their life it was to secure criminals to the justice: the ill behaviour of a few did not have to erase the laudable services they performed for the community.

[80] Henry and his half-brother John also established a primitive form of organised police force: they hired thief-takers and former constables to go from their magistrate's office in Bow Street and investigate, catch criminals or recover stolen goods.

[82] At the beginning the public was not very willing to this new organisation of law enforcement because the ill practices of thief-takers were not forgotten yet, and it meant also moving a step closer to the establishment of a professional form of policing as in France.

[83] The Bow Street Runners reached quickly the public awareness and approval thanks to the success in defeating a notorious gang of robbers in 1753,[81] and to the massive advertisements published by John Fielding in the newspapers.

Despite complaints about his belligerent methods, he managed to maintain his position because he alleged that he was able to reduce the increased wave of crime generated by the end of the War of the Spanish Succession.

However, under the influence of the moralistic campaign of the Societies for the Reformation of Manners, he was tried in 1727 for sodomy, which was a felony, but found guilty only of assault with sodomitical intent and sentenced to pay a fine, be exposed in the pillory, and be imprisoned for six months.

He was also a receiver of stolen goods into the trade of returning them to the victim to gain the reward, organised thefts, and blackmailed the thieves whom he dealt with in order to make more profit.

[67] John Gibbons owned an official position for the government and took advantage of his role to become a corrupt thief-taker: he pretended to pursue coiners and clippers, but he actually protected them from being prosecuted in exchange for money.