Thirlmere

That on the introduction of any provincial water bill into Parliament, attention should be drawn to the practicability of making the measure applicable to as extensive a district as possible, and not merely to the particular town.

Any major new works should aim to secure adequate supplies for the next thirty or fifty years; these could only be found in the mountains and lakes of northern Lancashire, Westmorland or Cumberland.

[28] The aqueduct, however, was objected to by owners of land through which it would pass: under normal procedure, they would be the only objectors with sufficient locus standi to be heard against the private bill necessary to authorise the scheme.

[29] "If every person who has visited the Lake District, in a true nature-loving spirit would be ready, when the right time comes, to sign an indignant protest against the scheme, surely there might be some hope..." that Parliament would reject the Bill, urged one correspondent, who went on to urge legal protection for natural beauty, along the lines of that proposed for ancient monuments by Sir John Lubbock or for the Yellowstone area in the United States.

Aesthetic opposition to the scheme was aggravated by the suggestion that Manchester Corporation would improve on nature[32] and varied in tone and thoughtfulness: the Carlisle Patriot thought Manchester welcome to take all the water it needed, provided only that it must not "destroy or deface those natural features which constitute the glory of the Lake District" and advised against any attempt to mitigate the offence by tree-planting; Thirlmere had "..a character of its own which makes the suggested artificiality intolerable.

But, taken as a whole, I perceive that Manchester can produce no good art, and no good literature; it is falling off even in the quality of its cotton; it has reversed, and vilified in loud lies, every essential principle of political economy; it is cowardly in war, predatory in peace...[36] and thought it would be more just if instead of Manchester Corporation being allowed to "steal and sell for a profit the water of Thirlmere and clouds of Hevellyn" it should be drowned in Thirlmere.

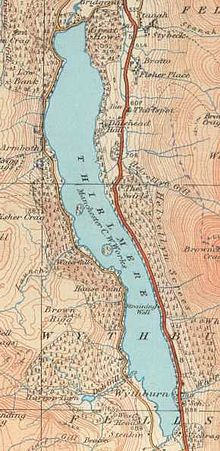

In addition, a section of the existing Keswick-Ambleside turnpike north of Wythburn was to be diverted to run at a higher level, and a new carriage road was to be built on the western side of Thirlmere.

The scheme would destroy the distinctive charm of Thirlmere which was 'entirely free from modern erections out of harmony with the surroundings'; raising the level would destroy the many small bays that gave the west shore its character, the 'picturesque windings' of the existing road on the east side were to be replaced by a dead level road, at the northern end, 'one of the sweetest glens in Cumberland' was to be the site of an enormous embankment.

[41] "Few persons, whose taste is not utterly uneducated, are likely to share the confidence of the water committee in their power to enhance the loveliness of such a scene, or will think that the boldest devices of engineering skill will be other than a miserable substitute for the natural beauties they displace.

[i] Manchester could easily get more (and of superior quality) from wells tapping the New Red Sandstone aquifer; if they were still unsatisfied there were vast untouched collecting grounds in the moorlands of Lancashire.

There was also a more general point; the Thirlmere scheme, if approved, would set a precedent for municipalities to buy up whole valleys in the Lake District, leaving them at the mercy of "bodies of men, skilful and diligent enough in managing local affairs, but having little capacity to appreciate the importance of subjects beyond their daily sphere of action"[41] with painful consequences for their natural beauty.

The bill was considered by a committee chaired by Lyon Playfair:[49] [j] its terms of reference were (bulleting added for clarity) Manchester fielded a legal team headed by Sir Edmund Beckett QC, a leading practitioner at the parliamentary bar: they called witnesses to make the case for the scheme.

[50] Water consumption was about 22 gallons a day per person, but it was that low because Manchester had discouraged water-closets and baths in working-class housing[51][k]The waterworks did not make a profit; by Act of Parliament the total water rate could not exceed 10d per pound rental within the city; 12d in the supplied area outside the city[l] (to have equal rates would be unfair to the rate payers who stood as guarantors for very large capital expenditure) Manchester was not profiteering from its present water supply,[m] nor was it out to profit from the scheme: it would accept whatever obligation to supply areas along the aqueduct route (and/or price cap on sales outside the city) the committee saw fit to impose.

The former secretary of the Duke of Richmond's Royal Commission gave evidence of the scheme they had considered, which involved raising the level of Thirlmere 64 feet.

)[64] The brother (and heir) of the lord of the manor[p] gave evidence that the beauty of Thirlmere lay in it being more secluded than other lakes: his counsel used his examination to suggest that Manchester Corporation was buying excessive amounts of land with a view to selling off building plots should the waterworks scheme be defeated.

Edward Hull, director of the Irish section of the Geological Survey, gave evidence on the ready availability of water from the New Red Sandstone aquifer around Manchester.

[79] Playfair declined the offer of further evidence from Manchester on getting water from the Derwent catchment area, as its proponents had given no real detail, nor any notice to potential objectors: a brief comment by Bateman would suffice.

[82] Bateman's calculations were based upon aiming to fully meet demand in a dry year, but failure to do so would cause only temporary inconvenience: one might as well build a railway entirely in a tunnel to ensure the line would not be blocked by snow.

It was clear that the population of South Lancashire would continue to increase; it was absurd for counsel for the TDA to object to this as an unwarranted assumption upon which the argument that Manchester would need more water in the foreseeable future rested.

[86] The committee agreed unanimously to pass the bill in principle, provided introduction of a clause allowing for arbitration on aesthetic issues on the line of the aqueduct, and of one requiring bulk supply of water (at a fair price) to towns and local authorities demanding it, if they were near the aqueduct (with Manchester and its supply area having first call on up to 25 gallons per head of population from Thirlmere and Longdendale combined.

The President of the Local Government Board thought a Royal Commission unnecessary (much information had already been gathered and was freely available), and Howard's motion was too transparently an attempt to block the Thirlmere Bill.

Playfair also defended the committee; it had (as required by the Commons) carefully examined the regional and public interest issues which a Royal Commission was now supposedly needed to re-examine properly.

[104] In turn, Bateman (complaining "Where almost every statement is incorrect, and the conclusions, therefore, fallacious, it is difficult within any reasonable compass to deal with all") responded: the reassuring calculation reflected a recent period of trade depression and wet summers; the question was not of the average consumption over the year, but of the ability of supply and storage to meet demand in a hot and dry summer; as professional adviser to the water committee he would not have dared incurred the risk of failing to do so by delaying the start of work for so long.

[105] The waterworks committee steered a middle course; the Thirlmere scheme was not to be lost sight of, they argued in July 1884, but - in view of the current trade depression - it should not be unduly hastened.

"[107] Furthermore, the water drawn down from the reservoirs had had 'a disagreeable and most offensive odour'[108][aa] The drought broke in October; it had lasted a month longer than that of 1868, but the water supply had not had to be turned off at night; the waterworks committee thought the council could congratulate itself on this[111] but in January 1885 the committee sought,[ab] and the council (despite further argument by Alderman King) gave permission to commence the Thirlmere works.

[109] The first phase was to construct the aqueduct with a capacity of ten thousand gallons a day, and to raise the level of Thirlmere by damming up its natural exit to the north.

1893 saw another dry summer, with stocks falling to twenty-four days' supply by the start of September and that - a councillor complained - of inferior quality with 'an abundance of animal life visible to the naked eye' in tap water.

[168][169][170] The landscape remains heavily influenced by land management policies intended to protect water quality;[167]: 323 in April–May 1999 there were 282 cases of cryptosporidiosis in Liverpool and Greater Manchester and the outbreak was thought to be due to the presence of the Cryptosporidium parasite in livestock grazing in the Thirlmere catchment area.

From the south end of the lake to the dam, the reservoir completely covers the floor of a narrow steep-sided valley whose sides have extensive and predominantly coniferous forestry plantations, without dwellings or settlements.

The large blocks of non-indigenous conifers and the scar left by draw-down of the reservoir in dry periods are undoubtedly elements which detract from Thirlmere’s natural beauty.