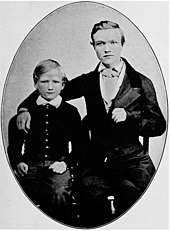

Thomas M. Carnegie

[4] His father was a master weaver, and his mother sold food in the home and sewed soles on leather boots to help provide income.

[16][17] His older brother Andrew made a good deal of money from stock investing, and in 1853 purchased their rented home on Rebecca Street.

[20][22] But the pollution from nearby factories and iron forges proved too much, and after only a few short months on Hancock Street, Andrew purchased a Victorian home for Thomas and their mother in Homewood, then a middle-class village on the edge of Pittsburgh.

When Andrew traveled to Scotland with his mother and a friend in 1862, he left Thomas in charge of his numerous business affairs (assets by that time nearing $47,860 or roughly $8.5 million in 2009 inflation-adjusted dollars).

[26] Thomas' business ventures were often pulled along in the wake of his older brother's interests, and he made his fortune in iron and steel because of Andrew.

[32] Kloman, Miller, and Phipps were soon at odds over these transactions and one another's refusal to sell out to the others, and they sought Andrew Carnegie's assistance in resolving the dispute.

Thomas, however, was deeply concerned that the Cyclops company would harm his own interests in Iron City Forge, and successfully prevailed on Andrew to merge the two firms.

)[39] Kloman and Phipps at first refused, but Thomas made an offer of all the shares in Cyclops plus an additional payment of $50,000 (a very large sum at the time).

The company struggled financially as the end of the Civil War led to sharp drops in the need for iron products, but Thomas proved to be a warm and friendly executive where his brother was cold and austere.

[43] Thomas' ability to make friends allowed the firm to receive numerous contracts and even infusions of capital when needed, and it is unlikely the company would have survived without him.

[43] Andrew wrote to Thomas extensively from Europe, constantly criticizing his business decisions, providing him with micromanaging instructions, and generally demeaning him.

[14][41][44][45] From Europe, Andrew also badgered Thomas to make improvements to their home in America, and decided to call the rapidly expanding mansion "Fairfield.

[50] Coleman provided Thomas with critical advice on how to improve the Union Iron Mills, and inside information on the coming railroad building boom.

In early 1871, William Coleman became interested in the new Bessemer process steel-making furnaces, and he traveled throughout Ohio, New York, and Pennsylvania to view these new works.

[62] Coleman invited Thomas Carnegie to join him in building the new steel works, and together they purchased 107 acres (43 ha) of land about 10 miles (16 km) east of Pittsburgh known as Braddock's Field (a historic battlefield where French and Indian forces from Fort Duquesne defeated British General Edward Braddock on July 5, 1755, in the Battle of the Monongahela).

[68] In the spring of 1872, Andrew Carnegie (while on a bond-selling trip) made a survey of Bessemer steel works in Europe and returned to the U.S. highly enthusiastic about the new project.

[70] Meanwhile, Coleman, McCandless, Scott, and Thomas Carnegie had purchased a newly platted tract in Pittsburgh, subdivided it, and sold the lots at a significant profit.

[71] Thomas was on vacation with Andrew and their mother at the upscale resort town of Cresson Springs in September 1873 when they learned of the failure of the investment bank of Jay Cooke & Company, which precipitated the Panic of 1873.

J. Edgar Thomson, president of the Pennsylvania Railroad and a mentor and close friend to many of the partners, bought many of these bonds in late 1873, helping keep the firm afloat.

[71] The company took its name from J. Edgar Thomson, who although not a large investor in the works had a superb reputation as an honest and trustworthy person (an important asset in risky financial times).

His success in this endeavor was summed up by a corporate historian this way:[76] Other historical assessments conclude Thomas had a solid grasp of the steel business and was a respected manager, even if Andrew considered him overly cautious.

[77] William Abbott, chairman of Carnegie, Phipps, & Co., considered Thomas the better businessman than Andrew, "solid, shrewd, farseeing, absolutely honest and dependable.

[80] He played cards on a weekly basis with Henry Clay Frick, Philander Knox, Andrew and Richard Mellon, and George Westinghouse.

[82] Thomas sold half his interest in Edgar Thomson Steel to his older brother in 1876 after disagreement broke out over whether to build another "Lucy furnace.

This occurred in the summer of 1876, but William P. Shinn (the second-largest stockholder in the company) complained bitterly to Andrew (traveling in Europe) that the seat should have gone to him.

[87] Andrew Carnegie decided to stop relying solely on his company's own furnaces for coke, and began seeking to buy the fuel on the open market.

Thomas and Henry Phipps had alerted Andrew to the need for a greater and steadier supply for coke for the growing steel works.

[58] In 1880, with seven children at Fairfield and the city of Pittsburgh becoming increasingly hazardous to health due to its burgeoning industry, Thomas and Lucy began seeking a winter home along the southern East Coast for their family.

[126] The will asked (but did not require) her to seek the advice of her brother-in-law Andrew and her father (who had already died eight years earlier, in 1878) in disposing of Thomas' business interests.

[126] Although Andrew advised her to sell out to him, she refused and retained ownership in businesses which led to rapid rises in her personal wealth over the next several decades.