Jefferson Davis

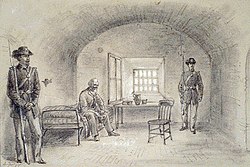

When the Confederacy was defeated in 1865, Davis was captured, arrested for alleged complicity in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, accused of treason, and imprisoned at Fort Monroe.

Less than a year later, they moved to a farm near Woodville, Mississippi, where Samuel cultivated cotton, acquired twelve slaves,[11] and built a house that Jane called Rosemont.

[20] His older brother Joseph got Davis appointed to the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1824, where he became friends with classmates Albert Sidney Johnston and Leonidas Polk.

[37] He returned to Mississippi where his brother Joseph had developed Davis Bend into Hurricane Plantation, which eventually had 1,700 acres (690 ha) of cultivated fields with over 300 slaves.

[46] Davis continued his intellectual development by reading about politics, law and economics at the large library Joseph and his wife, Eliza, maintained at Hurricane Plantation.

[137] He was chosen because of his political prominence,[138] his military reputation,[139] and his moderate approach to secession,[138] which Confederate leaders thought might persuade undecided Southerners to support their cause.

Knowing Davis desired an offensive into the North, Lee invaded Maryland,[184] but retreated back to Virginia after a bloody stalemate at Antietam in September.

Davis saw this as attempt to destroy the South by inciting its enslaved people to revolt,[197] declaring the proclamation "the most execrable measure recorded in the history of guilty man".

Davis approved, thinking that a victory in Union territory could gain recognition of Confederate independence,[202] but Lee's army was defeated at the Battle of Gettysburg in July.

[228] Davis also sent Duncan F. Kenner, the chief Confederate diplomat, on a mission to Great Britain and France, offering to gradually emancipate the enslaved people of the South for political recognition.

It left the principle of slavery intact by leaving it to the states and individual owners to decide which slaves could be used for military service,[231] but Davis's administration accepted only African Americans who had been freed by their masters as a condition of their being enlisted.

He tried to evade them, but was captured wearing a loose-sleeved cloak and covering his head with a black shawl,[242] which gave rise to depictions of him in political cartoons fleeing in women's clothes.

[270] Davis's failure to argue for needed financial reform allowed Congress to avoid unpopular economic measures,[270] such as taxing planters' property[271]—both land and slaves—that made up two-thirds of the South's wealth.

Initially, he was confined to a casemate, forced to wear fetters on his ankles, required to have guards constantly in his room, forbidden contact with his family, and given only a Bible and his prayerbook to read.

[293] After two years of imprisonment, Davis was released at Richmond on May 13, 1867, on bail of $100,000 (~$1.79 million in 2023), which was posted by prominent citizens including Horace Greeley, Cornelius Vanderbilt and Gerrit Smith.

[300] When the federal government dropped its case against him,[301] Davis left his family in England and returned to the U.S. in October 1869 to become president of the Carolina Life Insurance Company in Tennessee.

[309] Initially, the society had scapegoated political leaders like Davis for losing the war,[310] but eventually shifted the blame for defeat to the former Confederate general James Longstreet.

[314] After returning to the United States in 1874, Davis continued to explore ways to make a living, including investments in railroads, mining,[315] and manufacturing an ice-making machine.

[330] James Redpath, editor of the North American Review, encouraged him to write a series of articles for the magazine[331] and to complete his final book A Short History of the Confederate States of America.

[334] The tour was a triumph for Davis and got extensive newspaper coverage, which emphasized national unity and the South's role as a permanent part of the United States.

[355] When he spoke to Congress in April on the ratification of the Constitution,[356] he stated that the war was caused by Northerners whose desire to end slavery would destroy Southern property worth millions of dollars.

"[357] In his 1863 address to the Confederate Congress,[198] Davis denounced the Emancipation Proclamation as evidence of the North's long-standing intention to abolish slavery and doom African Americans, whom he called an inferior race, to extermination.

[360] He actively oversaw the military policy of the Confederacy and worked long hours attending to paperwork related to the organization, finance, and logistics needed to maintain the Confederate armies.

[363] He has been accused of being a poor judge of generals:[364] appointing people—such as Bragg, Pemberton, and Hood—–who failed to meet expectations,[365] overly trusting long-time friends,[366] and retaining generals—like Joseph Johnston—long after they should have been removed.

[371] It has been argued that his focus on military victory at all costs undermined the values the South was fighting for, such as states' rights[372] and slavery,[373] but provided no alternatives to replace them.

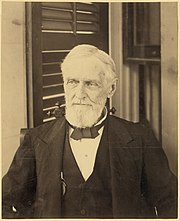

[381] Although Davis served the United States as a soldier and a war hero, a politician who sat in both houses of Congress, and a cabinet officer,[382] his legacy is mainly defined by his role as president of the Confederacy.

Some scholars argued that he was a capable leader, while acknowledging his skills were insufficient to overcome the challenges the Confederacy faced[387] and exploring how his limitations may have contributed to the war's outcome.

President Jimmy Carter described it as an act of reconciliation reuniting the people of the United States and expressing the need to establish the nation's founding principles for all.

[399] His memorials, such as the Jefferson Davis Highway, have been argued to legitimize the white supremacist, slaveholding ideology of the Confederacy,[400] and a number have been removed, including his statues at the University of Texas at Austin,[401] New Orleans,[402] Memphis, Tennessee,[403] and the Kentucky State Capitol in Frankfort.

[405] As part of its initiative to dismantle Confederate monuments, the Richmond City Council funded the removal of the statue's pedestal,[406] which was completed in February 2022, and ownership of its artifacts was given to the Black History Museum and Cultural Center of Virginia.