Tidal acceleration

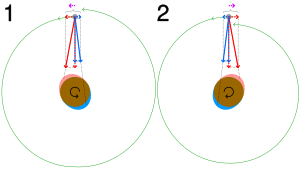

This conundrum occurs because a positive acceleration at one instant causes the satellite to loop farther outward during the next half orbit, decreasing its average speed.

Edmond Halley was the first to suggest, in 1695,[2] that the mean motion of the Moon was apparently getting faster, by comparison with ancient eclipse observations, but he gave no data.

In 1749 Richard Dunthorne confirmed Halley's suspicion after re-examining ancient records, and produced the first quantitative estimate for the size of this apparent effect:[3] a centurial rate of +10″ (arcseconds) in lunar longitude, which is a surprisingly accurate result for its time, not differing greatly from values assessed later, e.g. in 1786 by de Lalande,[4] and to compare with values from about 10″ to nearly 13″ being derived about a century later.

[5][6] Pierre-Simon Laplace produced in 1786 a theoretical analysis giving a basis on which the Moon's mean motion should accelerate in response to perturbational changes in the eccentricity of the orbit of Earth around the Sun.

Laplace's initial computation accounted for the whole effect, thus seeming to tie up the theory neatly with both modern and ancient observations.

[9] The question depended on correct analysis of the lunar motions, and received a further complication with another discovery, around the same time, that another significant long-term perturbation that had been calculated for the Moon (supposedly due to the action of Venus) was also in error, was found on re-examination to be almost negligible, and practically had to disappear from the theory.

A part of the answer was suggested independently in the 1860s by Delaunay and by William Ferrel: tidal retardation of Earth's rotation rate was lengthening the unit of time and causing a lunar acceleration that was only apparent.

Secondly, there is an apparent increase in the Moon's angular rate of orbital motion (when measured in terms of mean solar time).

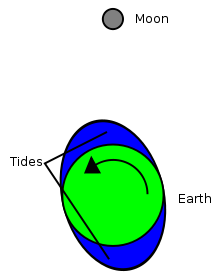

The case for the oceans is more complicated, but there is also a delay associated with the dissipation of energy since the Earth rotates at a faster rate than the Moon's orbital angular velocity.

Consequently, the line through the two bulges is tilted with respect to the Earth-Moon direction exerting torque between the Earth and the Moon.

However, the slowdown of Earth's rotation is not occurring fast enough for the rotation to lengthen to a month before other effects make this irrelevant: about 1 to 1.5 billion years from now, the continual increase of the Sun's radiation will likely cause Earth's oceans to vaporize,[15] removing the bulk of the tidal friction and acceleration.

Even without this, the slowdown to a month-long day would still not have been completed by 4.5 billion years from now when the Sun will probably evolve into a red giant and likely destroy both Earth and the Moon.

Up to a high order of approximation, mutual gravitational perturbations between major or minor planets only cause periodic variations in their orbits, that is, parameters oscillate between maximum and minimum values.

The tidal effect gives rise to a quadratic term in the equations, which leads to unbounded growth.

This geological record is consistent with these conditions 620 million years ago: the day was 21.9±0.4 hours, and there were 13.1±0.1 synodic months/year and 400±7 solar days/year.

This yields numerical values for the Moon's secular deceleration, i.e. negative acceleration, in longitude and the rate of change of the semimajor axis of the Earth–Moon ellipse.

Finally, ancient observations of solar eclipses give fairly accurate positions for the Moon at those moments.

Recent values can be obtained from the International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service (IERS).

[31] From the observed change in the Moon's orbit, the corresponding change in the length of the day can be computed (where "cy" means "century", d day, s second, ms millisecond, 10−3 s, and ns nanosecond, 10−9 s): However, from historical records over the past 2700 years the following average value is found: By twice integrating over the time, the corresponding cumulative value is a parabola having a coefficient of T2 (time in centuries squared) of (1/2) 63 s/cy2 : Opposing the tidal deceleration of Earth is a mechanism that is in fact accelerating the rotation.

From the observed change in the moment of inertia the acceleration of rotation can be computed: the average value over the historical period must have been about −0.6 ms/d/century.

[37] Moreover, this tidal effect isn't solely limited to planetary satellites; it also manifests between different components within a binary star system.

The gravitational interactions within such systems can induce tidal forces, leading to fascinating dynamics between the stars or their orbiting bodies, influencing their evolution and behavior over cosmic timescales.

In tidal deceleration (2) with the rotation reversed, the net force opposes the direction of orbit, lowering it.