Tidal force

The tidal force or tide-generating force is the difference in gravitational attraction between different points in a gravitational field, causing bodies to be pulled unevenly and as a result are being stretched towards the attraction.

Therefore tidal forces are a residual force, a secondary effect of gravity, highlighting its spatial elements, making the closer near-side more attracted than the more distant far-side.

This produces a range of tidal phenomena, such as ocean tides.

[2] Further tidal phenomena include solid-earth tides, tidal locking, breaking apart of celestial bodies and formation of ring systems within the Roche limit, and in extreme cases, spaghettification of objects.

Tidal forces have also been shown to be fundamentally related to gravitational waves.

These tidal forces cause strains on both bodies and may distort them or even, in extreme cases, break one or the other apart.

[6] The Roche limit is the distance from a planet at which tidal effects would cause an object to disintegrate because the differential force of gravity from the planet overcomes the attraction of the parts of the object for one another.

[8] The tidal force acting on an astronomical body, such as the Earth, is directly proportional to the diameter of the Earth and inversely proportional to the cube of the distance from another body producing a gravitational attraction, such as the Moon or the Sun.

Tidal action on bath tubs, swimming pools, lakes, and other small bodies of water is negligible.

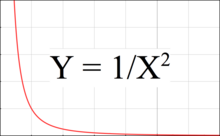

[9] Figure 3 is a graph showing how gravitational force declines with distance.

The tidal force becomes larger, when the two points are either farther apart, or when they are more to the left on the graph, meaning closer to the attracting body.

This difference is due to the way gravity weakens with distance: the Moon's closer proximity creates a steeper decline in its gravitational pull as you move across Earth (compared to the Sun's very gradual decline from its vast distance).

This steeper gradient in the Moon's pull results in a larger difference in force between the near and far sides of Earth, which is what creates the bigger tidal bulge.

Gravitational attraction is inversely proportional to the square of the distance from the source.

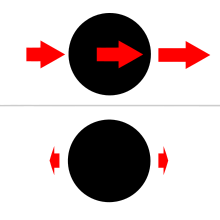

[10] In the case of an infinitesimally small elastic sphere, the effect of a tidal force is to distort the shape of the body without any change in volume.

Larger objects distort into an ovoid, and are slightly compressed, which is what happens to the Earth's oceans under the action of the Moon.

If the body is close enough to its primary, this can result in a rotation which is tidally locked to the orbital motion, as in the case of the Earth's moon.

Tidal heating produces dramatic volcanic effects on Jupiter's moon Io.

[8] Tidal forces contribute to ocean currents, which moderate global temperatures by transporting heat energy toward the poles.

It has been suggested that variations in tidal forces correlate with cool periods in the global temperature record at 6- to 10-year intervals,[14] and that harmonic beat variations in tidal forcing may contribute to millennial climate changes.

No strong link to millennial climate changes has been found to date.

[15] Tidal effects become particularly pronounced near small bodies of high mass, such as neutron stars or black holes, where they are responsible for the "spaghettification" of infalling matter.

[16] For a given (externally generated) gravitational field, the tidal acceleration at a point with respect to a body is obtained by vector subtraction of the gravitational acceleration at the center of the body (due to the given externally generated field) from the gravitational acceleration (due to the same field) at the given point.

The externally generated field is usually that produced by a perturbing third body, often the Sun or the Moon in the frequent example-cases of points on or above the Earth's surface in a geocentric reference frame.)

Tidal acceleration does not require rotation or orbiting bodies; for example, the body may be freefalling in a straight line under the influence of a gravitational field while still being influenced by (changing) tidal acceleration.

Consider now the acceleration due to the sphere of mass M experienced by a particle in the vicinity of the body of mass m. With R as the distance from the center of M to the center of m, let ∆r be the (relatively small) distance of the particle from the center of the body of mass m. For simplicity, distances are first considered only in the direction pointing towards or away from the sphere of mass M. If the body of mass m is itself a sphere of radius ∆r, then the new particle considered may be located on its surface, at a distance (R ± ∆r) from the centre of the sphere of mass M, and ∆r may be taken as positive where the particle's distance from M is greater than R. Leaving aside whatever gravitational acceleration may be experienced by the particle towards m on account of m's own mass, we have the acceleration on the particle due to gravitational force towards M as:

The first term is the gravitational acceleration due to M at the center of the reference body

In the plane perpendicular to that axis, the tidal acceleration is directed inwards (towards the center where ∆r is zero), and its magnitude is

The tidal accelerations at the surfaces of planets in the Solar System are generally very small.

[18] The solar tidal acceleration at the Earth's surface was first given by Newton in the Principia.

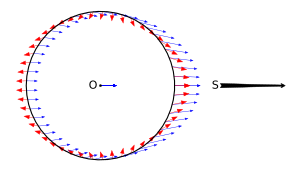

Earth's rotation accounts further for the occurrence of two high tides per day on the same location. In this figure, the Earth is the central black circle while the Moon is far off to the right. It shows both the tidal field (thick red arrows) and the gravity field (thin blue arrows) exerted on Earth's surface and center (label O) by the Moon (label S). The outward direction of the arrows on the right and left of the Earth indicates that where the Moon is at zenith or at nadir .