Freedom of speech in the United States

Possibly inspired by foul language and the widely available pornography he encountered during the American Civil War, Anthony Comstock advocated for government suppression of speech that offended Victorian morality.

City and state governments monitored newspapers, books, theater, comedy acts, and films for offensive content, and enforced laws with arrests, impoundment of materials, and fines.

To permit the continued building of our politics and culture, and to assure self-fulfillment for each individual, our people are guaranteed the right to express any thought, free from government censorship.

In Buckley v. Valeo, for instance, the Supreme Court wrote: Discussion of public issues and debate on the qualifications of candidates are integral to the operation of the system of government established by our Constitution.

In 1980, Central Hudson Gas & Electric Corp. v. Public Service Commission held that restrictions of commercial speech are subject to a four-element intermediate scrutiny.

Examples include creating or destroying an object when performed as a statement (such as flag burning in a political protest), silent marches and parades intended to convey a message, clothing bearing meaningful symbols (such as anti-war armbands), body language, messages written in code, ideas and structures embodied as computer code ("software"), mathematical and scientific formulae, and illocutionary acts that convey by implication an attitude, request, or opinion.

[27] In the 1995 decision Hurley v. Irish-American Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Group of Boston, the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed that the art of Jackson Pollock, the expressionist music of Arnold Schoenberg, and the semi-nonsense poem Jabberwocky are protected.

In each case, the courts chose to apply full First Amendment protection, but used intermediate scrutiny and upheld the content-neutral government regulations at issue (e.g. no junked cars displayed on public roads, time and place restrictions on sidewalk vendors).

Content-based restrictions "are presumptively unconstitutional regardless of the government's benign motive, content-neutral justification, or lack of animus toward the ideas contained in the regulated speech."

The Court pointed out in Snyder v. Phelps (2011) that one way to ascertain whether a restriction is content-based versus content-neutral is to consider if the speaker had delivered a different message under exactly the same circumstances: "A group of parishioners standing at the very spot where Westboro stood, holding signs that said 'God Bless America' and 'God Loves You,' would not have been subjected to liability.

The rights of free speech and assembly, while fundamental in our democratic society, still do not mean that everyone with opinions or beliefs to express may address a group at any public place and at any time.

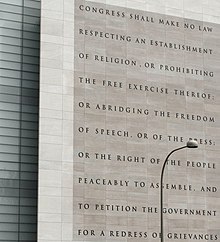

The First Amendment of the United States Constitution declares that "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

As noted in Clark v. Community for Creative Non-Violence (1984), "... [time, place, and manner] restrictions ... are valid provided that they are justified without reference to the content of the regulated speech, that they are narrowly tailored to serve a significant governmental interest, and that they leave open ample alternative channels for communication of the information.

[41] As noted in United States Postal Service v. Council of Greenburgh Civic Associations (1981), "The First Amendment does not guarantee access to property simply because it is owned or controlled by the government.

[42]" Justice Marshall in Grayned v. City of Rockford (1972), also noted something similar, saying "The crucial question is whether the manner of expression is basically compatible with the normal activity of a particular place at a particular time.

Other people, such as Justice Pierce, who delivered the opinion in The City of Chicago v. Alexander (2014), argue restrictions are only meant to defer speech, in order to limit problems that are put on society.

[35] Some examples of time, place, and manner cases include: Grayned v. Rockford (1972), Heffron v. International Society for Krishna Consciousness, Inc. (1981), Madsen v. Women's Health Center (1994), and recently Hill v. Colorado (2000).

It is speech to which all the following apply: appeals to the prurient interest, depicts or describes sexual conduct in a patently offensive way, and lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value.

Bethel School District v. Fraser (1986) supported disciplinary action against a student whose campaign speech was filled with sexual innuendo, and determined to be "indecent" but not "obscene".

Guiles v. Marineau (2006) affirmed the right of a student to wear a T-shirt mocking President George W. Bush, including allegations of alcohol and drug use.

In the 2006 index the United States fell further to 53rd of 168 countries; indeed, "relations between the media and the Bush administration sharply deteriorated" as it became suspicious of journalists who questioned the "War on Terrorism".

The zeal of federal courts which, unlike those in 33 U.S. states, refuse to recognize the media's right not to reveal its sources, even threatened journalists whose investigations did not pertain to terrorism.

The justices said that any First Amendment concerns were addressed by the provisions in the Children's Internet Protection Act that permit adults to ask librarians to disable the filters or unblock individual sites.

[81] Starting with the 1925 U.S. Supreme Court decision Gitlow v. New York, this prohibition has been incorporated to apply to state and local governments as well, based on the text of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Specifically, the issue is whether private landowners should be permitted to use the machinery of government to exclude others from engaging in free speech on their property (which means balancing the speakers' First Amendment rights against the Takings Clause).

[85] Targets have included a Massachusetts businessman who was seen in a photo apparently supporting Donald Trump,[86] female video game designers and commentators,[87] a diner where an anti-Trump employee made a negative comment to a pro-Trump customer,[88] a public relations executive who tweeted an offensive joke before boarding a plane,[89] and even victims of the 2017 Las Vegas shooting accused by anti-gun-control activists of faking the event.

Journalists such as David Brooks (commentator) and Robby Soave have criticized student activists' efforts to heckle or shut down controversial invited speakers, which they argue amounts to a heckler's veto on campus speech.

[97][98] The sociologist Musa al-Gharbi (writing for Heterodox Academy) and the legal advocate Greg Lukianoff (president of FIRE) have argued that college administrations have chilled or limited speech on campus through the partisan use of censorship and disciplinary proceedings that infringe on academic freedom.

[99][100] Other commentators such as Vox's Zack Beauchamp have disputed the claim that American college campuses are facing a "free-speech crisis," arguing that "incidents of speech by students or professors being suppressed are relatively rare," and are not directed along consistent partisan lines.

[101] Chris Quintana, writing in The Chronicle of Higher Education, argued that administration threats to academic freedom were in fact more likely to target controversial liberal professors than to be directed against conservative faculty.